The Killer

By Brian Eggert |

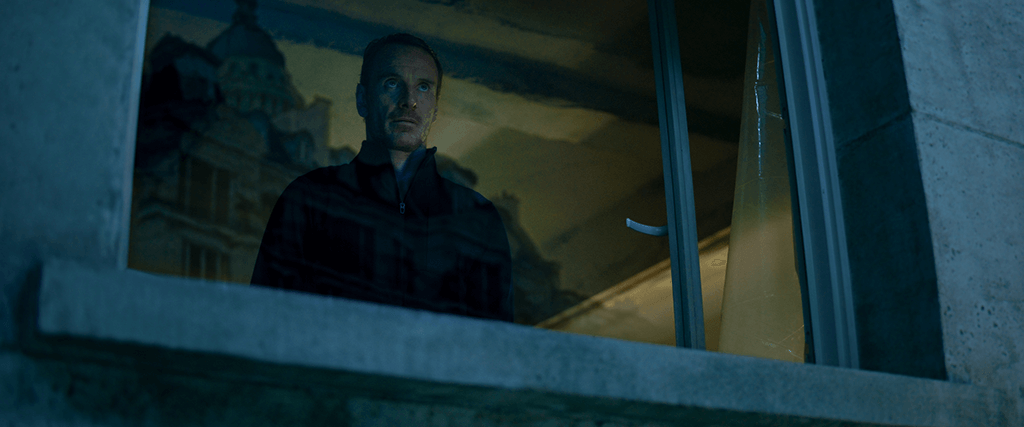

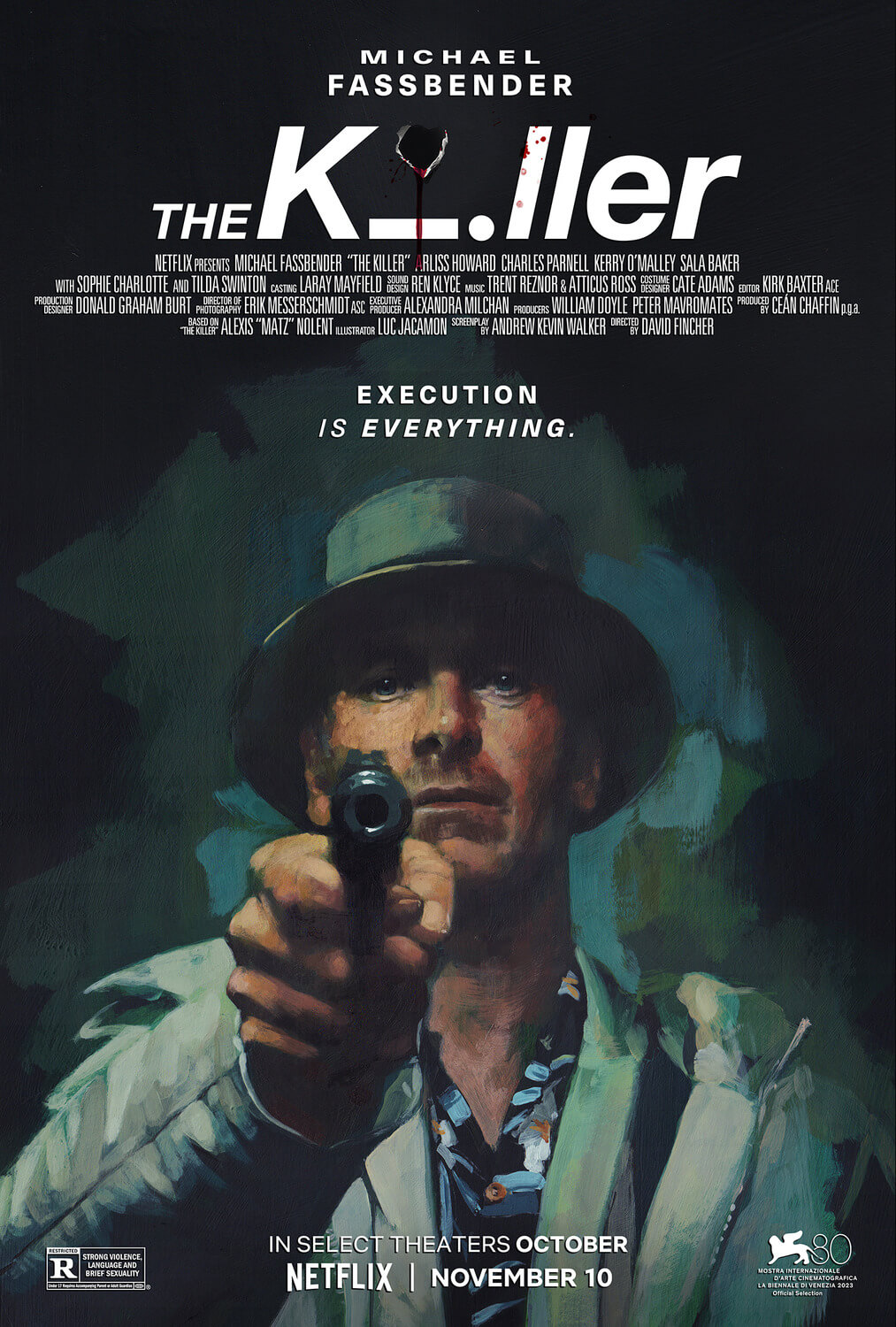

Sleek, sharp as a knife, and unrelentingly ascetic, David Fincher’s The Killer initially seems like a cold, process-oriented portrait of a hitman. And perhaps that’s all it is. But it might also be Fincher painting a self-portrait in the form of a hired gun whose personal doctrine and best-laid plans occasionally go awry. Like the film’s unnamed assassin, played by Michael Fassbender, Fincher is notoriously fastidious, demanding perfection through entrenched preparation, long shoots, and multiple takes, often resulting in formal brilliance. He has a vision and will go to extreme lengths to execute it, even if it means a grueling experience for his cast and crew. Similarly, Fassbender’s character lives by fixed tenets that have kept him alive and flourishing in his work—he is an expert killer, which has earned him millions. Even within their calculating approaches, however, mistakes will be made. They’re only human, after all. Fincher seems to admit as much with his latest, evidenced as Fassbender listens only to the wounded outpourings of The Smiths, marked by the refrain from “How Soon Is Now?” echoing, “I am human and I need to be loved, just like everybody else does.” Beneath the chilly exterior is a film about a man trying desperately to maintain control and follow his self-prescribed precepts, even though the world may refuse to cooperate.

Adapted by the director’s longtime collaborator, Andrew Kevin Walker (Se7en, 1995), from the French-language graphic novel of the same name—written by Alexis “Matz” Nolent and illustrated by Luc Jacamon—the film aligns with Fincher’s other austere, meticulously crafted thrillers. After his last film, 2020’s Mank, a thorny biographical drama steeped in hotly debated Hollywood history, The Killer feels like a palate cleanser. It’s as though the director needed to crank out another in his many efficient genre pieces to reset. The film belongs in a conversation with Fincher’s The Game (1997), Panic Room (2002), and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011)—features that play as pure, well-executed crime stories. But apart from his particular brand of aesthetic perfectionism, he imbues each with sophisticated commentary, here imbedded into an extreme form-follows-function method of storytelling. In The Killer’s case, Fincher’s commentary is sly, making it the sort of film, like Fincher’s Fight Club (1999), that will probably send the wrong message to those who take the proceedings at face value.

