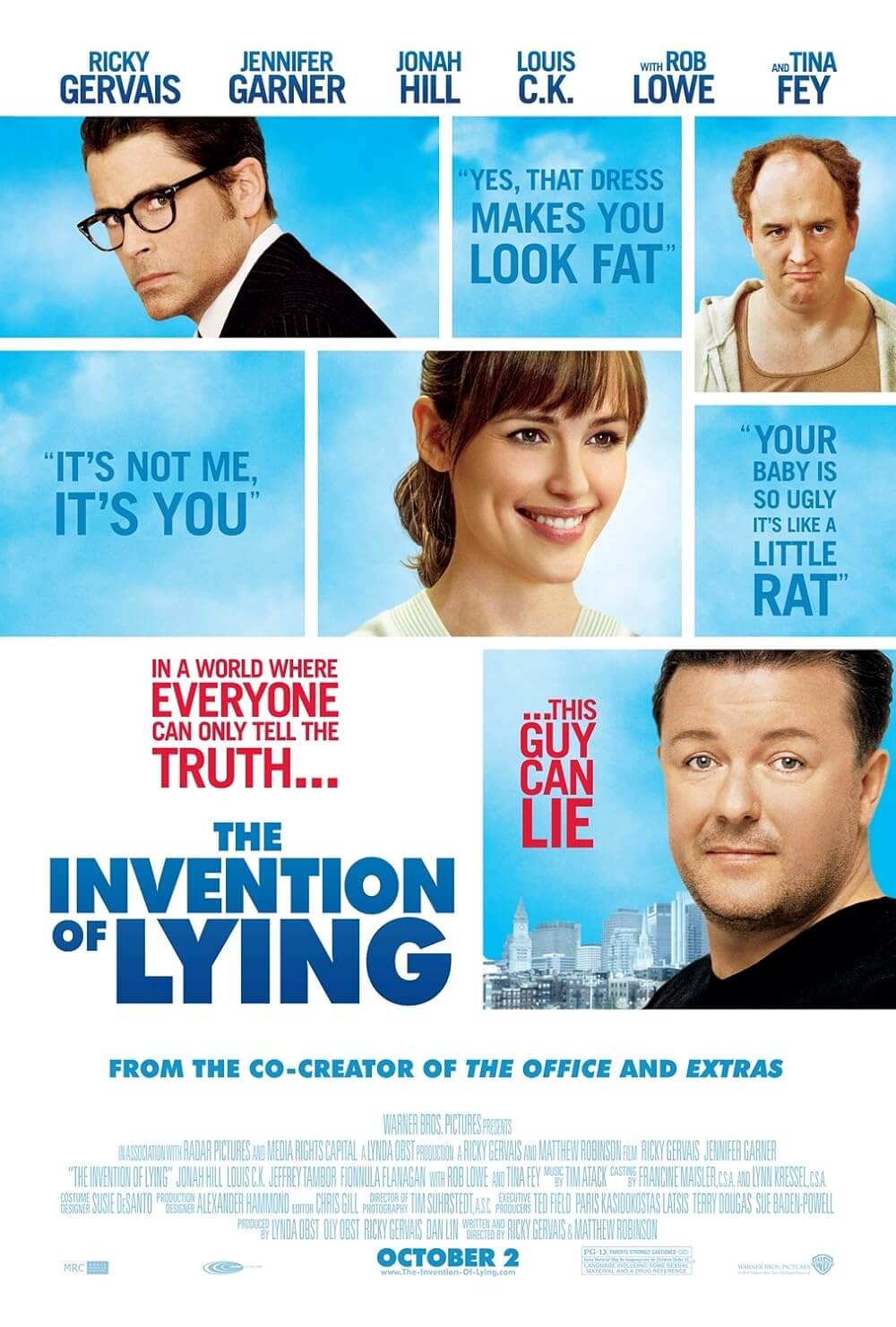

The Invention of Lying

By Brian Eggert |

Ricky Gervais’ ingenious new comedy The Invention of Lying reminds us why we tell lies, if only by demonstrating the brutality of the truth. After all, lies are sometimes told to gain an advantage, but the more common of them are white lies—those we tell to soften the blow of what might be an unfortunate reality. And then there are the lies we tell ourselves; those might also be called delusions. The movie takes place in a very unsympathetic world where everyone tells the truth all the time. The word “lie” doesn’t even exist. The concept hasn’t been conceived until a lowly sad sack realizes there’s nothing to stop him from telling lies and then gaining all the consequent benefits.

