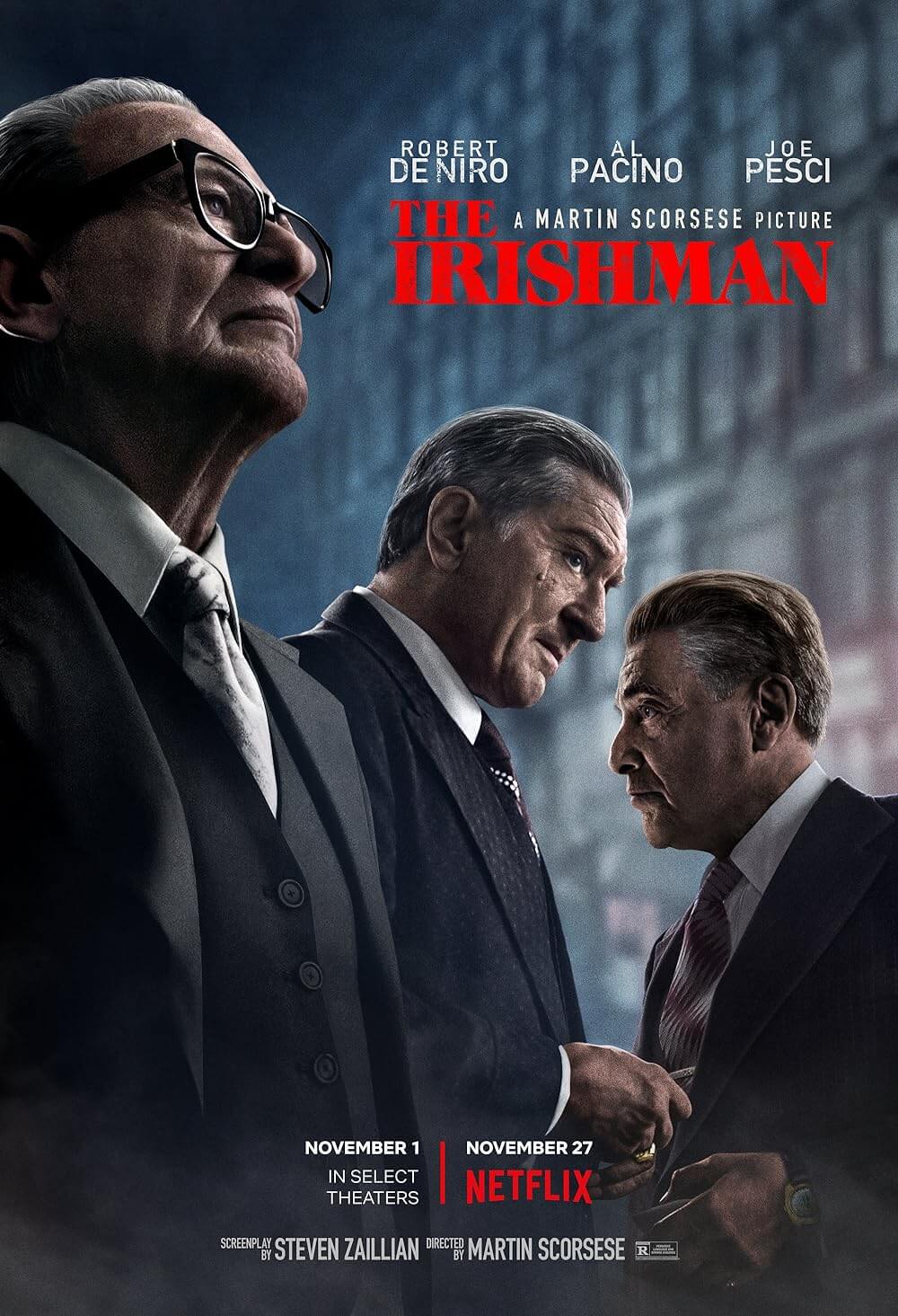

The Irishman

By Brian Eggert |

Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman is a reunion, marking the director’s return to the gangster genre with the actors who starred in his most famous films. The film rejoins its director with his once-perennial leading man Robert De Niro, along with Joe Pesci, Harvey Keitel, and others, after more than two decades. The screenplay, written by Steven Zaillian, was adapted from Charles Brandt’s 2004 book, I Heard You Paint Houses, whose title refers to a mob code for hitmen who paint the walls with blood. To whatever degree the material brings to mind Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995), Scorsese and Zaillian have turned this non-fiction account into something else entirely. The story follows mob enforcer Frank Sheeran, who claimed to have killed Jimmy Hoffa, into a sprawling yet improbable film that weaves history and cold-blooded killers with a lingering sense of self-reflection. Netflix paid an incredible $150 million to complete The Irishman, the cost owing to the special FX that make its cast of veteran actors appear younger, even though such budgetary highs are usually reserved for Hollywood franchises—not for a three-and-a-half-hour film whose somber tone and effusive drama stray far from the mainstream path. Composed in a steady, immersive rhythm and marked by belated contemplation from its passive protagonist, the textured film is a massive achievement and monument to figures, both onscreen and off, reflecting on life from their twilight years.

Zaillian’s screenplay arranges The Irishman’s story within two framing devices. It opens with a leisurely stroll through a retirement home, a continuous take to echo the Steadicam shot through the Copacabana in Goodfellas. It sees elderlies in wheelchairs, having their monthly visits with their offspring; it passes by nurses and holy men tending to the residents; and after passing through a long corridor and settling in a commons area, it finds the octogenarian Frank Sheeran (De Niro) sitting alone. He looks like any number of withered older men in that place, except for a large gold ring on his left hand, and cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto subtly drops the frame to notice it. All at once, Frank plunges into a story, dropping names and places of which his audience is not yet familiar. He takes us back to 1975, when Frank, an enforcer of Irish decent, and Russell Bufalino (Pesci), a powerful Italian mobster, drive their wives from their home base in Philadelphia to a wedding in Detroit—the road trip that will eventually lead to Frank killing his friend, Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino). But on one of their regular cigarette breaks, necessary because Russell does not allow smoking in his car, Frank notices the gas station where he and Russell met by chance twenty-five years earlier. The film then takes us back to 1950, and from there, the story unfolds in chronological order, returning to the road trip or Frank as an old man in the nursing home in a novelistic shape.