The Killer follows its main character closely. Though Tilda Swinton, Arliss Howard, and Charles Parnell each have memorable, contained scenes opposite Fassbender, the lead actor commands what at times feels like a one-man show. Despite Fassbender’s outwardly cool, composed façade, Fincher suggests the film is more than simply a familiar hitman scenario elevated by his particular directorial style—regardless of the “Execution is Everything” tagline. The character’s omnipresent narration continuously spouts an inner monologue, often citing scientific metrics to reinforce his worldview, such as his choice to consume protein from McDonald’s, sans the muffin from an Egg McMuffin. With an air of superiority, he mocks people who play Wordle or have faith in humanity’s goodness (“Based on what?” he asks rhetorically). And he almost seems self-deprecating when he remarks, “I’m no genius” and “I’m not exceptional.” He’s the sort of character who doesn’t admit that he likes sleep, but instead observes, “Of the many lies told by the American military industrial complex, my favorite is that sleep deprivation isn’t torture.”

The Killer follows its main character closely. Though Tilda Swinton, Arliss Howard, and Charles Parnell each have memorable, contained scenes opposite Fassbender, the lead actor commands what at times feels like a one-man show. Despite Fassbender’s outwardly cool, composed façade, Fincher suggests the film is more than simply a familiar hitman scenario elevated by his particular directorial style—regardless of the “Execution is Everything” tagline. The character’s omnipresent narration continuously spouts an inner monologue, often citing scientific metrics to reinforce his worldview, such as his choice to consume protein from McDonald’s, sans the muffin from an Egg McMuffin. With an air of superiority, he mocks people who play Wordle or have faith in humanity’s goodness (“Based on what?” he asks rhetorically). And he almost seems self-deprecating when he remarks, “I’m no genius” and “I’m not exceptional.” He’s the sort of character who doesn’t admit that he likes sleep, but instead observes, “Of the many lies told by the American military industrial complex, my favorite is that sleep deprivation isn’t torture.”

