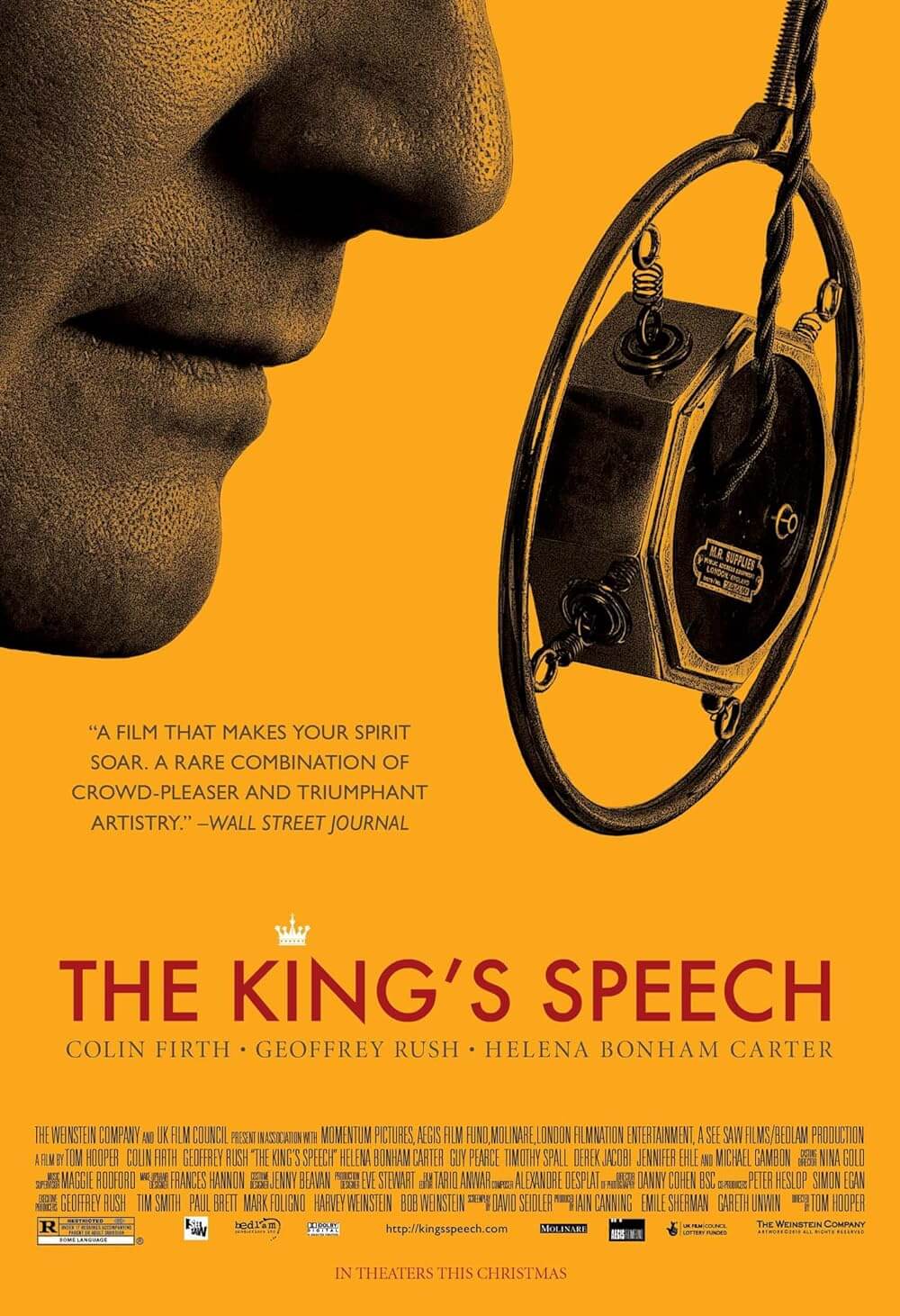

The King’s Speech

By Brian Eggert |

Long before Richard Nixon’s sweaty upper lip lost him a televised debate against John Kennedy’s good looks, it was possible for the likes of the morbidly obese William Howard Taft to be elected president. The invention of the television, and before that the radio, transformed becoming a leader into a performance art requiring not only political insight but the composed oration skills and appearance of a Hollywood actor. Since the onset of worldwide broadcasting, politicians have played their roles for the camera, and in some cases, it becomes not what they’re saying but how well and how good they look saying it.