Within the first few moments, as this structure solidifies, Scorsese establishes themes of time and memory, the expanse and connections between youth and old age that congregate in Frank’s aging mind. The 77-year-old director seems to dwell on these themes just as his central character does, informing his cast, the subject matter, and the digital technology used to bring the story to life. After nine features together, Scorsese and De Niro remain among the finest director-actor pairings in film history, but since they worked together last in Casino, De Niro’s work has taken a steady decline (apart from his work with David O. Russell). One of The Irishman’s many treasures is reminding viewers what a superb actor De Niro can still be when tested. Along with frequent collaborators De Niro and Pesci, the director casts Keitel and Pacino, two actors long associated with the gritty crime cinema of yesteryear, though The Irishman, amazingly, marks Pacino’s first time working with Scorsese. The actors’ ages range from 75 to 80, though “de-aging” technology returns them to their former glory, or at least some semblance of it. De Niro looks younger in the flashbacks to 1950, though he resembles a blushed picture postcard of the era. Far from his once slender frame in Taxi Driver (1976), De Niro has the bulk, movements, and broader nose of a much older man, even if his character is meant to look 30. It’s an initially distracting technique that becomes easier to ignore as the film goes on. But his appearance is also fitting, as though Frank’s memory of his past and his present reality have converged in the mind of the narrator.

Within the first few moments, as this structure solidifies, Scorsese establishes themes of time and memory, the expanse and connections between youth and old age that congregate in Frank’s aging mind. The 77-year-old director seems to dwell on these themes just as his central character does, informing his cast, the subject matter, and the digital technology used to bring the story to life. After nine features together, Scorsese and De Niro remain among the finest director-actor pairings in film history, but since they worked together last in Casino, De Niro’s work has taken a steady decline (apart from his work with David O. Russell). One of The Irishman’s many treasures is reminding viewers what a superb actor De Niro can still be when tested. Along with frequent collaborators De Niro and Pesci, the director casts Keitel and Pacino, two actors long associated with the gritty crime cinema of yesteryear, though The Irishman, amazingly, marks Pacino’s first time working with Scorsese. The actors’ ages range from 75 to 80, though “de-aging” technology returns them to their former glory, or at least some semblance of it. De Niro looks younger in the flashbacks to 1950, though he resembles a blushed picture postcard of the era. Far from his once slender frame in Taxi Driver (1976), De Niro has the bulk, movements, and broader nose of a much older man, even if his character is meant to look 30. It’s an initially distracting technique that becomes easier to ignore as the film goes on. But his appearance is also fitting, as though Frank’s memory of his past and his present reality have converged in the mind of the narrator.