The Killer opens in Paris after a propulsive opening credits sequence that races across the screen—likely designed to appease viewers with short attention spans watching on Netflix (the film’s home after its short theatrical run), who are known to check out after two minutes if not instantly entertained. The protagonist spends days waiting in an empty WeWork office for his latest mark to arrive in an apartment across the street. When they do, Fassbender’s character botches his objective. “This… This is new,” he remarks in his intoned voiceover, wholly unfamiliar with everything not going according to plan. Despite following a rigid dogma that has kept him alive, his failure proves his rules are fallible. But whenever he’s prompted to act, he remains committed to and repeats his mantra in his head: “Stick to the plan. Anticipate, don’t improvise. Fight only the battle you’re paid to fight. Empathy is weakness.” He knows no other way, even if it occasionally betrays him, even if he breaks those rules consistently for the remainder of the film. But he’s also self-aware enough to acknowledge his hypocrisy with a question: “How’s ‘I don’t give a fuck’ going?”

Fassbender’s character subsists on faulty perfectionism, recalling Alain Delon’s character in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967)—who defines every action through the lens of the Bushido Code. Though both hitmen live according to a trenchant code, it doesn’t prevent them from breaking their rules or making one miscalculation after another (and it didn’t turn out well for Delon’s character). Fassbender, who hasn’t appeared in a film since 2019 (he’s been pursuing a career as a race car driver), has been perfectly cast given his severe presence. His wiry frame and unkind face have the unflinching disposition of a psychopath, while his voice dryly dispenses amusing takes on Storage Wars and Airbnb. Compared to Melville’s utterly self-serious film, Fincher’s is a quiet riot. Fassbender’s character may drone through his narration and perform actions with mastered skill, but the contrast between his actions and inner voice often supplies a stark irony and constant source of humor—not laugh-out-loud humor, mind you, but the sort that prompts your brain to acknowledge this is funny.

Expertly made, The Killer finds Fincher and his editor Kirk Baxter trimming every piece of fat from the 118-minute runtime, creating a proficient machine. The cutting is logical and linear, allocating time for significant and fastidious details while assembling the protagonist’s journey of escape and revenge from Paris to the Dominican Republic, then to Florida, New Orleans, New York, and Chicago. Working once again with cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, who shot Mank and much of Fincher’s Netflix series Mindhunter, Fincher delivers a characteristically dark film. One brutal hand-to-hand combat sequence in the middle, though wonderfully choreographed, may prove unintelligible on a lesser multiplex projector or subpar home theater system, once again raising the question of whether filmmakers should be accounting for suboptimal displays in their creative choices (they should not). All the while, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross supply Fincher with another terrific score, an electronic force, often disorienting in its crackling quality that sounds like stacking dried bones.

Expertly made, The Killer finds Fincher and his editor Kirk Baxter trimming every piece of fat from the 118-minute runtime, creating a proficient machine. The cutting is logical and linear, allocating time for significant and fastidious details while assembling the protagonist’s journey of escape and revenge from Paris to the Dominican Republic, then to Florida, New Orleans, New York, and Chicago. Working once again with cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, who shot Mank and much of Fincher’s Netflix series Mindhunter, Fincher delivers a characteristically dark film. One brutal hand-to-hand combat sequence in the middle, though wonderfully choreographed, may prove unintelligible on a lesser multiplex projector or subpar home theater system, once again raising the question of whether filmmakers should be accounting for suboptimal displays in their creative choices (they should not). All the while, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross supply Fincher with another terrific score, an electronic force, often disorienting in its crackling quality that sounds like stacking dried bones.

Those unfamiliar with what “a David Fincher film” means will no doubt see The Killer as a minor work or, at the very least, impenetrable. But Fincher takes what could be an impersonal story and turns it into the most self-reflective film in his career, and those who appreciate his particular auteuristic tendencies—from obsession to process, both on and offscreen—will savor the result. The director deftly walks a fine line, blending a procedural’s need for a strict methodology with the slight ironies and gradations of a layered character study. Somewhere amid the character’s cynicism and contradictions is an existential philosophy: “The only life path is the one behind you.” So even while following self-appointed rules, Fassbender’s character acknowledges that the whole universe is chaos. As much as he plans ahead, there’s no predicting what comes next, but it’s the only way he can make sense of everything. It’s a decidedly human perspective for someone who murders people for a living. But then, there’s often a profound, tender underbelly beneath the bitter surfaces of Fincher’s films.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review