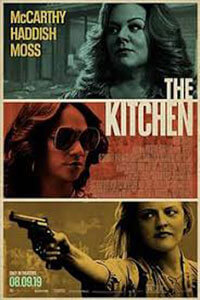

The Kitchen

By Brian Eggert |

Set on the grimy, trash-strewn streets of Hell’s Kitchen in the late 1970s, The Kitchen follows three Irish mob wives who, after their husbands get sent to Rikers Island, take over the criminal enterprise for themselves. If that sounds familiar, you might be thinking of last year’s far superior Widows, where the wives of professional thieves demonstrate that they, too, can be just as resourceful and deadly as their husbands. Both films attempt to elevate their female characters by situating them in traditionally male roles, but where Widows uses nuance, The Kitchen relies on dialogue that telegraphs its theme of empowered women. Director Andrea Berloff, writer of Straight Outta Compton, based her screenplay on the DC Vertigo graphic novel of the same name. So instead of a gritty New York drama on par with the stuff of Martin Scorsese or Sidney Lumet, the result feels like a comic-booky attempt at a crime saga. With Melissa McCarthy, Tiffany Haddish, and Elisabeth Moss in the lead roles, along with an impressive ensemble to support them, the film could have been a showcase of great performers and feminist messages. Instead, you can feel the film trying to become something it doesn’t have the patience or subtlety to be.

The action opens in January of 1978, when Jimmy (Brian d’Arcy James), Kevin (James Badge Dale), and Rob (Jeremy Bobb), the main guys in the Irish mob’s protection racket, find themselves cornered by two FBI agents (Common, E. J. Bonilla). Rob has long used his wife Claire (Moss) as a punching bag. Kevin’s wife Ruby (Haddish) has endured racist affronts from her domineering mother-in-law (Margo Martindale), the mob matriarch who whispers into the ear of the gang’s interim leader, Little Jackie (Myk Watford). And only Kathy (McCarthy) has a reasonable relationship with her husband Jimmy, free of discrimination or violence; however, she’s been limited to a homemaker despite her above-average intelligence. After their husbands are sent up for a three-year prison stint, the wives can’t find jobs, and though Little Jackie promises they’ll be “taken care of” financially, his paltry stipend is an insult. With bills to pay, the women make a bold resolution to undercut Little Jackie’s organization. But it’s not all that organized, as it turns out. The ladies quickly discover that the mob’s clientele, local businesses who pay monthly for protection, would rather work with them, as they actually follow through with the promised services. Later, they must negotiate with the head of the Italian mob (Bill Camp) in Brooklyn over their territory.

Where the film works best are its few intimate scenes. Moss is quite good as Claire, who has the fullest arc of the bunch. She transforms from a broken down, victimized woman into a violent figure who delights in the “messy” stuff. Her emergence begins when Little Jackie tries to defend his territory, and the Vietnam-vet-turned-hitman Gabriel (Domhnall Gleeson) resolves to stop him and join the alliance of working-class women. Claire and Gabriel bond over their shared skill at disposing of bodies, and Claire’s exhilaration with her newfound talent is thrilling. There’s also a doozy-of-a-scene with Ruby’s hardened mother (Sharon Washington), who admits she beat Ruby as a child to toughen her up and inspire her to become something—and Ruby has made good by becoming a mob boss. A few action scenes also deliver the occasional shock, some of them surprising and genuinely affecting, others hackneyed. When there’s a major twist in the third act, the device is absurdly handled, complete with a series of quick flashbacks to earlier scenes to show the clues the film thinks we missed (even though we didn’t). Likewise, more than once a character behaves in a way that comes out of left-field in service of the plot, making the film feel more like a string of plot points than a character-driven piece.

Watching The Kitchen, one suspects that a much longer and better film existed once, but then some executive at New Line Cinema demanded that it move faster. In its current state, this comic book story feels like a few pages are missing, while others have been organized somewhat randomly. Notice how at any given moment Berloff cuts to Common, who sits mostly wordless, watching the leads engage in criminal activities. These moments should build suspense or curiosity, as though at any moment our protagonists will meet the same fate as their husbands, but the film never makes Common or the FBI into a full-fledged presence. Elsewhere, the random editing cuts to a conspicuous rat scurrying down an alley. It might be Berloff’s nod to The Departed (2006), suggesting there’s a snitch in the bunch. Then again, it might just be the editor’s attempt at establishing the seediness of the period. The Kitchen isn’t the sort of film that constructs a tightly wound scenario or formal structure. It assumes that if the material has a wall-to-wall soundtrack with recognizable tunes from the period (the likes of Fleetwood Mac and Heart), that the audience will be too busy tapping our toes to notice how poorly constructed and written it is. And it all ends so abruptly that we’re left thinking, “That was it?”

Rather than feeling revitalized by its inclusion of women as the central characters of a crime film, The Kitchen wastes its opportunities on a familiar brand of gangster yarn. Berloff and editor Christopher Tellefsen chop together montages that show our trio of protagonists negotiating with businesses and gaining their trust, counting their money, doling out violence to those who refuse to cooperate, and attending the disco to celebrate. They’re all familiar images from this milieu, situating the film in the genre with a cinematic shorthand that seems less interested in exploring the material than rushing through obligatory touchpoints. The characters have the same surface level imperative. They don’t live and breathe, but they embody trending social justice movements, and therefore they’re marketable figureheads, played by popular actors no less, who speak in modern-day terms about feminist objectives. The actors, whose talent is mostly wasted, give bland line readings and hardly stretch their performative muscles. The film might not have felt exploitative of #MeToo if there were some substance or passion behind it, except Berloff seems to go through the motions, reducing its plot and characters to a rushed, 103-minute runtime.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review