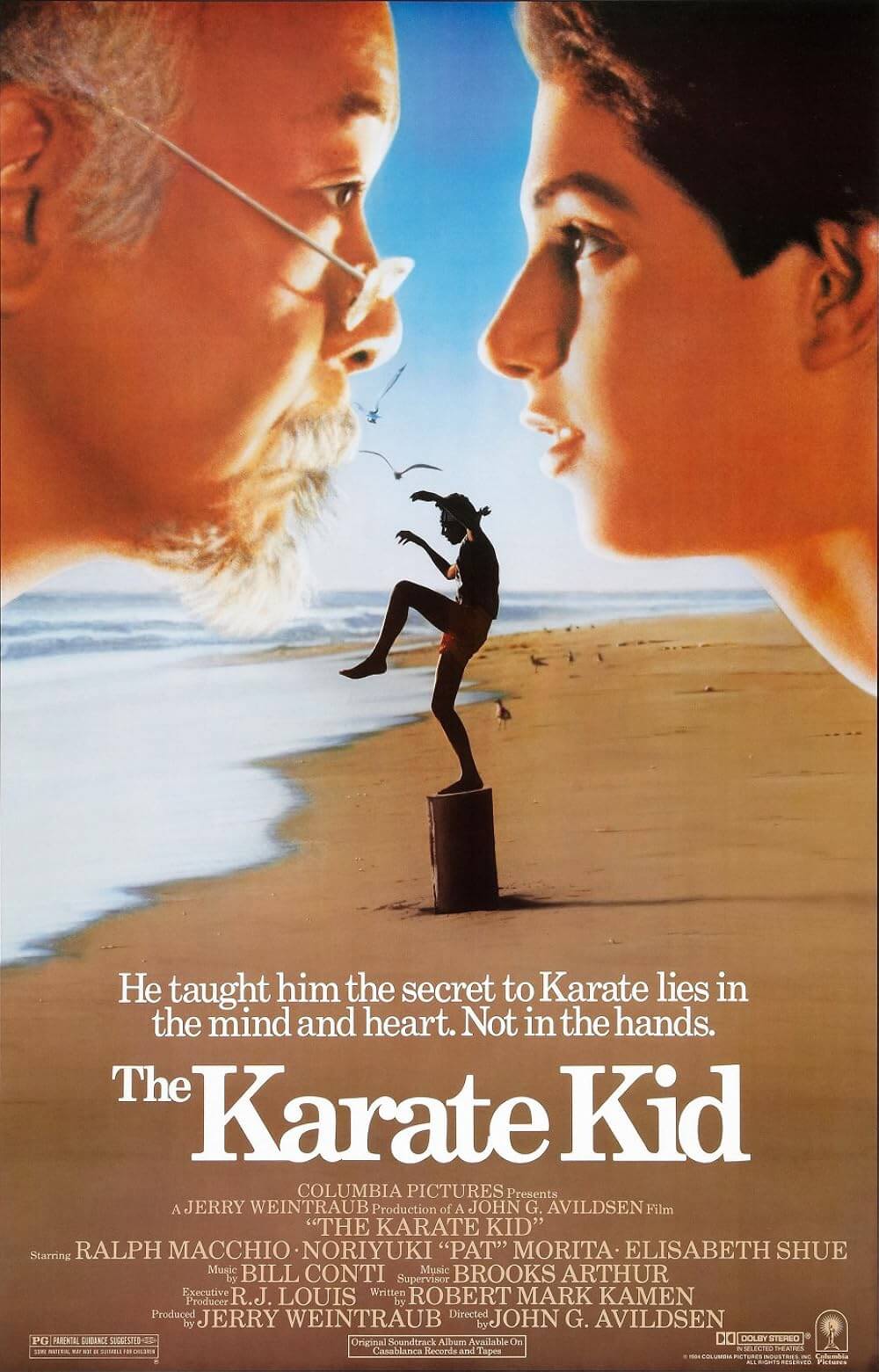

The Karate Kid

By Brian Eggert |

From the depths of the height of 1980s pop culture comes The Karate Kid, a motion picture that, despite being stamped by its decade of origin, still works on a basic dramatic level today. Saying nothing of the three sequels and modern remake that followed, the simplicity of Rocky director John Avildsen’s film comes from established formulas: the coming-of-age tale, the teenager overcoming adversity, and the Little Guy winning the Big Fight against all odds. Teeming with these clichés, the film surmounts any downfalls that might hinder it by also presenting admirable and tangible relationships at the core, and that’s what still works in viewings today.

Ralph Macchio plays wimpy pipsqueak Daniel LaRusso, who’s uprooted from his New Jersey home and relocated to Los Angeles thanks to a career change by his single mother (Randee Heller). He has trouble adjusting after he falls for the dreamiest girl in his class, Ali Mills (standard ‘80s heartthrob Elizabeth Shue). She’s the ex-girlfriend of the high school’s snobby bully, Johnny Lawrence (William Zabka), a black belt in the local karate dojo, Cobra Kai. Aryan by design, the elitist blond-haired, blue-eyed Johnny aggressively pursues Ali after the breakup and proceeds to batter the weakling Daniel for making eyes at his former girl. Here, all components of your standard melodrama fall into place, with the underdog new kid from the wrong side of town positioned against the elitist bully. He’s paired in an unlikely romance with the rich girl, and he’s forced to defend both his and her honor.

