The Last Duel

By Brian Eggert |

In Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel, there’s a line that goes, “There is no right; there is only the power of men.” The film pummels Arthurian nobility with dialogue like this and reveals the cruel patriarchal reality beneath all that chainmail and chivalry. The heroes of yore often made grand pronouncements in the name of God, king, and country, but their world supplied a bleak existence for women, who were deemed property by their society. Screenwriters Nicole Holofcener, Matt Damon, and Ben Affleck adapted Eric Jager’s 2004 book of the same name. The story involves a rape, a lady’s accusation, her knighted husband’s pride, and a squire’s denial—and it all leads to France’s last officially sanctioned trial by combat. Hewing close to recorded history and mounted with Scott’s usual visual splendor, The Last Duel does more than supply the stage for a climactic bout between two friends turned bitter enemies. Though, the film is masterful on those terms alone. Rather, the familiar scenario becomes a relatable story for our times, reflecting how perspective and ideology overshadow the preyed upon and marginalized. Even though Scott takes us back to the strange world of fourteenth-century France, we’re still dealing with the film’s issues today.

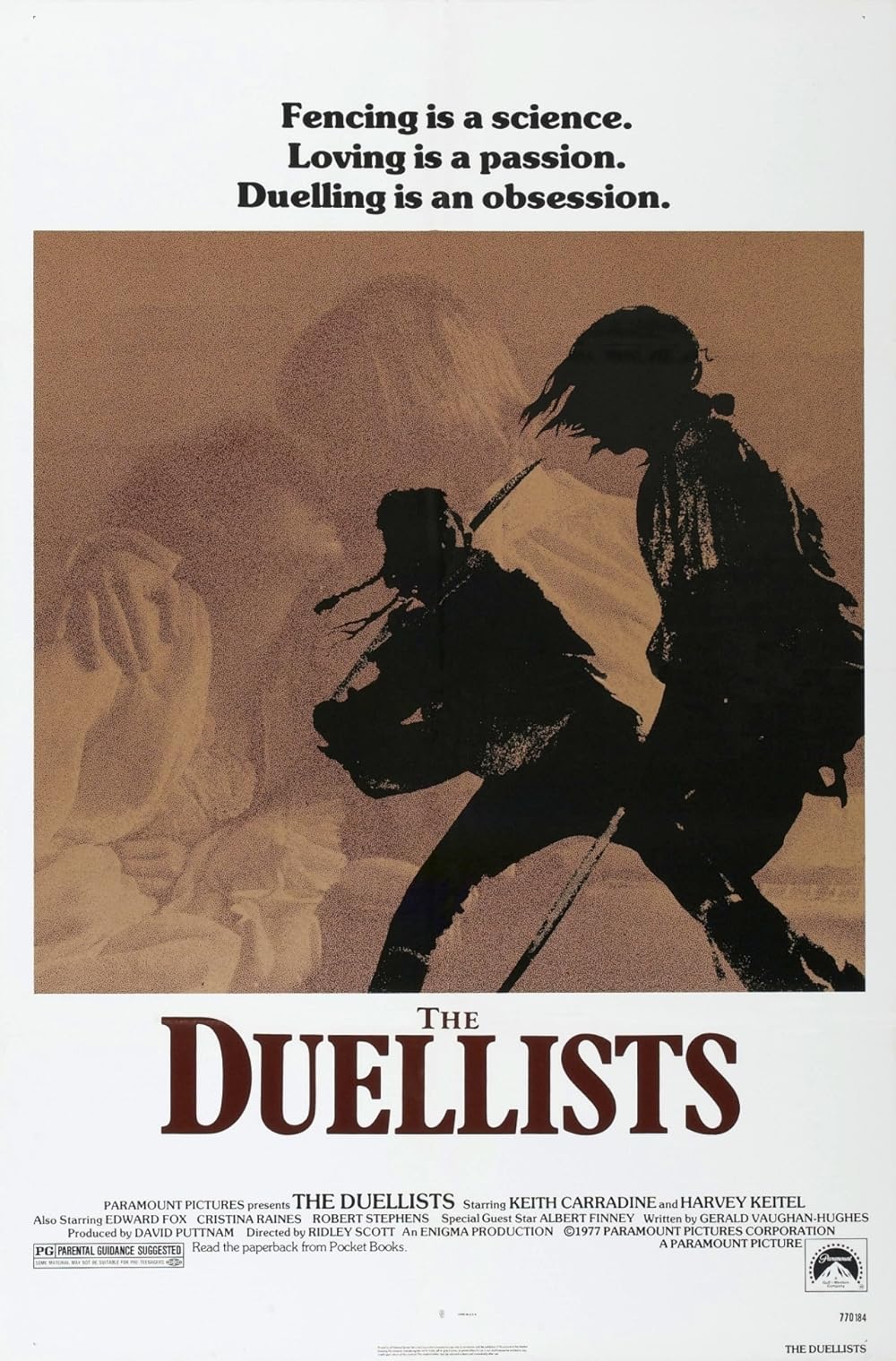

Scott is no stranger to historical drama, of course. The director launched his career with The Duellists (1977), a lavish production set during Napoleonic times, and he returned to the genre in 1992 with the misguided 1492: Conquest of Paradise. But he earned accolades galore with his multiple-Oscar-winning Gladiator (2000), which revitalized the sword and sandal epic in Hollywood. Countless imitators followed, though none quite matched his complex and sprawling study of the Crusades in Kingdom of Heaven (2005). And if audiences didn’t respond to his underrated Robin Hood (2010), a gritty update of the English legend, they were downright antagonistic toward his venture into Cecile B. Demille territory with the deary flop Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014). All of this is to say that Scott’s name is synonymous with clanging armor, flaming arrows, and muddy battlegrounds, almost as much as with aliens and artificial intelligences. And while it might be tempting to dismiss The Last Duel as another in a long line of Scott’s epics, the sharply calibrated screenplay elevates the film to one of the director’s best.