Telling a story about the beginning of this transition, from leaders who exist by authority to those who must be showmen, The King’s Speech is deceptive in its simplicity. Though heavy with political and historical implications, the narrative is reduced to a human drama with broad appeal. The result could be compared to a sports movie, in that the film involves one man’s perseverance and ultimate triumph over his failings, and employs all the typical formulas in the process. Indeed, it comes from Tom Hooper, director of the British soccer film The Damned United, and both are stories about big goals saddled by intrapersonal conflicts.

The story begins in 1925, and the future of the British Royal Family remains in question. The failing health of King George V (Michael Gambon) leaves the eldest son, Prince Edward (Guy Pearce), expected to ascend to the throne. But Edward couldn’t be less interested in such matters. Nevertheless, this leaves Prince Albert (Colin Firth), the Duke of York, who has no desire to become King, in the clear. During his few public speeches, Albert’s embarrassing stammer crippled any desire to advance toward Buckingham Palace. His wife Elizabeth (Helena Bonham Carter) has sought out every speech coach of credible value to help her husband, but none have succeeded in eliminating the stutter.

Enter Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush), an Australian speech therapist known for unorthodox, if unknown methods. As a last-ditch effort, Elizabeth employs Logue, who insists on being equals with his clients, royalty or otherwise. He calls the prince by his family name, “Bertie”, and speaks to him no differently than he would anyone else—insisting that Bertie speak about his past to reveal the root of the impediment, which was brought about by some psychological obstacle. That obstacle becomes apparent in the mocking disdain of Bertie’s father and brother, the source of his inferiority complex. But as Edward decides to abandon the throne to marry the twice-divorced Wallis Simpson (Eve Best), Bertie must assume the crown and address his empire in the first of many wartime speeches.

What emerges is an unassuming costume piece that manages to dwarf the concerns of an empire with a stirring and funny human drama about friendship and personal bravery. The social expanse between Bertie and Logue disappears between them over time, as Logue becomes something Bertie has never had, an honest friend. It seems “feel-good” when put that way, but the film’s effortlessness is its best attribute. Hooper forgoes the need for ambitious royal scenery by simplifying the production to functional, modest interiors and carefully framed close-ups. Alexander Desplat’s score feels classical, but not extravagant. This isn’t a film about majesty, but about keeping in touch with humanity in the face of royal decorum. Several scenes involve Logue demystifying royal traditions to make Bertie comfortable with them. When Bertie finds Logue sitting on a throne, he tells him “You can’t sit there.” “Why not,” the self-assured Logue replies. “It’s just a chair.”

Hooper’s polish here is only matched by his exquisite casting, which represents one of the best ensembles in recent memory. Gambon and Pearce exhibit the kind of heart-stripped figures you’d expect to come from a monarchy. Bonham Carter displays impressive sympathy, despite playing mostly villainess roles in recent years. Derek Jacobi, who played the stammering protagonist in I, Claudius, makes a notably unsympathetic Archbishop Lang. Claire Bloom is regal as the king’s proud mother, Queen Mary. Timothy Spall’s rendition of Winston Churchill has one crossing their fingers for a future biopic. And Jennifer Ehle, who starred alongside Firth in the BBC miniseries Pride and Prejudice, captures the surprise of Myrtle Logue when she finds the king and queen in her home for tea.

Of course, the entire cast stands in the shadow of their two masterful leading men, who together make The King’s Speech a sort of buddy movie. Firth deserves the many accolades he’s received for his performance after inhabiting his character so fully that he simply becomes Bertie. Much of his role depends on the pronunciation of Bertie’s stammer, which, to someone with an ingrained fear of public speaking, feels tangible in its authenticity. But it’s more than prominent W’s and getting his throat caught up on certain words; Firth puts himself into the role in such a way that few actors can. At once, he exudes profound vulnerability and courage, while also communicating an emotionally wounded figure that we respect. Yet, setting up Bertie’s every breakthrough is Rush, whose hilarious, frank approach to his client brings the film’s most delightful moments. Like his costar, Rush shows both weakness and strength, resulting in transcendent humanity. Both men deserve all the awards that are no doubt coming to them.

Though criminally rated “R” in yet another nonsensical decision by the MPAA, The King’s Speech should be seen by everyone. The rating refers to multiple uses of the F-word that are never employed nastily, but rather within the context of Logue’s therapy. After all, it’s just a word; don’t let a few “fucks” prevent you or your teenagers from seeing one of the best films in the quite dull cinema year of 2010. This is a resonant picture about a complex friendship and personal conviction that’s as touching as it is inspiring, and it does all this without feeling cliché or typical. With its sense of personal drama inside a grander, global scope, Hooper’s film works in every way that it should and will leave audiences wanting to cheer for its warm heart.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review