In another way, Scorsese looks back at a career sprinkled with gangster films and stories about the Italian mob. Goodfellas and Casino took a harsh, critical look at the world of organized crime and forever associated the director with the genre, while Mean Streets (1973) and Raging Bull (1980) existed on the periphery of those worlds. His lively and formally daring films from the first half of his career have blustering, youthful energy that crackles with bravado and showy technique, along with wall-to-wall rock music on the soundtrack. Where the Rolling Stones’ “Gimmie Shelter” was once Scorsese’s musical calling card, The Irishman finds him in an altogether different mode more suited to the film’s contemplative state. Rather than songs that strut and roar onto the screen, his latest uses the circuitous “shoo doop shooby doo” from The Five Satins’ “In the Still of the Night” and Robbie Robertson’s harmonica-inflected score that sounds like Once Upon a Time in Pennsylvania—music that signals a steady winding and consideration of the past. Given Scorsese’s use of these actors in the crime genre that defined each of their careers, it might seem as though The Irishman has rooted itself in nostalgia for their earlier work, offering one last lap around a familiar track. And while nostalgia does have a role to play, the film’s self-reflection and examination of the past leads to something far more profound than a reunion tour.

If The Irishman could be reduced to a single narrative conceit, it would be to shed light on the fate of Jimmy Hoffa, the Teamsters Union leader whose disappearance in 1975 has led to several theories about his death. Was he buried under Giants Stadium? Was he killed by mafia hitman Richard Kuklinski? The mystery remains to this day, though experts and authorities almost unanimously believe some faction of organized crime silenced him. Around that time, Hoffa tested his former mob associates with petty interpersonal feuds, especially with Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano (played by Stephen Graham), while his public critiques of the mob and efforts to retake the Teamsters endangered their financial interests. In the film, Pacino plays Hoffa in a loudmouth, unhinged caricature whose populist speechifying rallies the average working man. Driven by a stubborn refusal to control himself or cease his maneuvers to restore “his” union—though it was run by another man, Frank Fitzsimmons, after Hoffa was sent to prison for jury tampering in 1971—Hoffa eventually finds himself shot by Frank Sheeran, his friend and fellow union compatriot. But Sheeran was just one of several suspects in Hoffa’s death, and many writers have since refuted these claims since the publication of Brandt’s book.

Nevertheless, The Irishman unfurls its historical canvas to reveal Frank at the center, like Forrest Gump, with a small role in landmark moments of American history, from the Bay of Pigs to the Kennedy assassination. After serving in World War II under General Patton, where he carried out cold executions of German prisoners as a matter of following orders, Frank returns home to a job as a lowly truck driver, transporting cuts of meat from a warehouse to various restaurants around Philadelphia. He’s married with children, and after the birth of his latest child, he needs more money, so he starts taking odd jobs from local gangsters, Felix “Skinny Razor” DiTullio (Bobby Cannavale) and made man Angelo Bruno (Keitel). His effectiveness and honesty earn him the trust of the Philadelphia mob, the high-powered Russell above all. He plugs along, doubling as a union official and mob functionary under the wing of his Cosa Nostra mentor. But it’s evident that he’s an efficient working stiff, regardless of whether he’s driving a truck or delivering a few matter-of-fact bullets into the head of a mob target. Soon enough, he’s assigned to protect Hoffa, whose dealings with the mob allow them to build lucrative casino hotels. Frank is never the smartest guy in the room, but he’s a reliable hunk of middle management, capable of getting the job done, and done well. He takes orders, stutters when he’s confronted by his betters, and seems to have no moral compass that limits what actions he’ll take in service of his duties.