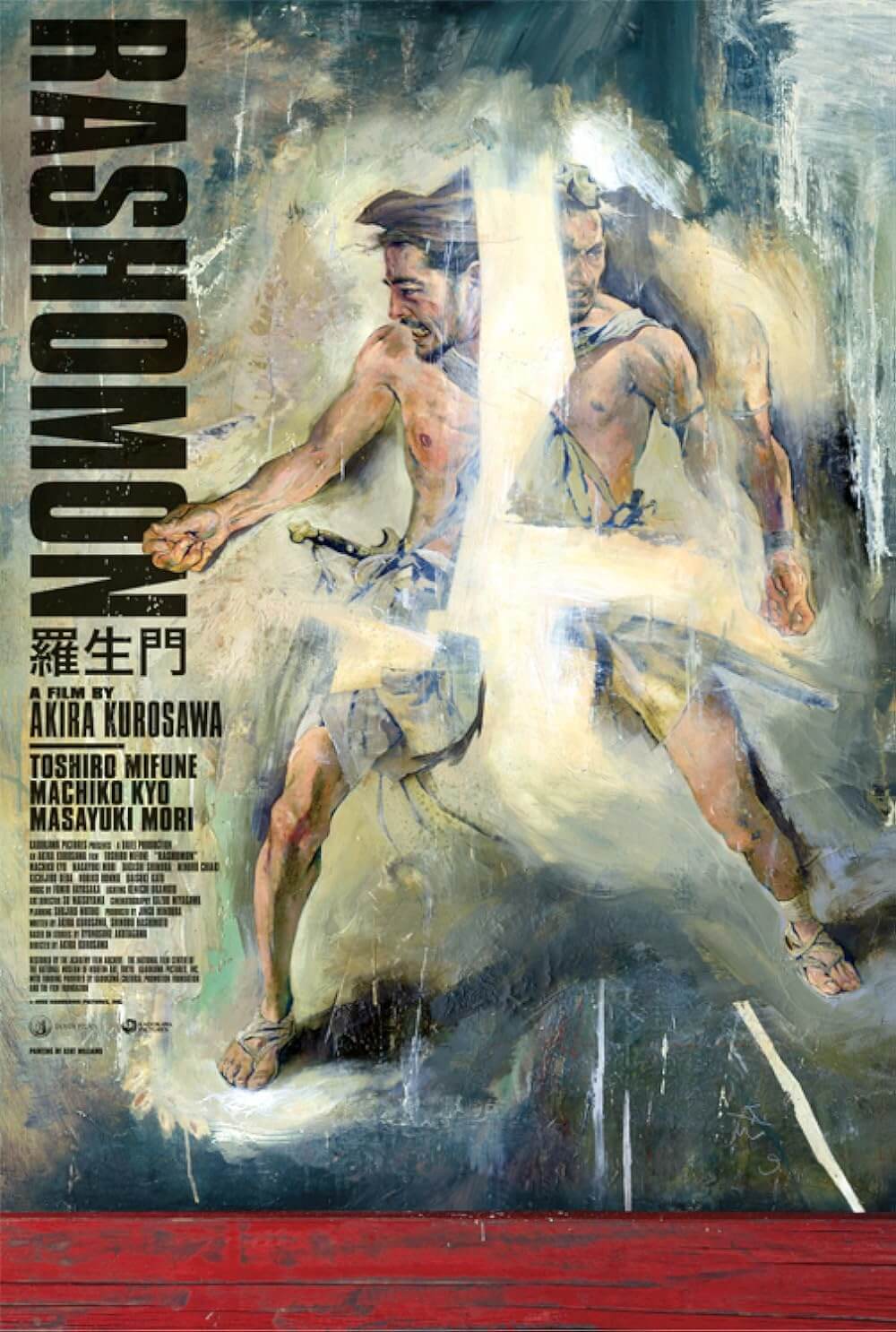

Borrowing the conceit of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), the film’s events occur over three chapters, each occupying a different character’s perspective. However, a few primary events remain consistent over the three accounts: It’s the 1380s, and squires Jacques Le Gris (Adam Driver) and Jean de Carrouges (Matt Damon) fight alongside each other in the Hundred Years’ War. After Jean makes a brave but reckless move in battle, he loses face with Count Pierre d’Alençon (Ben Affleck), the king’s influential cousin. Struggling financially, Jean enters negotiations to marry Marguerite (Jodie Comer), the daughter of a perceived traitor to the king—a detail that Jean overlooks because she comes with a sizable dowry and property. Jean also shrewdly negotiates for an additional piece of land, which Count Pierre gifts to Jacques, resulting in the first in a series of slights that the vainglorious Jean interprets as personal insults. When Jean leads a campaign in Scotland that earns his knighthood, he returns to Marguerite, who claims that Jacques raped her while Jean was away fighting. Outraged, Jean brings the matter to court, where the twerpy King Charles VI (Alex Lawther) grants his request to duel Jacques to the death, which will prove that “God has spoken” on these matters.

Borrowing the conceit of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), the film’s events occur over three chapters, each occupying a different character’s perspective. However, a few primary events remain consistent over the three accounts: It’s the 1380s, and squires Jacques Le Gris (Adam Driver) and Jean de Carrouges (Matt Damon) fight alongside each other in the Hundred Years’ War. After Jean makes a brave but reckless move in battle, he loses face with Count Pierre d’Alençon (Ben Affleck), the king’s influential cousin. Struggling financially, Jean enters negotiations to marry Marguerite (Jodie Comer), the daughter of a perceived traitor to the king—a detail that Jean overlooks because she comes with a sizable dowry and property. Jean also shrewdly negotiates for an additional piece of land, which Count Pierre gifts to Jacques, resulting in the first in a series of slights that the vainglorious Jean interprets as personal insults. When Jean leads a campaign in Scotland that earns his knighthood, he returns to Marguerite, who claims that Jacques raped her while Jean was away fighting. Outraged, Jean brings the matter to court, where the twerpy King Charles VI (Alex Lawther) grants his request to duel Jacques to the death, which will prove that “God has spoken” on these matters.

