Reader's Choice

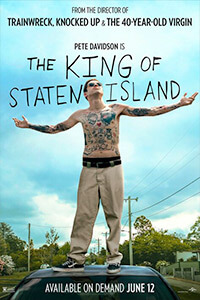

The King of Staten Island

By Brian Eggert |

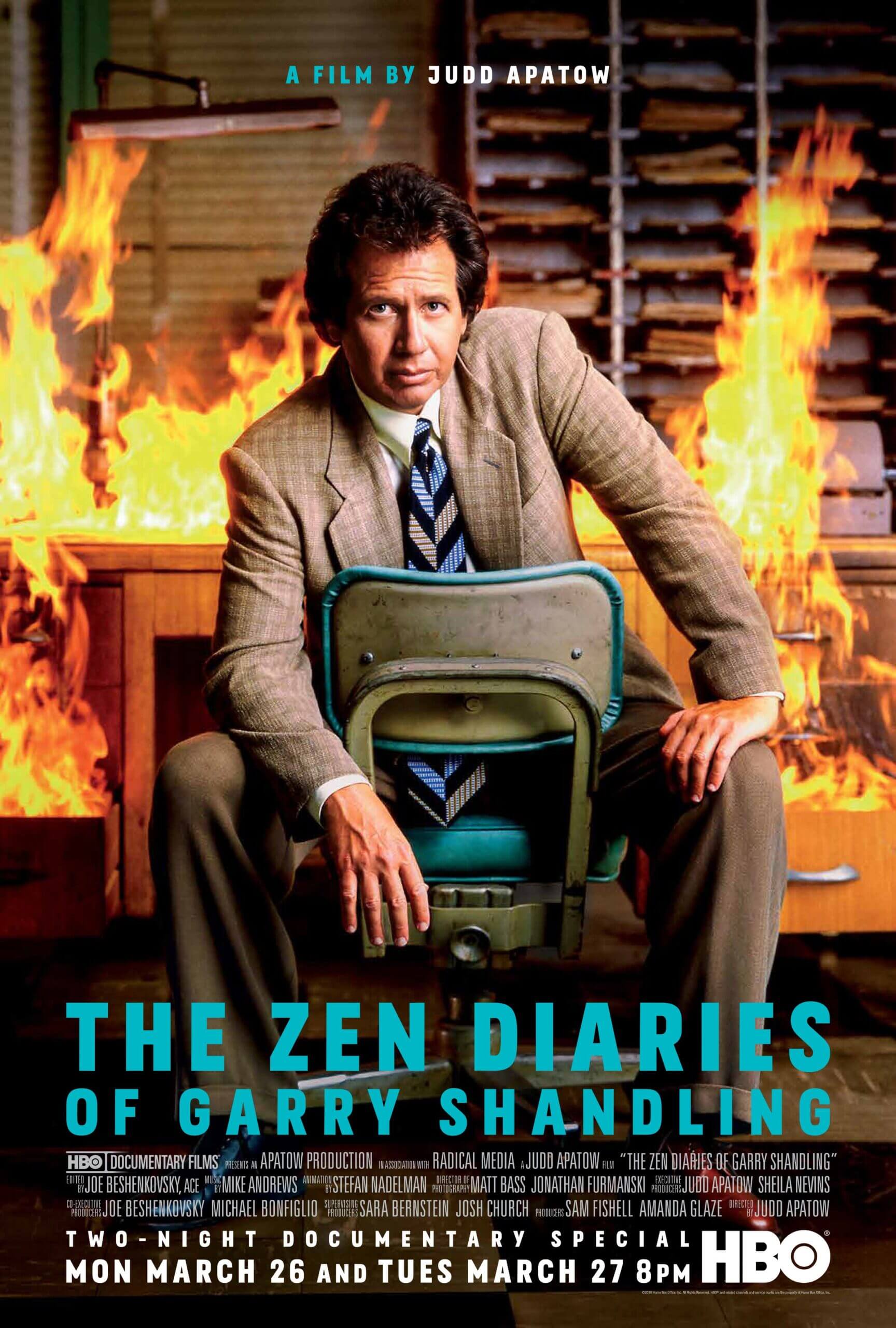

If there’s a recurring theme in every Judd Apatow comedy, it’s arrested development. More often than not, his movies involve man-children whose juvenile friendships, usually with other man-children, define them. This is true of his 2005 directorial debut, The 40-Year-Old Virgin, and every subsequent comedy bearing Apatow’s signature (Knocked Up, Funny People, This Is 40). He took a slight detour in a story about an immature woman in Trainwreck, featuring Amy Schumer, but the same basic principle applies. Though he finds a great deal of humor exploring the complex and often self-destructive behavior of his characters, he also acknowledges that their lives are unhealthy and require change, lending an emotional anchor to the material. Inevitably, each of his protagonists is forced to finally mature and commit to some aspect of adulthood they have long avoided: finally having sex, becoming a responsible parent, committing to a career or a relationship. Apatow’s latest, The King of Staten Island, returns to this thematic well for a semi-autobiographical movie about SNL player Pete Davidson, who has made a career out of saying whatever comes to his mind.

