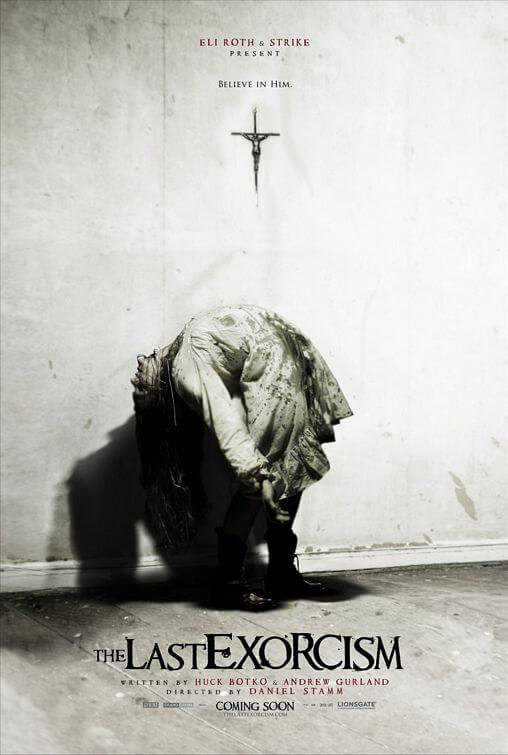

The Last Exorcism

By Brian Eggert |

A “found footage” film, by nature, almost never leaves an audience feeling satisfied. The concept behind this brand of film is that we’re seeing actual footage shot by characters in the story, in turn making the events therein seem more realistic. They’re shot on shaky digital cameras incapable of giving the audience a clear view of anything onscreen. Often these stories involve far-fetched scenarios, impossible feats of the paranormal or fantastical, which seem all the more plausible given the presentation. But then, we must realize that this footage is being presented posthumously, that someone presumably discovered the recording, and whoever made the film is long since dead. It’s the need to find out how the camera carriers died that keeps us watching.

The Last Exorcism takes the “found footage” recipe and provides a perfect example of why this horror subgenre has the worst staying power of all cinematic genres. Consider how quickly titles like The Blair Witch Project, Cloverfield, and Paranormal Activity disappeared after being quickly consumed by today’s moviegoers, all because the subgenre dictated that they end in such a way that leaves any connection to the material impossible. Like those examples, this is a one-and-done experience, not something many audiences will return to. And yet, it’s a cleverly made chiller with plenty of jolting scares to rock you out of your seat. If only the experience engaged the audience beyond the runtime.

The earliest scenes are the best. These feature a documentary crew interviewing Louisianan Reverend Cotton Marcus (Patrick Fabian), who fancies himself more a magician than a preacher. This smarmy character comes clean on camera and admits that he’s probably never believed in God, that he simply provides a service that he’s good at. During the interview, Marcus admits that he could preach about anything, even banana bread, and his parishioners would follow his cues dutifully; and sure enough, he goes out and preaches about banana bread, and his flock cheers with faith-filled hearts. Perfectly aware of the showmanship and duplicitousness involved in being a “man of the cloth”, Marcus used to perform Hollywood-worthy exorcisms for people in need. He has since stopped for fear of a child getting injured during the process. Fabian is perfect in these scenes where his character confesses, and with an enduring cockiness, he admits completely his deception of his followers.

The documentary crew follows Marcus on his “last exorcism”, a quest to expose that indeed all exorcisms are bred from hysteria, and ultimately that needy folks will believe whatever someone of religious authority tells them. Heading into the backwoods of Louisiana, they come upon the farm of sixteen-year-old Nell Sweetzer (Ashley Bell), whose father Louis (Louis Herthum) wrote to Marcus in hopes that his daughter could be released of a demonic presence inside her. Marcus places the victimized Nell in her bedroom, which he has prepared with speakers and transparent wires to create the illusion that she’s being exorcised. As Marcus proceeds to expel the demons from her body, Nell’s skeptical brother (Caleb Landry Jones) sees through his rather advanced bag of parlor tricks but realizes the charade may allow Nell to let go of whatever worldly problems are plaguing her.

Of course, Nell’s troubles are entirely other-worldly, which gives Rev. Marcus something to mull over. Some time after Marcus has been paid by Louis and the documentary crew has closed down for the night, Nell has another outburst. She becomes animalistic, lashing out in violent eruptions, and contorting her body in such a way that makes us wonder: Is Ashley Bell a contortionist or is this just some good CGI? Probably the latter, because as Nell’s behavior becomes more erratic, the filmmakers on their low-budget production probably found these tricks easier to complete in post-production. But there are also questions about Louis and his desire to isolate his children from the outside world. And what about the local townsfolk who seem friendly enough, but whose friendliness proves to be deception?

Once we realize that a moment of foreshadowing earlier in the film will play out exactly as predicted, there are really no surprises left in The Last Exorcism, except a hastily revealed plot point in the last few minutes that will have audiences hoping for a sequel, if only to clarify our “What the Hell?” questions. Director Daniel Stamm (no, Eli Roth didn’t direct; he’s the credited producer used for name-brand recognition, hence “Eli Roth Presents” on the posters) keeps the momentum going until these last few moments, ending on an omnipresent note in “found footage” movies that leaves the audience unfulfilled.

What’s surprising, aside from the lenient PG-13 rating, is that we never believe what’s going on, whereas usually with “found footage” movies—particularly The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity—there’s some buzz about the film being an authentic case of lost footage discovered and put on the silver screen. It’s that suspicion of the film’s validity that causes audiences to flock to theaters and create a pop-culture phenomenon. But there’s been no doubt from the promotional campaigns; everyone knows The Last Exorcism is phony, perhaps because the film is being “presented” by Roth, director of Cabin Fever and Hostel. It’s almost as though the film doesn’t want to try, and that hurts its chances at creating even a momentary, yet vital, misgiving in the viewer.

When film history was made with the release of The Exorcist in 1973, scores of moviegoers, even non-believers, had the bejesus scared out of them, making any filmic exorcism infantile in comparison. The Last Exorcism is no exception. The film is easy to recommend for viewers looking for almost (but not quite) 90 minutes of horror distraction. It’s well-made and does exactly what it sets out to do. But, after several “found footage” movies that structurally resemble each other, it’s hard to call the film memorable passed the first thirty minutes. If you’re looking for a frightful possession in the form of a “found footage” film, you’d be better off with [Rec], which offers the same themes in the same format, just better.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review