Nevertheless, The Irishman unfurls its historical canvas to reveal Frank at the center, like Forrest Gump, with a small role in landmark moments of American history, from the Bay of Pigs to the Kennedy assassination. After serving in World War II under General Patton, where he carried out cold executions of German prisoners as a matter of following orders, Frank returns home to a job as a lowly truck driver, transporting cuts of meat from a warehouse to various restaurants around Philadelphia. He’s married with children, and after the birth of his latest child, he needs more money, so he starts taking odd jobs from local gangsters, Felix “Skinny Razor” DiTullio (Bobby Cannavale) and made man Angelo Bruno (Keitel). His effectiveness and honesty earn him the trust of the Philadelphia mob, the high-powered Russell above all. He plugs along, doubling as a union official and mob functionary under the wing of his Cosa Nostra mentor. But it’s evident that he’s an efficient working stiff, regardless of whether he’s driving a truck or delivering a few matter-of-fact bullets into the head of a mob target. Soon enough, he’s assigned to protect Hoffa, whose dealings with the mob allow them to build lucrative casino hotels. Frank is never the smartest guy in the room, but he’s a reliable hunk of middle management, capable of getting the job done, and done well. He takes orders, stutters when he’s confronted by his betters, and seems to have no moral compass that limits what actions he’ll take in service of his duties.

Frank takes a passive role in his relationships with Russell and Hoffa. With Russell, who calls him “kid,” Frank is a child in a father-son pairing. Russell and his wife cannot have children of their own, so he all but adopts Frank, protecting him and, at long last, welcoming the Irish outsider into the Italian family with the rare gift of a ring. The two share genuinely affecting scenes together in their road trip before Hoffa’s death, and the unspoken intimacy between them is never more palpable than in a scene over cereal in a Howard Johnson’s motor lodge. Meanwhile, Frank’s rapport with Hoffa is a marriage. As Hoffa’s bodyguard and confidant, Frank stays with him in hotels; they sleep next to each other in twin beds, like a couple in a classic Hollywood movie, talking to each other in their pajamas. But Frank’s allegiance to Russell supersedes his friendship with Hoffa, and he serves as a go-between when the tension between them heats up, like a child asked to pass messages between divorced parents. His subservient roles with Russell and Hoffa are, surprisingly, not counteracted by scenes of Frank at home as the paterfamilias—those scenes do not exist in The Irishman. Scorsese barely acknowledges the relationships between Frank and his wives, and the transition between his first wife and his second is handled between cuts, as it seems to have no significant consequence on Frank’s life.

If the emotional core of The Irishman resides in Frank’s male relationships, its height comes as Frank is tasked with killing his friend. The mob has grown tired of Hoffa’s dogged attempt to reacquire power over the Teamsters, and they ask Frank to appeal to his friend. He pleads with hints of desperation (“I’m trying to help you”) because he knows what comes next, but Hoffa refuses to listen to reason through several, cringe-worthy confrontations that recall the fate of Morrie Kessler from Goodfellas—the loudmouth who didn’t know when to quit. In the long sequence leading to Hoffa’s death, Scorsese relishes minor details in a car ride, including a quirky conversion about fish with Hoffa’s foster son, Chuckie O’Brien (Jesse Plemons). The director avoids dwelling on violence as he has done in the past, preferring to immerse the viewer in the tense moments of build-up. In a sequence where Frank plans a hit of Joseph “Crazy Joe” Gallo (Sebastian Maniscalco), his narration about how to choose a gun and how to approach the location sounds like a blue-collar worker reasoning out a menial task. Much earlier, Scorsese plunges his camera into a bouquet of flowers rather than show a scene of violence. To be sure, the director has other things on his mind here, demonstrating a far more mature, thoughtful work.

