The Invisible Man

By Brian Eggert |

The mad scientist in Universal’s latest iteration of H.G. Wells’ novel, The Invisible Man, is called an expert in “optics,” a loaded term in the context of writer-director Leigh Whannell’s thrilling new film. Deconstructing the original scenario, first adapted in 1933 by filmmaker James Whale into the classic monster movie starring Claude Rains, Whannell introduces a villain who not only controls light to render himself transparent, but he manipulates and exploits the perception of those who witness his actions. For much of the film, Adrian Griffin, the titular antagonist, remains unseen, while the story’s focus is centered on his wife, Cecilia, played in an anchoring performance by Elisabeth Moss. By adopting her perspective, Whannell takes his version of The Invisible Man into a political space, delivering a slick parable for the #MeToo movement and the slogan “believe women” in our culture. It’s a film that acknowledges the biases against women who make accusations of abuse, harassment, or rape and find themselves disbelieved or challenged. Fortunately, the film never resorts to soapboxing these themes, even as they reside on the surface of the plot. Instead, Whannell delivers an often-terrifying experience that just happens to be achingly germane.

The Invisible Man is the latest attempt by Universal to reboot its classic monster characters, the intellectual properties that gave the studio legs back in the 1930s and 1940s. The Invisible Man belongs on a list including Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, the Mummy, the Wolf Man, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon—iconic characters and brands that over the last century have appeared in various remakes that tend to pale in comparison to their originals. Universal’s most recent attempt to apply the MCU’s treatment with the “Dark Universe” proved dead on arrival after 2017’s actionized The Mummy, a project with a budget of more than $150 million. The studio scrapped its plans for that extended universe, and with them, their development of a Johnny Depp-starring version of The Invisible Man. Universal then announced a new approach: they would once again rethink their franchises, not as uber-expensive blockbusters but as smaller-scale projects by filmmakers with a vision. Driven by Jason Blum’s production company Blumhouse, the project fell on Whannell, who has proved his acuity for modern horror as the screenwriter of Saw (2004) and Insidious (2010).

