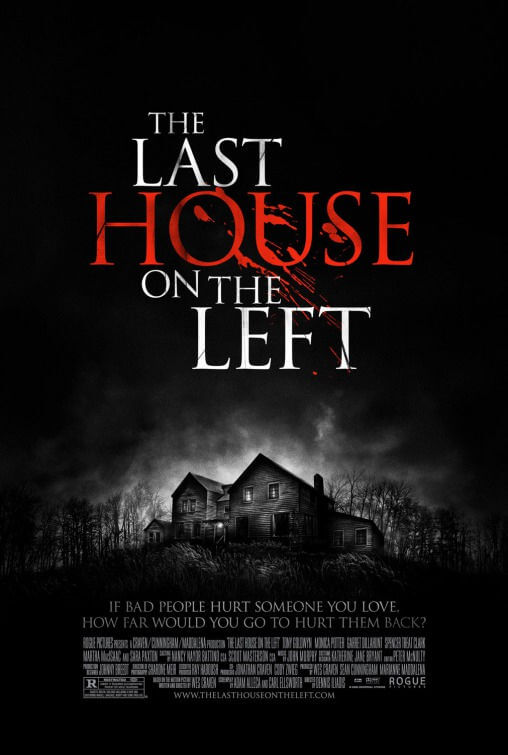

The Last House on the Left

By Brian Eggert |

Remakes are all horror movie fans seem to get anymore. Sure, maybe once or twice a year, something truly original will open—recent examples include The Mist or Teeth—but rarely does the genre support risky ventures not based on previously established material. What’s going to happen years down the road when every horror film has been remade and there’s nothing left to remake? The answer is simple: Hollywood has already begun the trend of remakes based on remakes with The Last House on the Left. Based on Wes Craven’s upsetting 1972 picture of the same name, which in turn was based on Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman’s 1960 masterpiece The Virgin Spring, this remake strays far from the original source, a medieval Swedish ballad called Töres dotter i Wänge. Suffice it to say the film concerns itself more with doing Craven justice than any Swedish poets, medieval or filmic. The setting is contemporary. The violence is bloody and graphic. And any meaning is lost on shock value.

As the story goes, sadistic criminal Krug (Garret Dillahunt) is sprung from police custody by his two perpetually laughing and snarling psycho cohorts, Sadie (Riki Lindhome) and Francis (Aaron Paul). While on the run from authorities, they bump into teenage girls Mari (Sara Paxton) and Paige (Martha MacIsaac), who are buying drugs from Krug’s confused teenage son Justin (Spencer Treat Clark). The girls are kidnapped and eventually driven into the woods, where they attempt to escape, causing a car wreck. Krug then kills one girl and rapes the other. Their transportation smashed, and the gang seeks shelter from a storm at the nearby home of John and Emma Collinwood (Tony Goldwyn and Monica Potter), who, unbeknownst to the criminals, are the parents of Mari, the rape victim. When the parents find out, though, they exact brutal retribution on the gang with whatever tools are at their disposal—be it a hammer, firearm, or microwave.

The rape scene is nearly unwatchable, and yet, it’s less explicit than the one in Craven’s version. Even when compared to the violence to follow, rape has an uncomfortable reality in its allusions, despite the scene avoiding grotesque details (unlike Craven’s). The film’s violence doesn’t shy away from typical horror movie schlock, including a pointlessly explosive finale, but still the rape is what gives us that unsettled feeling throughout. That violation also seems to justify the retaliation by the parents; what remains unfortunate is that there was no sense of guilt or conflict represented by the parents in their reaction, rendering them almost as bad as the criminals.

Helming the film is Dennis Iliadis, an inexperienced Greek filmmaker making his debut in Hollywood. Along with his cinematographer Sharone Meir (The Haunting of Molly Hartley), Iliadis creates a good-looking production not reliant on shakycam movements and unintelligible violence. Instead, they’re presenting a picture with clarity and appropriate use of color saturations to enhance the story. The viewer is given a clear understanding of space, so the horror elements of the film are all the more effective and suspenseful.

While Craven’s version sought graphic, exploitative violence because it was made when horror movies had that barrier yet to break, this film doesn’t rely too heavily on empty gore. This doesn’t mean each act of violence is necessary or meaningful. Surely the filmmakers have to dispose of Krug in a manner gristly enough to satisfy the audience’s hunger for revenge. But where Craven had boundaries to push, Iliadis has none, so he can concentrate on telling a story. The problem with both Craven and Iliadis’ remakes is that they fail to lend any poetic meaning to their structuring of the story. Krug comments on the irony that he should end up at the mercy of his victim’s parents, but that’s all the exposition offered on the narrative’s twist of fate. Bergman’s film, as you might expect, depicts brooding characters that meditate over their decisions before jumping into action, lending the more horrific scenes meaning imbued with prayer and religious doubt. The characters in both remakes simply act without considering the moral implications of their actions. However visceral a horror film this creates, the result is invariably empty.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review