That sad sack is played by Gervais, who also co-wrote and co-directed the film with Matt Robinson. It’s not exactly original for Gervais to play another schlubby underachiever, particularly when considering the shallow characters he sometimes inhabits on Extras, Ghost Town, and The Office, except here, he displays such incredible and unexpected humanity. He plays Mark Bellison, a screenwriter who, in this comedy version of a Twilight Zone scenario, writes movies for Lecture Films, the hot studio whose latest release involves a stuffy old reader (Christopher Guest) haranguing about history. But then it’s normal for a film in this world to be 90-minute term paper orations. Mark is assigned to the 13th century, and he’s very unsuccessful since all he writes about is the Black Plague.

You see, with no lies, there’s no such thing as fantasy or metaphor, no need to dilute the truth with our typical Hollywood escapism. They call retirement homes “A Sad Place for Old Hopeless People” and one advertisement reads, “Pepsi … when they don’t have Coke.” What’s worse, people don’t censor their thoughts, so someone like Mark has a hard time with life. When he arrives for a blind date with Anna (Jennifer Garner), he’s greeted with looks of disappointment. Right away, she flat-out tells him that she’s pessimistic about their date. He’s overweight, clearly a loser, and she has no intention of sleeping with him. And they could never get married because he’s an inappropriate genetic match—their kids would all be chubby and have snub-noses. But she goes along with the date anyway, out of politeness.

After being summarily rejected, fired, and then evicted from his apartment, Mark breaks down at the bank. But something clicks in his brain, and suddenly, he’s the only person in the world who can tell lies—he convinces the bank teller that there’s actually $800 in his account, not the $300 that her records show. Whoops, our mistake. Here’s your $800, sir. In addition to not telling lies, the people in this world haven’t evolved a sense of doubt. There’s no need. Predictably, Mark uses his new gift of lying to attain money and celebrity. He gets his job back at work by conceiving of the 13th century’s forgotten history, wherein aliens, ninjas, and robot-dinosaurs coalesced.

Where Gervais’ satire really comes to fruition is a touching scene where Mark’s mother dies. On her deathbed, she worries about fading into nothingness. Mark spins her yarn to make her happy in her last moments. He tells her there’s a place everyone goes after they die, where everyone gets their own mansion, all your friends are there, and there’s free ice cream for everyone. Word gets out about this hereafter Mark speaks of. Everyone around the globe wants to know about it. The film’s funniest sequence involves Mark standing on his doorstep, and having written the afterlife’s rules on two tablets (i.e. pizza boxes), he reads about The Man in the Sky and the rules of getting into The Good Place or The Bad Place. No one in the crowd understands this Man in the Sky’s intentions, why He does some wonderful things and some terrible things. It doesn’t make much sense. In his realist, atheistic viewpoint, Gervais acknowledges how religion was created to make people handle the harsh realities of life a little easier. But he also recognizes that people who don’t know any better will go along with whatever you tell them.

What a sophisticated comedy this is, even though the central plot involves Mark wooing Anna and convincing her that love is blind. The scenario contains all those typical romantic-comedy tropes, including a big wedding finale where Mark storms-in to rescue Anna from marrying the film’s resident jerk (played by Rob Lowe). But it transcends those clichés through its environment of truth-tellers. Each gag points out how absurd and petty our reality remains for relying on dishonesty so much. The only major criticism would be the limited scope of the film which leaves questions: Do politics and wars even exist in this world? Mark tells everyone they have three strikes before they go to The Bad Place, so does that mean everyone can have two free strikes? Are people going about and committing two murders or two robberies and thinking they can still go to The Good Place? These are questions that might be answered in a longer movie, a sequel, or a television series set in this world.

Backing Gervais are a succession of supporting roles and cameos filled by notable comedians and actors—Edward Norton, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Jason Bateman, Louis C.K., Martin Starr, Tina Fey, and Jonah Hill all make hilarious contributions. Through the hearty laughs, The Invention of Lying becomes instantly original and at times ingenious for purporting moral and social discourse, as through the guise of a typical rom-com it confronts the audience with the very core of their beliefs and behaviors. Without stepping over the line and becoming offensive to even the most sensitive viewer, the film makes smart observations but never ceases to be endearing. This is all further confirmation that Gervais’s brand of inventive humor shows no signs of losing its edge and that he’ll continue to be one of the funniest comedians around.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review