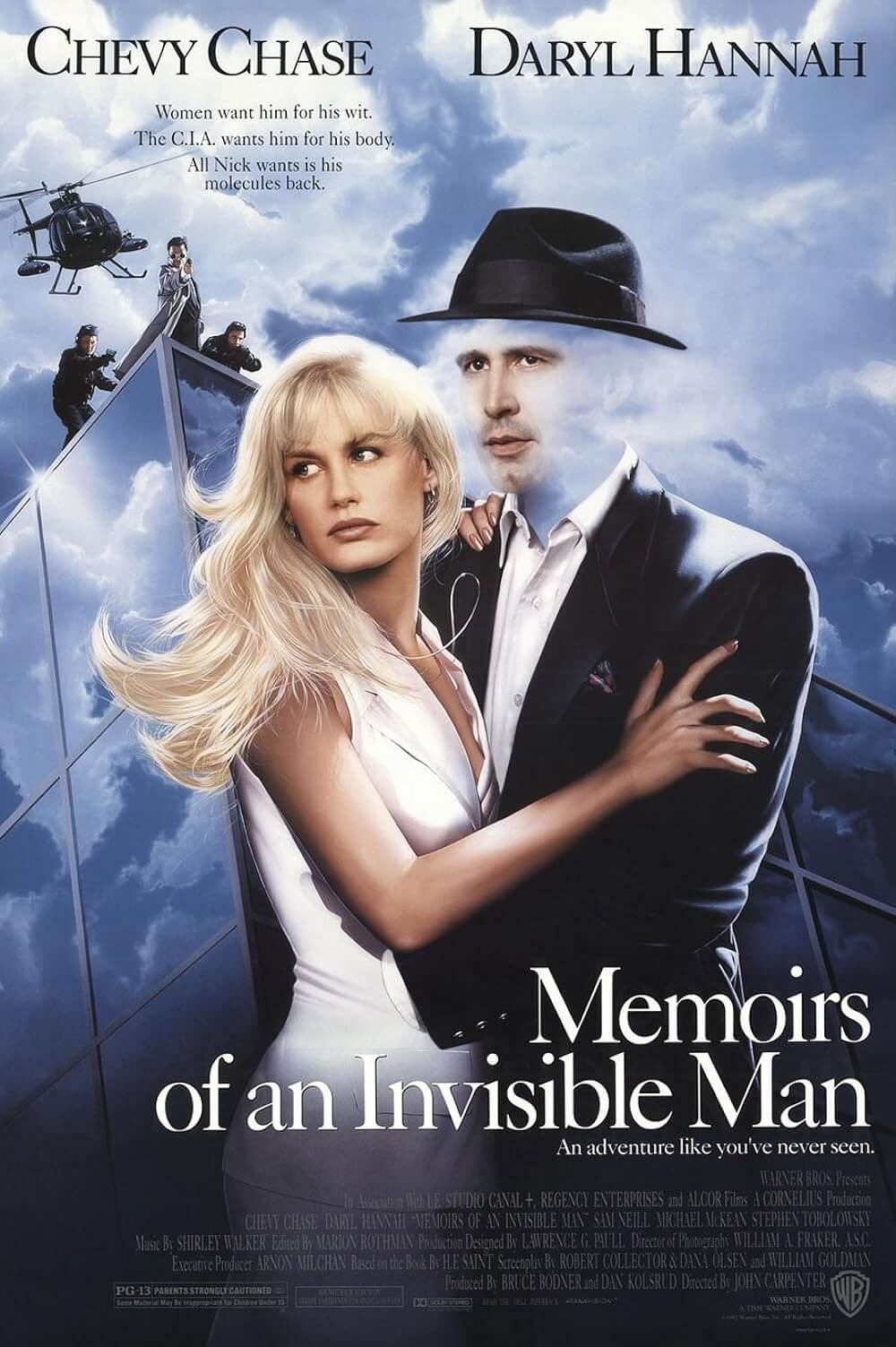

Whannell is tasked with remaking a classic film as well as making a story conceived in 1897 relevant for a modern audience. Aside from the source material, he also has to compete with other, non-Wells invisible man stories—namely, stuff like John Carpenter’s underrated Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992) and Paul Verhoeven’s brainless but visually compelling Hollow Man (2000), films that advanced the special FX used to render invisibility on the big screen. But rather than throwing money at the problem, Blumhouse operates with their usual budget of less than $10 million, forcing Whannell to do more with less. Effectively, Whannell’s film returns Universal’s monster franchise to its B-movie roots (an observation that’s meant as a compliment). The result recalls what producer Val Lewton did in the 1940s with his ultra-low-budget projects like Cat People (1942) and I Walked with a Zombie (1943), relying more on atmosphere, character, and story than elaborate production values. Indeed, The Invisible Man thrives on the idea that necessity is the mother of invention.

From the desperate first scenes, it’s evident that Whannell has reformatted the material from the inside-out, applying a structure reminiscent of Sleeping with the Enemy (1991) that resonates with a contemporary social struggle. It’s the middle of the night, and frightened wife Cecilia must carry out a breathless escape from her controlling, abusive husband Adrian (Oliver Jackson-Cohen), whose modern house reeks of an obsessive, controlling personality and a toxic relationship. Narrowly slipping away in the night with the help of her sister Emily (Harriet Dyer), Cecilia finds refuge with her cop friend James (Aldis Hodge) and his teenage daughter (Storm Reid), though she remains fearful that Adrian will come for her. After a couple of weeks of freedom, Cecilia learns that her husband has committed suicide, though she’s still haunted by the notion that he might have faked his death out of some elaborate scheme for revenge. She’s plagued by an eerie sense that she’s being watched by someone that isn’t there—at least, not that she can see. And when she tries to tell others about what she’s experiencing, they dismiss her claims as paranoia and, worse, come to believe she may be a danger to herself and others.