With The Irishman’s violence subdued and its central character passive, the film’s conscience emerges as Frank’s daughter, Peggy, a near-voiceless character whose arresting glances haunt the film. As a child, played by Lucy Gallina, Peggy looks deep into the souls of Frank and Russell, at once frightened and condemning of their suspected criminal behavior (she first witnesses her father’s capacity for violence when he beats a grocer in front of her). She silently avoids Russell, sensing he has dark secrets, whereas the more genial Hoffa has delighted her with his penchant for ice cream sundaes and open-hearted warmth. Later, when Anna Paquin plays Peggy as an adult, her looks of suspicion become certainty when Hoffa goes missing, yet her father still hasn’t called Jo Hoffa (Welker White) days after the disappearance. Her line, “Why haven’t you called?” is a punishing accusation, followed by an aching scene in which Frank must call Jo and feign optimism that her husband will turn up, even though he knows she’s a widow because of him. Peggy remains the only character who processes the moral consequences of the violence and criminality throughout the film, which is carried out by men who lead unexamined lives. The moment late in the film when she walks away from her father, who is now elderly and barely able to walk, represents the final judgment.

With The Irishman’s violence subdued and its central character passive, the film’s conscience emerges as Frank’s daughter, Peggy, a near-voiceless character whose arresting glances haunt the film. As a child, played by Lucy Gallina, Peggy looks deep into the souls of Frank and Russell, at once frightened and condemning of their suspected criminal behavior (she first witnesses her father’s capacity for violence when he beats a grocer in front of her). She silently avoids Russell, sensing he has dark secrets, whereas the more genial Hoffa has delighted her with his penchant for ice cream sundaes and open-hearted warmth. Later, when Anna Paquin plays Peggy as an adult, her looks of suspicion become certainty when Hoffa goes missing, yet her father still hasn’t called Jo Hoffa (Welker White) days after the disappearance. Her line, “Why haven’t you called?” is a punishing accusation, followed by an aching scene in which Frank must call Jo and feign optimism that her husband will turn up, even though he knows she’s a widow because of him. Peggy remains the only character who processes the moral consequences of the violence and criminality throughout the film, which is carried out by men who lead unexamined lives. The moment late in the film when she walks away from her father, who is now elderly and barely able to walk, represents the final judgment.

