The Jungle Book

By Brian Eggert |

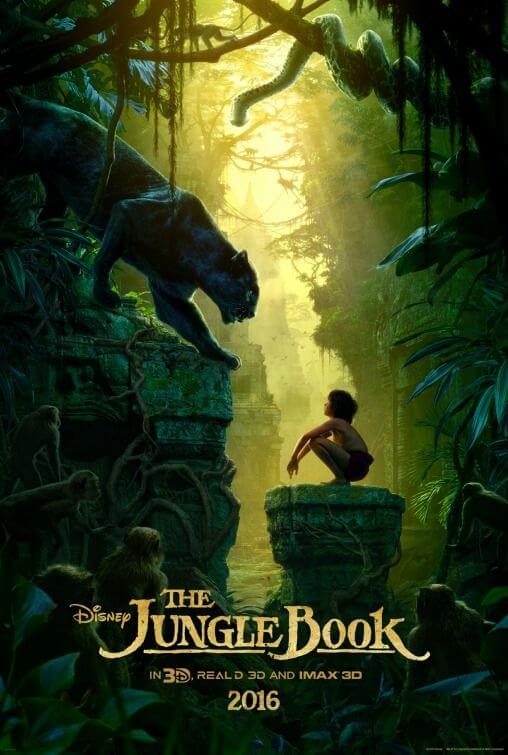

Less a take on Rudyard Kipling’s famous stories than a recycling of Walt Disney Productions’ 1967 adaptation, The Jungle Book follows Disney’s recent trend of creating live-action versions of their classic animated films. Although not revisionist like Maleficent (2014) but with more life than Cinderella (2015), director Jon Favreau’s peril-toned and wonderful looking film draws from the same sources as the 1967 version—namely, Kipling’s short story “Mowgli’s Brothers”, which appeared in his collection The Jungle Book (1894), as well as elements from The Second Jungle Book (1895). Shot entirely using blue screens and the occasional physical setpiece, Favreau constructs with a digital paintbrush to render his backgrounds and animals, delivering an impressive feast for the eyes. Although, remarkably, the production was all filmed in Los Angeles, it boasts incredible photo-real jungle visuals.

Ironically, the most unreal aspect of Favreau’s film is the unpolished acting by Neel Sethi, playing the young Mowgli. Regrettably, the wobbly child actor appears in almost every scene of the familiar story, which finds Mowgli raised by his adoptive wolf parents Raksha (Lupita Nyong’o) and Akela (Giancarlo Esposito), who do their best to bring up a human child as a wolf. Mowgli’s other invested guardian, the black panther Bagheera (Ben Kingsley), tries to prevent the boy from relying on his “tricks”, meaning the inherent human quality to make tools. But Mowgli’s presence in the jungle becomes a problem for the malevolent Bengal tiger Shere Khan (Idris Elba), who first sees Mowgli when the animals must make a “water truce” during a dry season (a very political moment not sourced from Kipling; instead, it feels more like Richard Adams’ Watership Down). Having been scarred from the “red flower” (fire) of humans, Shere Khan demands the boy be turned over, but Bagheera leads Mowgli into the jungle, where he’s to be delivered back to a Man Village.

This early section of Justin Marks’ screenplay comes and goes rather quickly, making way for its most inspired scenes, when Mowgli bonds with the informal stylings of bear-friend Baloo, voiced by Bill Murray (whose voicework fits this lazy animal much better than Garfield). If there’s one animal character in The Jungle Book who risks entering the Uncanny Valley of looking like his human counterpart, it’s Baloo. This point is debatable, however, since Murray’s familiar attitude seems to synchronize so well with his character—the audience might just be unconsciously projecting the actor’s face onto the bear. Along with Murray, other characters prove almost distractingly well cast, to the degree that the choices are so obvious, the viewer has difficulty not seeing the voice actor behind the animal character. Orangutan Gigantopithecus honcho King Louie, strangely informed by Colonel Kurtz and Vitto Corleone, comes off quite wacky-then-imposing courtesy of Christopher Walken. Most effective is Scarlett Johansson’s voicework on Kaa, the snake capable of hypnotizing Mowgli (although with a much different outcome than Johansson’s hypnotic efforts in Under the Skin). The late great Garry Shandling also lends his voice as Ikki, the edgy porcupine.

The casual, playful 1967 version of The Jungle Book was the last animated feature personally overseen by Walt Disney, and so it carries a certain bittersweet quality amid its usual early Disney magic. Favreau’s update ungainly nods back to the original by adopting two of the animated original’s memorable songs. Renewed versions of “The Bare Necessities” sung by Baloo and “I Wanna Be Like You” sung by King Louie (courtesy of Walken, a well-known song-and-dance man) feel like obligatory tissue connecting back to the original, whereas “Trust in Me,” performed by Kaa, curiously appears over the end credits. Other songs from the original are omitted completely, leaving us to presume Disney demanded Favreau acknowledge the original, no matter how inconsistent it left the overall film. Luckily, the impressive FX work allows the film to stand on its own after the tonally off-putting songs pass.

Perhaps it’s insulting to live-action features to call The Jungle Book a live-action production, since the majority of its shots have been painstakingly brought to life by CGI wizards and their impressive computers. The ratio of animation to reality outweighs even Avatar (2009), since there were far more humans onscreen in James Cameron’s film. In many ways, Favreau’s production has much more in common with something like Robert Zemeckis’ The Polar Express (2004), since the animated animals and jungle setting have all been artificially created and animated in such a way that they appear photo-real (at least, when their mouths aren’t moving). Even though it’s strange to watch incredibly realistic-looking animals speak like the cartoons in Disney’s original, the undeniable visual majesty of Favreau’s film overcomes any skepticism. And fortunately, the effect isn’t so off-putting as, say, the motion-capture work on Zemeckis’ other mo-cap features, Beowulf (2007) or A Christmas Carol (2009).

The end result of The Jungle Book requires a post-modern viewer to not get caught up in the details and periodic inconsistencies. Some may just sit back and enjoy the visual spectacle and pretty pictures onscreen, of which there are many, quite undeniably. And, of course, the sheer power of Kipling’s narrative cannot help but bond us to Mowgli’s journey. No matter how rough-around-the-edges Sethi’s acting may be, the animal characters are nothing short of believable. But other viewers may have trouble separating the CGI plane from the rare plane of reality on which Mowgli exists. Occasionally, Mowgli looks as though he’s standing on a studio lot in front of a screen. These rare moments clash with our suspension of disbelief. Younger viewers and audiences oblivious to this separation of the real and animated will savor The Jungle Book as a new classic, while the rest of us anticipate the next Disney live-action update with measured optimism.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review