The Island of Dr. Moreau

By Brian Eggert |

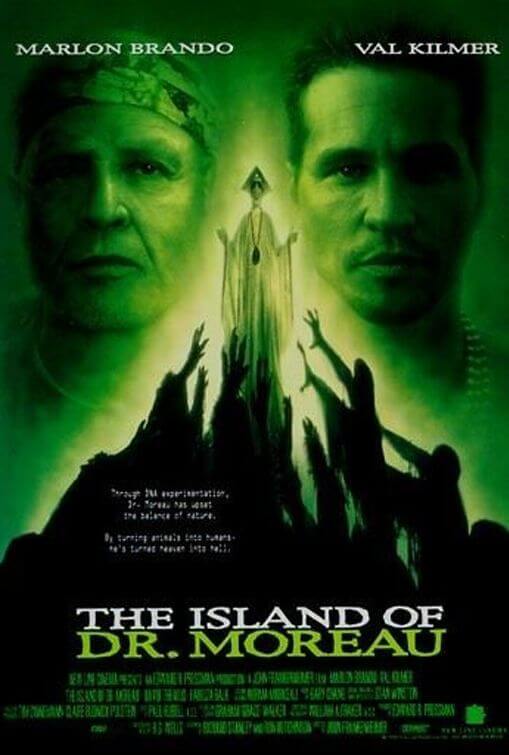

Before John Frankenheimer adapted it in 1996, two versions of H.G. Wells’ novel The Island of Doctor Moreau—the story of a mad scientist who runs a colony where he performs human-animal vivisections like a zoological Nazi doctor—were produced in Hollywood. Paramount Pictures released the first version in 1932 called Island of Lost Souls, a wonderfully unsettling and scary picture starring Charles Laughton as the resident doctor and Bela Lugosi as the Sayer of the Law among Moreau’s Beast Folk. Next, Burt Lancaster played Moreau in 1977’s The Island of Dr. Moreau for American International Pictures, the second take, which also starred Michael York as the lifeboat survivor who ends up on Moreau’s island, only to discover Moreau’s nightmarish experiments firsthand. Frankenheimer’s version is strange and widely regarded as a disaster, but it doesn’t set out to be a horror film as its predecessors resolved to be, which makes it unique. Regardless, it’s also one of the most despised pictures in Frankenheimer’s career. Perhaps rightfully so, as it embraces man-in-animal-suit chaos over the commentaries in the book about the dangers of exploratory science and savagery of the human race. In the years since its release, the film’s sour reputation has carried on strong and not improved with time.

Intended to coincide with the centennial of Wells’ book, Frankenheimer’s troubled production finally hit screens in August of 1996 to a whirlwind of critical bashing and audience indifference. But The Island of Dr. Moreau was originally conceived as a passion project by Hardware (1988) director Richard Stanley, which New Line Cinema agreed to finance after Stanley secured Marlon Brando to play Moreau and Val Kilmer as the protagonist, the shipwrecked Edward Douglas. However, unthinkable disasters and personal acts of sabotage amid the cast and crew led the production into a downward spiral from which it barely recovered. Some might argue that it never recovered. And they would be right. In an article in a May 1996 issue of Entertainment Weekly called “Psycho Kilmer”, published just three months before the film’s release, Rebecca Ascher-Walsh detailed Val Kilmer’s suspected breakdown and how he, almost single-handedly, caused the film’s notorious on-set troubles.

Just prior to filming with Stanley behind the camera, Kilmer received a notice of divorce from his then-wife, actress Joanne Whalley. With several hits to his name—including The Doors (1991), Tombstone (1993), and Batman Forever (1995)—and multi-million dollar paychecks abound, Kilmer had begun to act out in erratic, even violent ways. His first bizarre act was to ask Stanley to reduce his role by forty percent; this has often been attributed to his divorce. Knowing New Line wanted Kilmer as a box-office draw, Stanley resolved to recast Douglas with TV’s Northern Exposure star Rob Morrow and place Kilmer in the role of Montgomery, Moreau’s animal wrangler and right-hand man. As filming began in Queensland, Australia, tensions were already high on set due to the last-minute recasting. Worse, Brando’s anxieties over his daughter Cheyenne’s recent suicide in April of 1995 and the French government’s underwater atomic test near his atoll (Brando, like Moreau, owned his own island) left him distracted; the actor refused to rehearse and instead was fed his lines from a small radio receiver in his ear. After just three days, Stanley’s inability to control his set or demanding actors led to New Line’s decision to replace Stanley with John Frankenheimer.