Each chapter features a title such as “The Truth According to Jean de Carrouges” and so on. The screenplay’s structure brilliantly places Jean and Jacques’ perspectives first, setting up a traditional conflict between two men. But the arrangement usurps our expectations for a conventional duel by situating the third chapter from Marguerite’s perspective. Damon and Affleck, collaborating for the first time since Good Will Hunting (1997), contributed most to the first two chapters, whereas Holofcener (Enough Said, 2013) focused on Marguerite’s story. Although many of the same events occur in each, nuanced choices by the performers and slight details diverge from earlier accounts. The only consistent performance is the mad king, who giggles with anticipation of seeing a bloody duel in every chapter. Each actor gives three slightly different performances, with minor but no less significant alternative line readings that alter their meaning and give dimension to the characters. And each chapter reveals more about how each character sees both the world and themselves. What’s fascinating about The Last Duel is how it takes all three stories to glean what really happened and understand Marguerite’s sidelined perspective in the first two chapters, similar to how Kurosawa’s film realized the truth was somewhere in-between.

The first chapter centered on Jean follows a hero type who might’ve appeared in a classical text. He’s an idealistic warrior devoted to what is morally right and what “should be,” but it becomes evident in subsequent chapters that he’s neither a politician nor particularly adept socially. However, his face shows the scars of many victorious battles. It’s Damon’s best performance in years, though much has been made of the actor’s knightly mullet—short on top, trim on the sides, and flowing in back. While the haircut is functional and historically accurate, one cannot help but see Jean as a kind of redneck stereotype by the third chapter. His devotion to duty and tradition reads as naively patriotic in later chapters, particularly after his exploits earn him a knighthood. In one scene, he proudly demands that Jacques, at the lower rank of a squire, address him as “Sir”—a moment that should embarrass Jean more than Jacques, though Jean may not realize it. By Jacques’ chapter, we see that others deem Jean temperamental, a laughing stock, even. Jean sees Jacques as villainous and vindictive and Marguerite as devoted and proud of his accomplishments. His concerns gravitate toward acquiring money, recognition, and property, a category to which Marguerite belongs. As it turns out, the traditional hero is a brutal simpleton.