From the desperate first scenes, it’s evident that Whannell has reformatted the material from the inside-out, applying a structure reminiscent of Sleeping with the Enemy (1991) that resonates with a contemporary social struggle. It’s the middle of the night, and frightened wife Cecilia must carry out a breathless escape from her controlling, abusive husband Adrian (Oliver Jackson-Cohen), whose modern house reeks of an obsessive, controlling personality and a toxic relationship. Narrowly slipping away in the night with the help of her sister Emily (Harriet Dyer), Cecilia finds refuge with her cop friend James (Aldis Hodge) and his teenage daughter (Storm Reid), though she remains fearful that Adrian will come for her. After a couple of weeks of freedom, Cecilia learns that her husband has committed suicide, though she’s still haunted by the notion that he might have faked his death out of some elaborate scheme for revenge. She’s plagued by an eerie sense that she’s being watched by someone that isn’t there—at least, not that she can see. And when she tries to tell others about what she’s experiencing, they dismiss her claims as paranoia and, worse, come to believe she may be a danger to herself and others.

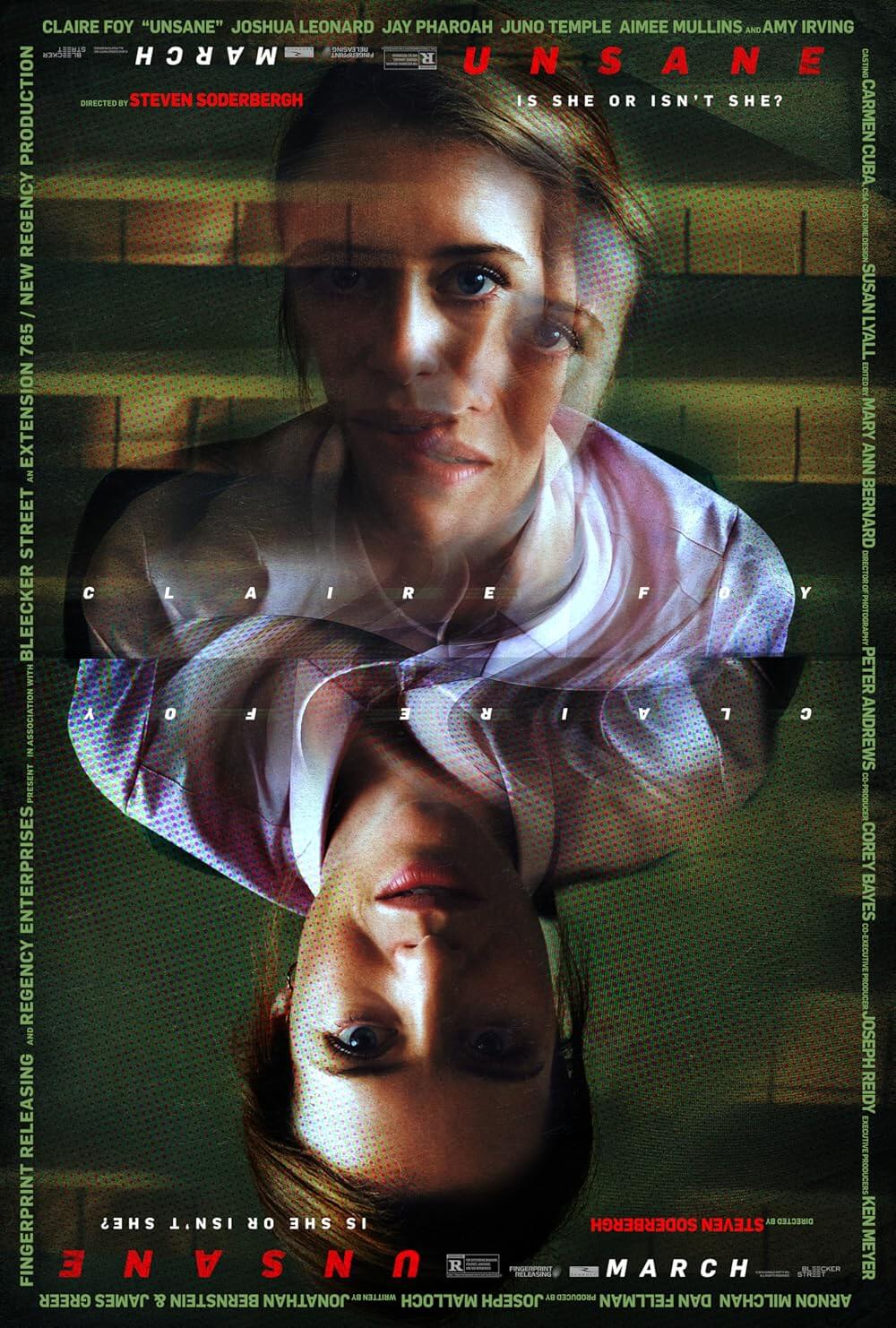

Whannell conceives of a measured pressure-cooker situation, where Cecilia experiences nightmarish, if intangible moments that seem to confirm she’s being haunted by her seemingly late husband, though she’s unable to supply proof to her friends. Adrian, who has faked his own death and wears an invisibility suit to conceal himself, pulls the blanket off Cecilia at night; he sabotages her job interview; he disrupts her personal life to isolate and control her. Whannell shoots these scenes like another Blumhouse supernatural horror yarn, complete with creaky wood floors and Cecilia exploring strange sounds at night. The situation requires Moss to unravel over the film’s 124-minute runtime, delivering a rattled and exhilarating performance that recalls Claire Foy’s journey in Unsane (2018). Much of the film wouldn’t work without a performance of this caliber at the center, as Moss’ desperate, shaken turn distracts from many of the plot holes along the way. Our empathy for the tormented and gaslighted Cecilia supplies an unnerving psychological experience, which makes the eventual scares in the final act, along with its limited touches of CGI, all the more effective.

