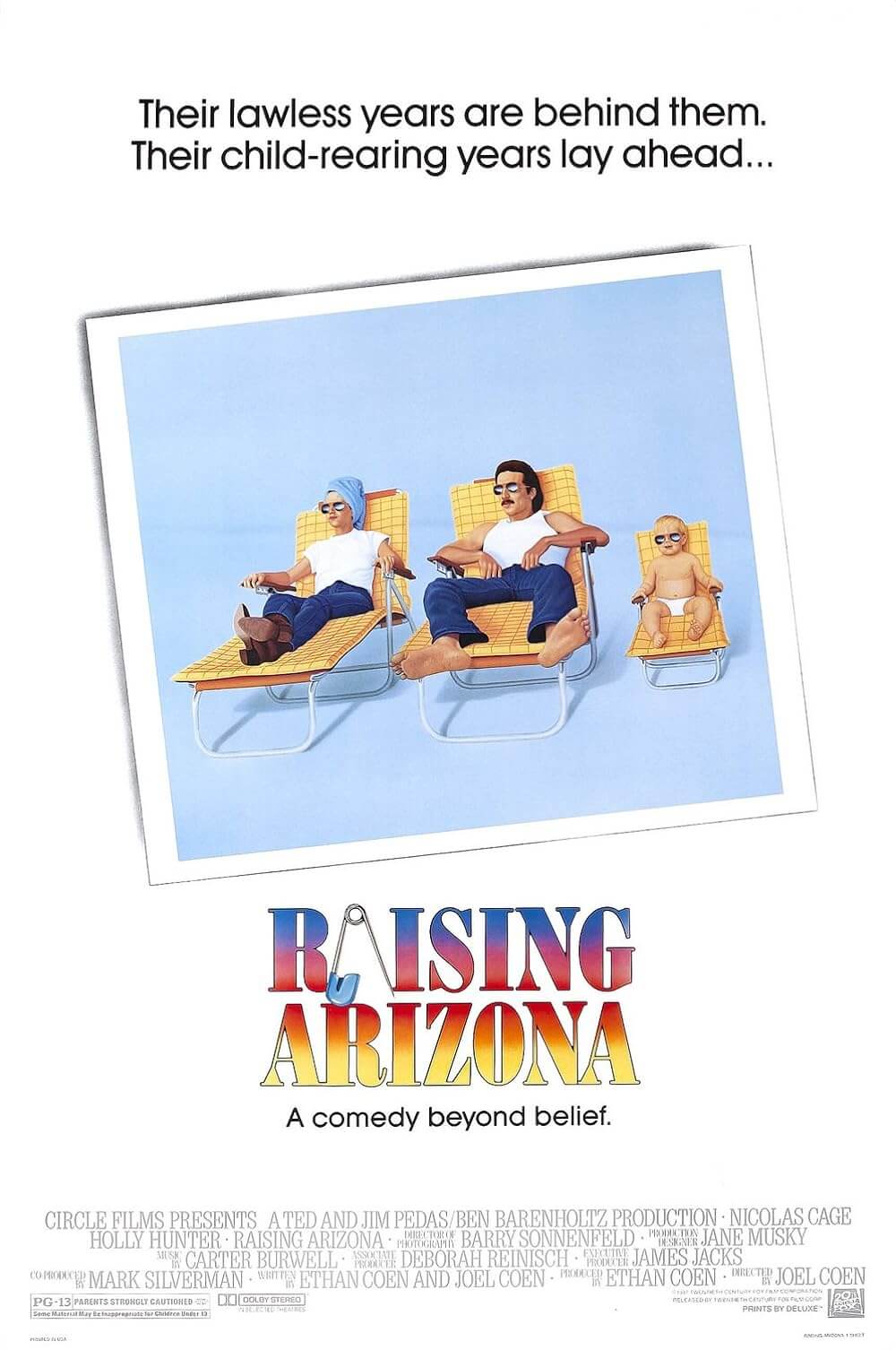

The Killer Inside Me

By Brian Eggert |

Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me, an adaptation of author Jim Thompson’s eerie pulp novel from 1952, takes a fearless plunge into murderous material and remains unforgiving to the last moment. In the same realm and tone of Mary Harron’s American Psycho, the often uncomfortable experience also happens to be an extremely well-made and acted film, featuring one of the year’s best performances in star Casey Affleck. Although controversial and not for the timid, this unnerving, macabre tale of a psycho killer has its rewards for the right audience.