The screenplay’s portrait of Jacques is entrenched in his patriarchal perspective, much like Jean’s. Educated for the monkhood but given to carnal desire, Jacques earns the favor of Pierre—who can barely remember his children’s names—through their shared appetites for literature, the Latin language, and women. Their friendship means Jacques is first in line for promotions, court appearances, and even orgies. He’s so immersed in his privilege that anything short of the world dropping to its knees for his pleasure is unimaginable. And so, Jacques sees Jean as an illiterate, aggressive brute who has nothing in common with his well-read wife. Instead, Jacques believes that he knows Marguerite, that he appreciates her, and in confusing lust with love, he believes she must love him. Jacques interprets Marguerite’s obligatory social interactions as come-ons; she even comes to him in dreams. When he eventually slithers into Jean’s castle when everyone but Marguerite is away, he declares his love. But he isn’t there to take her away from her uneducated husband, whom Jacques believes cannot possibly love her as well as he can. After he chases her upstairs to the bedroom, Jacques rapes her, attributing her repeated use of “no” to the “customary protests” of women. She moans in a borderline no-means-yes manner in his chapter, and afterward, he tells her, “We could not help ourselves.” When it comes to trial, Jacques does not believe he raped Marguerite; his society has rewarded his toxic masculinity to such an extent that he remains incapable of seeing it that way.

The screenplay’s portrait of Jacques is entrenched in his patriarchal perspective, much like Jean’s. Educated for the monkhood but given to carnal desire, Jacques earns the favor of Pierre—who can barely remember his children’s names—through their shared appetites for literature, the Latin language, and women. Their friendship means Jacques is first in line for promotions, court appearances, and even orgies. He’s so immersed in his privilege that anything short of the world dropping to its knees for his pleasure is unimaginable. And so, Jacques sees Jean as an illiterate, aggressive brute who has nothing in common with his well-read wife. Instead, Jacques believes that he knows Marguerite, that he appreciates her, and in confusing lust with love, he believes she must love him. Jacques interprets Marguerite’s obligatory social interactions as come-ons; she even comes to him in dreams. When he eventually slithers into Jean’s castle when everyone but Marguerite is away, he declares his love. But he isn’t there to take her away from her uneducated husband, whom Jacques believes cannot possibly love her as well as he can. After he chases her upstairs to the bedroom, Jacques rapes her, attributing her repeated use of “no” to the “customary protests” of women. She moans in a borderline no-means-yes manner in his chapter, and afterward, he tells her, “We could not help ourselves.” When it comes to trial, Jacques does not believe he raped Marguerite; his society has rewarded his toxic masculinity to such an extent that he remains incapable of seeing it that way.

Then comes “The Truth According to Lady Marguerite,” a chapter whose title lingers on “The Truth” in no uncertain terms. Marguerite’s perspective reframes both previous chapters, suggesting that both Jean and Jacques have failed colossally to see Marguerite. When her father arranges her marriage to Jean, she sees him as a beastly figure more concerned with how the union will help resolve his pennilessness. On their first night together, Jean mounts her, having learned everything about sensuality from animal husbandry. Indeed, Jean views her similarly to the prize-winning mare that supplies him with fresh horses to sell; Marguerite will provide him with an heir. And so, he keeps her locked away in his castle, along with his other possessions. Given her status in this society, she must be a survivor out of necessity. She’s strategic because she has to be, allowing Jean to believe that she’s proud of him, offering Jacques polite smiles when the moment calls for it. Meanwhile, she learns how to run the house when Jean is away at battle. According to her spiteful mother-in-law (Harriet Walter), who believes not complaining is a woman’s duty, even where rape is concerned, Marguerite’s independence conflicts with her place in the home. Appropriately, there’s no ambiguity when Jacques rapes her in the third chapter, and it’s difficult to watch the scene. When she tells Jean what happened, his reaction of violent doubt and incredulity remains morbidly ironic. “Can this man do nothing but evil to me?” Jean declares, viewing the incident as yet another personal slight against his manhood. And then, without concern for his wife’s wellbeing, he orders her to bed.