Befriending his apartment complex’s humble old maintenance man from Okinawa, Mr. Miyagi (Noriyuki “Pat” Morita), Daniel finds himself a valuable mentor. Together they groom bonsai trees and speak of Daniel’s YMCA experience with karate. One night, Daniel is rescued by Miyagi from a savage beating exacted by Johnny’s gang of hooligans. Miyagi turns out to be an unlikely karate master and resolves to teach Daniel; he even asks Johnny’s karate sensei, the dogmatic Vietnam Vet John Kreese (Martin Kove), to let the boys resolve their differences in an upcoming tournament. And opposed to a quick training montage and a swift resolution, the film swells and deepens in the training scenes, building upon the friendship between student and teacher. Daniel questions his lessons, why Miyagi has him doing manual labor—waxing cars, painting fences, sanding wooden floors—as opposed to teaching punches and kicks. And the reveal of Miyagi’s technique remains as fascinating as ever.

What works best in this film is not the glory of Daniel’s predictable victory at the final karate tournament. Actually, the fight scenes consume little screen time, as though the script knows that we know that Daniel will win no matter what—so why dwell on it? The fights are brief, over in an instant, and not even the karate match between Daniel and the Aryan spawn Johnny Lawrence is dragged out too long for dramatic effect. The audience is more concerned about Daniel gaining enough confidence to be with Ali, or Daniel honoring Miyagi with a fine performance in the tournament. These relationships are central to the story more than fighting. As Miyagi teaches, honor and balance in terms of the spirit and the body are superior concepts to merely destroying everything in one’s path with a karate chop. Such principles are what one takes away from a viewing of The Karate Kid today. The violent aspects of martial arts are almost completely forgotten next to these values, and so the film remains highly resonant on both emotional and moral planes.

What works best in this film is not the glory of Daniel’s predictable victory at the final karate tournament. Actually, the fight scenes consume little screen time, as though the script knows that we know that Daniel will win no matter what—so why dwell on it? The fights are brief, over in an instant, and not even the karate match between Daniel and the Aryan spawn Johnny Lawrence is dragged out too long for dramatic effect. The audience is more concerned about Daniel gaining enough confidence to be with Ali, or Daniel honoring Miyagi with a fine performance in the tournament. These relationships are central to the story more than fighting. As Miyagi teaches, honor and balance in terms of the spirit and the body are superior concepts to merely destroying everything in one’s path with a karate chop. Such principles are what one takes away from a viewing of The Karate Kid today. The violent aspects of martial arts are almost completely forgotten next to these values, and so the film remains highly resonant on both emotional and moral planes.

Of course, there’s no denying the cultural signifiers evident in the picture, which leave a “made in the 1980s” stamp all over the production. Just as Avildsen forever associated Rocky and its sequels with the inclusion of Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger” on the soundtrack, The Karate Kid seems irredeemably connected to the corny fighting ballad “You’re the Best” by rocker Joe Esposito. This song plays over the montage of karate matches in the tournament finale, echoing as the hundred-pound Daniel makes quick work of his opponents. That, along with the undeniable period hairdos and clothing, make the film more difficult to watch in a manner other than as a product of its time.

What’s even more distracting is the presentation of the villains, the karate students of Cobra Kai dojo, led by their Hitler, John Kreese, and his Goebbels, Johnny Lawrence. The film portrays Kreese as a senselessly violent man who believes in a “no mercy” brand of karate, which doesn’t seem like karate at all. Kreese’s minions, driven by his sense of irrational hatred for all things viewed as weak, haunt the temperate Daniel. Consider the Halloween scene where Cobra Kai’s SS troops all dress in skeleton costumes; it’s disturbing stuff. Like good little drones, they wittingly follow Kreese’s instruction to use illegal moves on Daniel during the tournament. They’re shown in such a sympathy-less light that, despite Daniel’s victory, we still hunger for Kreese to receive a harsh thrashing in retribution. Alas, that’s what sequels are for.

In terms of acting, Macchio’s vulnerability is impressive, and he does wonders with the role. But this is Morita’s film. It would be easy for screenwriter Robert Mark Kamen to limit Miyagi to your typical Yoda-type station, playing the other-worldly trainer who introduces his student to a new realm of thought. But thanks both to Morita’s Oscar-nominated performance and Kamen’s adept writing, the role proves to be so much more. Miyagi serves as both teacher and father figure to Daniel, but he’s also his own three-dimensional character. There’s an affecting scene where Daniel finds Miyagi drunk; the old man proceeds to confess the horrible tragedy of his past, the death of his wife and child. It’s an unbelievably sad moment that serves to humanize the character more than the audience expects. Morita, best known under the nickname “Pat” from his time on Happy Days, insisted upon the inclusion of his true name, Noriyuki, in the credits. Perhaps to seem less Americanized, given the nature of the role; perhaps because he wanted his true name to appear on this fine performance.

Opening in the summer of 1984, one of cinema’s most memorable periods where titles like Ghostbusters, Gremlins, and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom were released, The Karate Kid stands out as a film that embraces the clichés of its genre and does so with a surprising amount of class. Without relying too much on its own karate gimmick, it stands as an affecting drama about relationships. Morita and Macchio offer incredible performances in a film that started an increasingly worsening franchise, as the subsequent sequels tried and failed to achieve the same sense of emotional clarity as this first entry. And even though it contains a dated quality and the conflict has been grossly exaggerated by inhuman antagonists, on its own and separate from what came after it, The Karate Kid still works on a very basic level today.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review