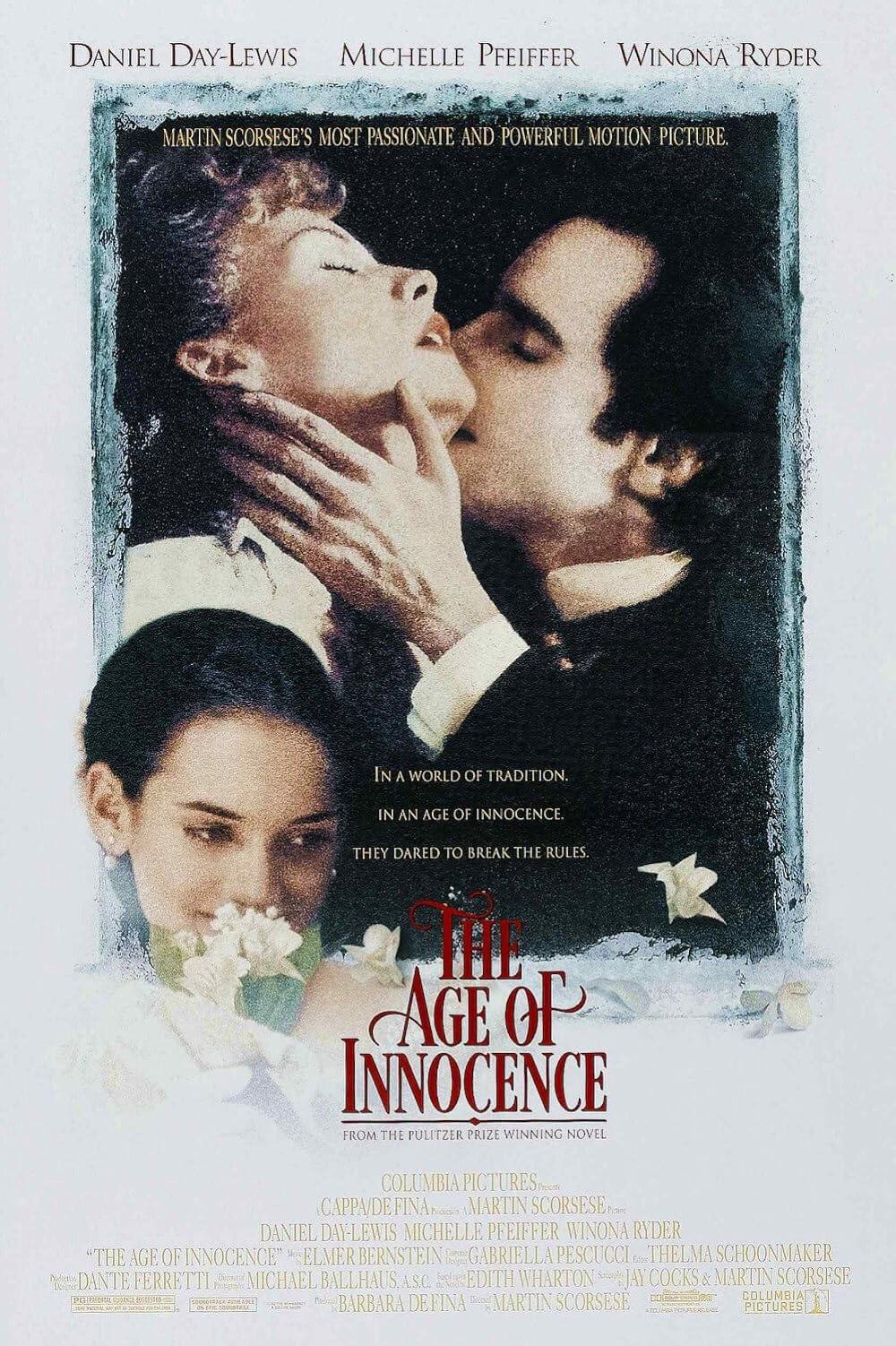

From a certain perspective, Frank could be considered a remorseless psychopath who only begins to feel some measure of regret in his aged years, when he’s the last man standing after most of the top figures in the mob either died of old age or were cleared out by violence. A recurring freeze-frame motif uses titles like an onscreen grave marker to announce how most of the gangsters introduced in the story meet a bloody end off-screen. Combined with the framing devices, which return us to Frank in the nursing home periodically, these death titles remind us that Frank, a mere foot soldier, outlives them all. In the final nursing home scenes, a priest asks Frank, “You don’t feel anything at all?” about the harm he’s caused. Frank must admit that, even in his solitude, he has no regrets. Except, he’s left with a nagging impulse to pray. Though The Irishman may earn comparisons to the director’s gangster films given its setting, it bears a greater similarity to The Age of Innocence, Scorsese’s 1992 masterpiece in which Daniel Day-Lewis’ Newland Archer is repressed by the strict rules of New York’s high society, forced to live an unfulfilled life of quiet acceptance. Likewise, Frank has served his employers with unquestioned devotion for more than half a century. His various resignments—“Whatever happens, happens” or “What am I gonna do?”—reveal a passive existence. And though it allowed him to support his family and some personal renown, what has it gotten him? Both Frank and Newland Archer live to an old age, only to look back at their lives of toeing the line and feel the smallest inkling of lament. Their lives are achingly tragic.

Unlike anything Scorsese has made, The Irishman bears an indefinable quality that goes with some of his outlier films, such as Kundun (1997) or Silence (2017). It’s a deceptive, carefully calibrated film, the likes of which rarely ever get made—in fact, with its huge price tag and confessional framework that settles into ambiguity, it’s safe to say that few films like this exist. The best comparison one could make to The Irishman is David Lean’s similarly epic-sized Lawrence of Arabia (1962), a biography that examines its subject for four hours before conceding to its unknowability. Even so, the cast and subject matter create the illusion that this will be another Scorsese gangster picture, but The Irishman is far more delicate than his earlier offerings. At the same time, so many strange details require acclimation: the youthifying CGI, the pensive tone, and the luxuriant runtime. Above all, the elusiveness of the narrative, along with the uncertainty of how we should feel about Frank, plants a seed in the viewer for further meditation. So much of this film is left unsaid, lost to history and memory, though it feels wholly complete. Still, one of Frank’s last lines (“What kind of man makes a phone call like that?”) declares a lifetime of unexpressed remorse that builds upon the viewer’s empathy and, since it does not occur until the last minutes of the film, enriches another viewing.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review