Set in West Texas in the 1950s, the film opens from the perspective of Lou Ford (Affleck), a soft-spoken and polite deputy sheriff who doesn’t bother carrying a gun, because his hometown, the sleepy Central City, has such little crime. Tasked to run a prostitute named Joyce (Jessica Alba) out of town, he arrives at her doorstep and finds himself in the company of a woman who shares his aggressive tastes in the bedroom. Her embrace of Ford’s darker passions unleashes a wealth of monstrous appetites and a self-destructive murdering streak. Meanwhile, Ford keeps a respectable girlfriend in Amy (Kate Hudson), who doesn’t suspect her beau’s morbid desires. Indeed, no one in town—not the trusting sheriff (Tom Bowers), the know-all union man (Elias Koteas), nor anyone else—suspects Ford is capable of unspeakable acts of violence.

Shouldering a tragic past, compounded by confusion between pain and pleasure, Ford snaps one day and resolves to release whatever impulses dwell inside him. He begins small, by burning a cigar on the palm of a drunken hobo. But once bodies begin to pile up, his modest cover is no longer enough to keep those around him from suspecting Ford was involved somehow. The nosy district attorney (Simon Baker) simply won’t let up, and Amy can tell that Ford is in some kind of trouble, yet she loves him unconditionally. And despite the pressures of being a suspect, Ford remains self-assured, complete with the airs of an old-timey Texan gentleman, ever clean-cut in his modest dress and wide-brim Stetson.

Much has been made of the film’s violence against women, which is brutal and at times unwatchable, particularly during a scene where Ford beats Joyce about the face until he believes her dead. Thompson’s book compared this moment to “pounding a pumpkin,” and it’s just as awful to witness as your imagination might guess. Yet Winterbottom carefully avoids glorifying the violence and instead points out the sickening nature of the brutality. Although, the moral meaning behind the overall film, if one exists, remains uncertain. Most importantly, however, the plot does not suggest that these acts occur as a result of misogyny, nor does it suggest that Ford harbors any hatred toward women. Rather, these incidents are moments carefully calculated, with as much brains as this small-town psychotic can muster, to achieve something within the plot (e.g. to frame someone else for his murders).

Once you get passed the violence, there are strong performances to savor. Affleck offers another embodiment of a role on par with his turns in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and Gone Baby Gone. He’s so unassuming and coolly vicious that the audience remains equal parts fascinated and fearful of their untraditional protagonist. Alba and Hudson put aside their fluff movie temperaments for some actual performances for a change. And Koteas is slyly menacing as the watchful eye who puts together the elaborate (contrived even) string of lies that Ford has buried himself with.

Winterbottom, whose résumé includes a mixed bag of genres and styles (including the political melodrama A Mighty Heart, the rock biopic 24 Hour Party People, and the hilarious mockumentary Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story), succeeds in presenting an eerily persistent calm to the picture, but without much style. Thompson’s text is begging for an ironic or auteurist adaptation, but Winterbottom proceeds with Marcel Zyskind’s understated cinematography, unfussy editing, and lackadaisical pace. This approach aligns with Affleck’s quietly horrifying onscreen persona and forces the viewer to fully confront the character of Ford, but it scarcely serves the effect of the overall film, which seems to cry out for a more stylish interpretation—something in the way of Brian De Palma. As is, The Killer Inside Me works in a controlled way, always with something visceral under the surface, but one can’t help but imagine how a more inventive and dynamic version would have left a better impression.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review