A veteran of both TV and film, Frankenheimer’s career blossomed in the Sixties with radical pictures like The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and box-office hits such as The Train (1965) and Grand Prix (1967). Since then, his career had petered out, and he’d become a director-for-hire on countless duds, although his string of Emmy-winning made-for-HBO movies in the 1990s had brought him back into the limelight. With his arrival on the set of The Island of Dr. Moreau, Frankenheimer demanded production shut down for more than a week while the screenplay by Stanley was rewritten by his own collaborator, Ron Hutchinson. The new director’s approach would be far less horrific than Stanley had planned and more like Apocalypse Now, complete with a psychologically shattered Brando character having gone mad with godlike power in the wilderness. Given the production troubles, Marrow departed, and the role of Douglas was filled by David Thewlis, the little-known indie actor from Louis Malle’s Damage (1992) and Mike Leigh’s Naked (1993).

A veteran of both TV and film, Frankenheimer’s career blossomed in the Sixties with radical pictures like The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and box-office hits such as The Train (1965) and Grand Prix (1967). Since then, his career had petered out, and he’d become a director-for-hire on countless duds, although his string of Emmy-winning made-for-HBO movies in the 1990s had brought him back into the limelight. With his arrival on the set of The Island of Dr. Moreau, Frankenheimer demanded production shut down for more than a week while the screenplay by Stanley was rewritten by his own collaborator, Ron Hutchinson. The new director’s approach would be far less horrific than Stanley had planned and more like Apocalypse Now, complete with a psychologically shattered Brando character having gone mad with godlike power in the wilderness. Given the production troubles, Marrow departed, and the role of Douglas was filled by David Thewlis, the little-known indie actor from Louis Malle’s Damage (1992) and Mike Leigh’s Naked (1993).

As production resumed, Frankenheimer clashed with Kilmer’s oddball behavior, including one instance where Kilmer taunted and burned a cameraman while lighting a cigarette. Another threat of blaze presented itself when the fired Richard Stanley remarked to production designer Graham Walker (Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome) how he planned to return to the set and burn it down. Stanley supposedly remained hidden on-set to watch Frankenheimer’s progress, all the while disguised as one of Moreau’s Beast Folk. When he revealed himself at the wrap party paid for by Brando, Kilmer apologized to Stanley for his behavior. Still, relations between Frankenheimer and Kilmer never improved. Of Kilmer, Frankenheimer quipped, “Will Rogers never met Val Kilmer”—referring to Rogers’ famous line “I never met a man I didn’t like.” Throughout Hollywood, Kilmer’s reputation had been forever soured. Brando famously told him, “Your problem is, you confuse your talent with the size of your paycheck.” No longer would Kilmer be a bankable star; over the next decade or more, he would gradually decline from million-dollar paydays to a heavy presence in the direct-to-video market.

Critics could not set aside set reports of the behind-the-scenes squabbling; not that such reports were needed to make The Island of Dr. Moreau an easy target upon its release. How could critics resist, after months of reading horror stories from the set, along with several last-minute casting and directorial choices by New Line? Few films have had a harder time getting to the screen than The Island of Dr. Moreau, only then to be lambasted and all but forgotten in subsequent years. The reviews were not kind: Variety critic Todd McCarthy called the film an “embarrassment for all concerned.” Over at the San Francisco Chronicle, critic Peter Stack called it “a maddening mess of empty gestures,” and went on to remark, simply, “It doesn’t quite compute.” At the box office, the film performed moderately well for the studio, but its legacy was shaped by its poor reception and later nominations for six well-earned Razzie Awards.

Granted, it’s not all bad. What sets the 1996 version apart from its predecessors is the depiction of Moreau himself, who in past productions and even the book was portrayed as an evil, irredeemable, maddened scientist and all that such a label entails within the genre. By contrast, Marlon Brando depicts Moreau as an almost gentle sort, a fatherly geneticist who creates his “children” not through gory vivisections, but relatively painless genetic splicing. For all the monstrous results and failed abominations floating in canisters in the laboratory “House of Pain,” Brando’s Moreau offers his children understanding and the possibility of more than a freakish existence. As their master, he teaches them to read and attempts to “cultivate” them with the law and an aversion to killing. He sees a blending of human and animal DNA as a higher form of existence. Of course, Moreau and his assistant Montgomery have been isolated from civilization for far too long, which comes out in their behavior—often cited among the film’s more inexplicable qualities.

Somewhere in the Java Sea, U.N. negotiator Edward Douglas floats in a raft after a plane crash. After watching his fellow survivors kill each other (an act of heavy-handed foreshadowing), he’s rescued by a passing ship and invited to radio for help on a nearby island along with Montgomery. He quickly discovers that Moreau, who’s long since vanished from the scientific community, has continued his obsession with animal research in seclusion. What he finds is Moreau and Montgomery serving as autocrats over a society of human-animal hybrids, the creatures controlled both by drugs and by implants that deliver an electrical shock when activated by “The Father”. When a creature called Hyena-Swine (Daniel Ringley) realizes this, he removes the implant and shows the others how to do the same. He then leads a revolt, and a massacre ensues in which Moreau and Montgomery meet their demise, while Douglas barely survives. Having witnessed Moreau’s abominations kill their master and resign their revolution after Hyena-Swine takes his own life in enraged shame, Douglas escapes the island and, in a bout of the film’s intermittent narration, remarks that human behavior is no better than Moreau’s creations.