The Last Duel opens with a scene that teases the real-life fight to the death between Jean de Carrouges and Jacques Le Gris, which took place on December 29, 1386. The teaser suggests that the 153-minute film will gradually build to the violent showdown, resolving all conflicts. However, the audience feels less concerned about the breathless battle that ensues than the absurd bureaucracy leading up to it. When Jean insists upon an outmoded trial by combat, he also condemns Marguerite and their newborn child to a horrific death, should he lose. His priority is restoring his honor at the end of his series of petty conflicts with Jacques. “Rape is not a crime against a woman,” we’re reminded, “it is a property crime against Jean.” As a result, Marguerite must endure no end of dehumanization and ignorance during the trial that questions her accusation. This is a world in which women are servants, dowry holders, heir makers, and orgy fodder, and while on trial, even Marguerite’s sex life becomes a matter for the courts. An inquisitor drills her about whether she experiences the “little death” with her husband in bed, which, big surprise, Jean’s brutalist approach to lovemaking cannot produce. She lies and confirms that Jean brings her to orgasm, knowing that the era’s men believe conception requires pleasure and rape cannot lead to pregnancy. “This is science,” affirms the inquisitor.

Every scene of The Last Duel shows Scott’s affinity for period detail and convincing production values. We feel immersed in the time and place. Cinematographer Dariusz Wolski shot in actual castles and lends intricate texture to the convincing, period-accurate armor and dress. Although, there are some peculiarities, including the array of English and American accents accompanied by the occasional song in French. Languages aside, Scott contrasts early Paris and its sloppy village roads with Notre-Dame under construction in the backdrop, equating the church with the backward views of Medieval men when it comes to women’s rights. Then there’s Scott’s knack for rendering brutal, bloody chaos on the battlefield. A few sequences remind us that the director has mastered this, but none prove so thrilling as the final duel, which, despite its rousing effect, never overshadows our concern for Marguerite. Scott, who’s no stranger to strong women protagonists from Ellen Ripley to Thelma and Louise, reminds us that history has overlooked Lady Marguerite. The screen story is only about her insomuch that the film frames it that way (note the brilliant poster design, which underscores this theme by conveying her as negative space between two swords). Both the screenplay and direction force us to reconsider the subtle art of perspective in filmmaking—how simply being with a character allows viewers to see things from Marguerite’s eyes. Scott hasn’t felt this engaged in his material for many years.

Every scene of The Last Duel shows Scott’s affinity for period detail and convincing production values. We feel immersed in the time and place. Cinematographer Dariusz Wolski shot in actual castles and lends intricate texture to the convincing, period-accurate armor and dress. Although, there are some peculiarities, including the array of English and American accents accompanied by the occasional song in French. Languages aside, Scott contrasts early Paris and its sloppy village roads with Notre-Dame under construction in the backdrop, equating the church with the backward views of Medieval men when it comes to women’s rights. Then there’s Scott’s knack for rendering brutal, bloody chaos on the battlefield. A few sequences remind us that the director has mastered this, but none prove so thrilling as the final duel, which, despite its rousing effect, never overshadows our concern for Marguerite. Scott, who’s no stranger to strong women protagonists from Ellen Ripley to Thelma and Louise, reminds us that history has overlooked Lady Marguerite. The screen story is only about her insomuch that the film frames it that way (note the brilliant poster design, which underscores this theme by conveying her as negative space between two swords). Both the screenplay and direction force us to reconsider the subtle art of perspective in filmmaking—how simply being with a character allows viewers to see things from Marguerite’s eyes. Scott hasn’t felt this engaged in his material for many years.

The Last Duel cannot help but feel urgently necessary today. Men still seek to control women by limiting their voices and creating laws over their bodies. Even after #MeToo, some colleges today would rather punish women for speaking out about being raped than prosecute or even adequately investigate the rapists. The more things change, the more they remain the same. How appropriate that, no matter who wins in the titular duel, Marguerite’s story cannot end well. Jacques’ victory means she will be lashed and burned alive; Jean’s triumph means he will receive the glory for defending his wife’s honor. Either way, “God’s decision” will overshadow Marguerite’s conditional justice. She will never receive an apology, nor will she be recognized as someone worthy of an apology. Through its shifting perspectives, the film cuts deep into the patriarchy, allowing us to consider subjectivity from a critical vantage point. We see each side of the argument, and through them, we can better understand and identify the downfalls of patriarchal power and privilege given Marguerite’s truth. Though our culture is quick to reduce matters to black and white (“The common mind has no head for this kind of nuance,” says Pierre), there’s a subtle corruption the film exposes that goes beyond extreme examples. Toxic masculinity isn’t always about rape or obvious displays of power over women’s bodies; sometimes it’s about subtle or institutional but no less destructive behaviors. In the end, The Last Duel reminds us that Western culture hasn’t grown all that much in six hundred years.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review