Apatow is also known for creating awareness about unsung comic personalities, giving them a cinematic bar mitzvah of sorts. He made leading men out of Steve Carell and Seth Rogen, gave Schumer her big-screen break, and endeared us to Leslie Mann. In each case, he takes what works best about a comedian’s persona and gives it ample room to breathe on-screen. His approach depends on improvisation, working through scenes and setups in which his cast can ad-lib moments, many of which end up in the gag reel or discarded into the digital trash can. Then again, Apatow’s final cuts often feel as though he found certain inessential scenes too precious to remove. His detractors often cite the inflated runtimes of his movies, which have been known to extend over the two-hour mark. But from another point of view, he’s making hangout movies that give his audience the chance to recognize what he sees as a promising talent. And when you’re hanging out with good friends, the hours disappear and time has no meaning. The same is true of The King of Staten Island, which opens, as many Apatow movies do, with a bunch of friends smoking weed and riffing.

The screenplay by Apatow, Davidson, and Dave Sirus so closely resembles Davidson’s real off-screen life that it’s anyone’s guess why his character is named Scott Carlin. Like Davidson, Scott continues to live with his mother in his mid-20s; he also suffers from depression and covers his body in tattoos. Scott’s FDNY father died when he was very young—unlike his fictional counterpart, Davidson’s dad was killed on 9/11 trying to save lives in the World Trade Center—and he uses that trauma to justify his lumpish behavior. He has a neat-if-impractical tattoo restaurant idea called “Ruby Tattoosdays,” but nothing will come of that. He’d prefer to use his friends (Moisés Arias, Ricky Velez, Lou Wilson) as canvases for his hilariously amateurish ink. At once scuzzy and genuine, Scott has Davidson’s confessional appeal—he’s willing to call out his own downfalls, and those of others, without a social filter. It can be hilarious and disarming, but speaking on impulse has a quick way of ruining relationships.

Scott lives in Staten Island, obviously, with his nurse mom Margie (Marisa Tomei) and sister Claire (Maude Apatow). Stuck in autopilot, he seems comfortable hanging out with friends and having casual sex with Kelsey (Bel Powley), who wants labels and commitment—everything he’s trying to avoid. All at once, his cozy-lazy routine comes crashing down. Claire goes off to college, leaving mom to look elsewhere for friendship. She fails to bond with Scott, who refuses to watch Game of Thrones with her. Instead, she starts dating a firefighter, Ray (Bill Burr, behind a gross mustache and shaved head), the father of a 9-year-old boy whom Scott tattoos in a riotous scene. The fact that the first man Scott’s mother dates after the death of his father is another firefighter doesn’t sit well with Scott. And before long, Margie expects her son to move out, get a job, and generally take on the responsibilities of adulthood that prove more difficult for someone in Scott’s condition. Rather than accept the challenge, he flirts with homelessness and criminality before coming to his senses.

Although The King of Staten Island has Apatow’s usual hangout atmosphere early on, the movie teeters into pure dramatic territory given the severity of Scott’s problems, especially in the second half when he and Ray begin to bond. The detour into Scott spending time at Ray’s firehouse, cleaning toilets and riding along to actual calls, feels tender, especially with a fatherly Steve Buscemi playing the resident chief. Scott also begins a morning routine of walking Ray’s two small children to and from school, and the frank discussions between the three kids, one of them oversized, prove endearing. As a millennial, his states of emotional fragility and narcissism might be expected clichés. But Ray, too, has some growing up to do. When he finds himself on the outs with Margie, Ray must confront his own failings as a divorcee, gambler, and immature man. Apatow acknowledges that everyone moves through life at their own pace, despite what our society says is appropriate or normal.

The darker undercurrent in the movie is evidenced in the first scene, where Scott almost submits to the death drive on the Staten Island Expressway. It sets the tone for what might be called a “dramedy,” though the quiet laughs throughout are more consistent than that label suggests. Perhaps these severe flourishes are why Apatow sought Robert Elswit (who shot most of Paul Thomas Anderson’s textured work) to shoot his movie—and deliver visuals that never call attention to themselves, though they’re capably handled by the overqualified cinematographer. Still, even at 136 minutes, The King of Staten Island doesn’t overstay its welcome, even as it meanders and finds itself distracted by smaller moments of Scott’s life. Having had little exposure to Davidson’s SNL presence (outside of the occasional headline) or stand-up routine, it was nonetheless a pleasure to hang out with him in a manner that fans of other Apatow comedies will enjoy.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review