The Invisible Man’s inspired innovations on the original story have also been woven into its thematic concerns. Whereas Wells’ mad scientist took a drug that made every inch of his body imperceptible, the invisibility suit in Whannell’s version is a clever design of sensors whose appearance may induce a reaction from trypophobics. Here, the invisible man terrorizes his wife by monitoring her every move, though he goes unseen, while his suit is covered with small cameras—a combination that makes him a walking metaphor for the dangers of the male gaze. It’s an approach reflected in how cinematographer Stefan Duscio’s camera often adopts Adrian’s point-of-view, especially in scenes of violence, using a similar body-mounted technique employed on Whannell’s Upgrade (2018). Even as we’re placed in the perspective of the villain, Cecilia, the subject of his constant observation, must find a way to escape his gaze and restore her agency. Whannell’s story brings her to the brink of madness, using more than one gasp-inducing moment that would send anyone to the madhouse, but he finds a satisfying way of making The Invisible Man a story about one woman restoring power over her life.

Whannell has revived material that, just a few years ago under the Dark Universe label, seemed destined to underwhelm. His take on The Invisible Man belongs on a shortlist of superb cinematic remakes—alongside the likes of Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) and David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986)—that completely refashion earlier material with modern-day concerns. And if this Lewton-esque approach is representative of the direction Universal will take on their other properties, more are welcome. Above all, Whannell supplies a satisfying movie-going experience, a film designed to make you grab your neighbor’s forearm in fright. Doubtless, viewers will find nitpicks here and there, but the controlled filmmaking cannot help but induce a powerful reaction. It’s a feat unto itself that Whannell has made this concept genuinely scary again; it’s even better because he made the material feel like an essential story for today.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review