Of Brando, Roger Ebert called The Island of Dr. Moreau “perhaps his worst film” and cited his considerable weight in the picture as distracting for an actor who had once played a toned biker gang leader in The Wild One (1953). When Brando first appears onscreen, his girth is indeed shocking, but then so was his husky appearance when Apocalypse Now debuted in 1979 (and by comparison, Brando’s Col. Kurtz is trim next to his Dr. Moreau). Almost a parody of his own Col. Kurtz, Brando’s Moreau speaks with a tangential absent-mindedness that defined his persona in the decades surrounding the picture, drifting from one subject to the next with equal parts genius and lunacy, but mostly just forced, intentional weirdness. Accompanied by his coddled, dwarfish double Majai (the two-foot-four-inch tall Nelson de la Rosa), he appears in a kind of linen gown, his face painted white to protect his delicate skin; atop his head, he wears a hat constructed out of an ice bucket, and he frequently complains about the tropical heat. Moreau’s behavior is not so completely that of a prototypical movie mad scientist, but rather that of an incredible eccentric who’s been left to his own whims for far too long. He’s not an outright monster or madman; nevertheless, he has long since lost himself in his pursuit of using science to improve the human race.

Frankenheimer must have realized Brando’s performance was, in its way, going to be iconic. Among the film’s most bizarre, hilarious moments is when a drugged Montgomery impersonates his employer; Kilmer, decked out in a Moreau costume, delivers a spot-on Brando as his character distributes psychedelics to the Beast Folk for an ensuing orgy. As for Montgomery’s own eccentricities, Kilmer leaves a pointless mystery to this ill-defined character, incorporating questionable and curious details into his appearance and behavior. As Montgomery is an avid drug user, the audience can only assume the blue band around Kilmer’s elbow is meant to hide track scars, but who can say? Throughout the picture, Frankenheimer allows and includes such details to create a prevailing sense that there’s something very wrong with this island, but these are superficial details and nothing more. Fortunately, his film doesn’t degrade into pure horror, but it gradually resembles the long journey taken by Martin Sheen’s Willard in Apocalypse Now—wherein our protagonist ventures into a tribal, chaotic, and in time violent “heart of darkness” led by a man who has lost any semblance of his former brilliant self.

Frankenheimer must have realized Brando’s performance was, in its way, going to be iconic. Among the film’s most bizarre, hilarious moments is when a drugged Montgomery impersonates his employer; Kilmer, decked out in a Moreau costume, delivers a spot-on Brando as his character distributes psychedelics to the Beast Folk for an ensuing orgy. As for Montgomery’s own eccentricities, Kilmer leaves a pointless mystery to this ill-defined character, incorporating questionable and curious details into his appearance and behavior. As Montgomery is an avid drug user, the audience can only assume the blue band around Kilmer’s elbow is meant to hide track scars, but who can say? Throughout the picture, Frankenheimer allows and includes such details to create a prevailing sense that there’s something very wrong with this island, but these are superficial details and nothing more. Fortunately, his film doesn’t degrade into pure horror, but it gradually resembles the long journey taken by Martin Sheen’s Willard in Apocalypse Now—wherein our protagonist ventures into a tribal, chaotic, and in time violent “heart of darkness” led by a man who has lost any semblance of his former brilliant self.

For much of the film, when Brando is present, the material proves mildly entertaining. Except, he’s onscreen for only a short period before Moreau dies, and then the whole third act plays out like a choppily assembled mess of the Beast Folk rebellion, with the creatures shooting machine guns and shouting “fetch” at one another. Somewhere underneath it all is a message about humans behaving like animals, but who could ever find it under all the mindless killing and Montgomery’s eventual downswing into a drug-induced mania? Today, Stan Winston’s Beast Folk creature makeup and, overall, the film’s laughable CGI lend a campy quality to the production. The Island of Dr. Moreau remains a curiosity in Frankenheimer’s career and is distinct for its unique approach to the otherwise heavily mined material. Most involved all but disowned the picture after its release (Thewlis refused to attend the premiere), and who can blame them? It’s a grotesque, frenzied, sci-fi-infused take on Apocalypse Now, and it’s a decided low point for the often exceptional Frankenheimer. Sometimes the stigma perpetuated by a film’s very public behind-the-scenes difficulties is unfounded, but this is not one of those cases. Upon revisitation of the film, not even the most devoted Frankenheimer enthusiast will find a coherent outcome, no matter how layered it may be with admirable degrees of pure oddity and (arguably intentional) hokum.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review