The Impossible

By Brian Eggert |

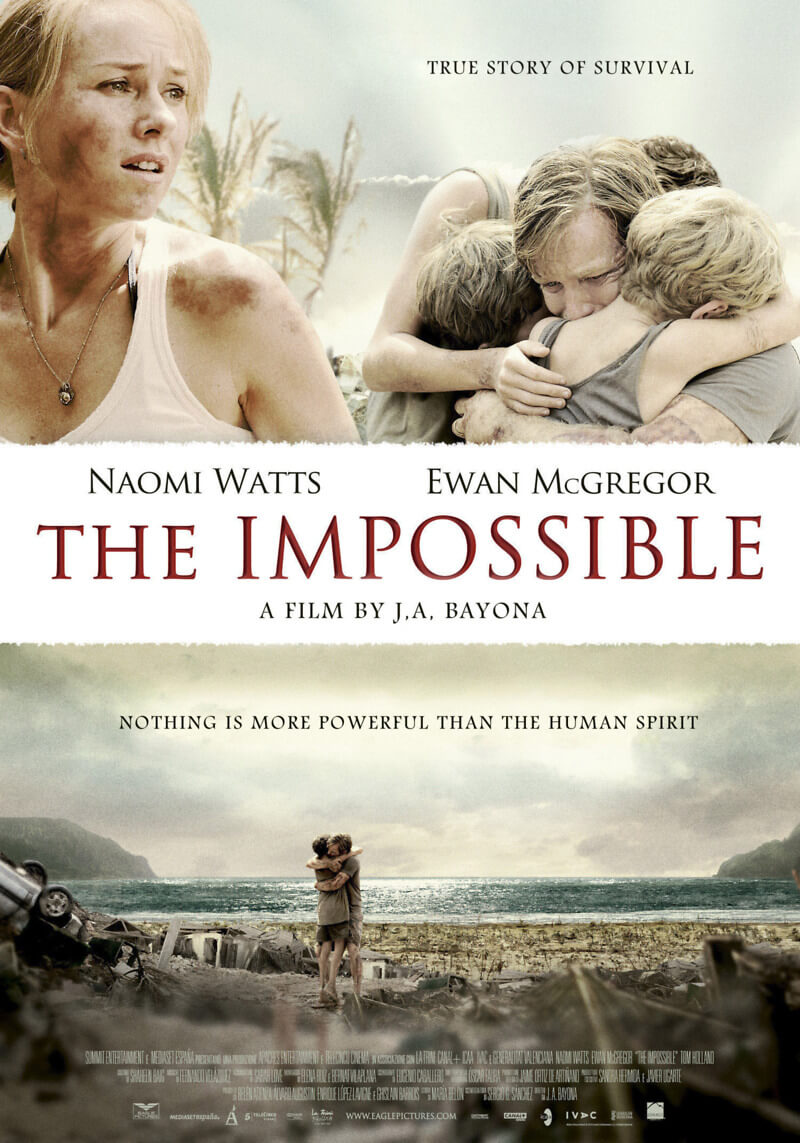

Far removed from Hollywoodized disaster movies like Dante’s Peak, The Poseidon Adventure, and a whole slew of Roland Emmerick flicks, The Impossible is an emotionally exhausting true story of survival. Concerning the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake that resulted in a tsunami, which then washed over southern Asia and left nearly 300,000 people dead or missing, the film details the catastrophe in the same manner Steven Spielberg handled his War of the Worlds remake—through the prism of one family’s story. Indeed, Spanish helmer Juan Antonio Bayona has reached a Spielbergian level of technical mastery and emotionalism here, his film both sentimental and epic in just the right crowd-pleasing ways. It’s a terrifying and draining experience from start to finish, and it’s made with such a staggering degree of humanity that one would have to have a heart of stone not to feel something profound during its runtime.

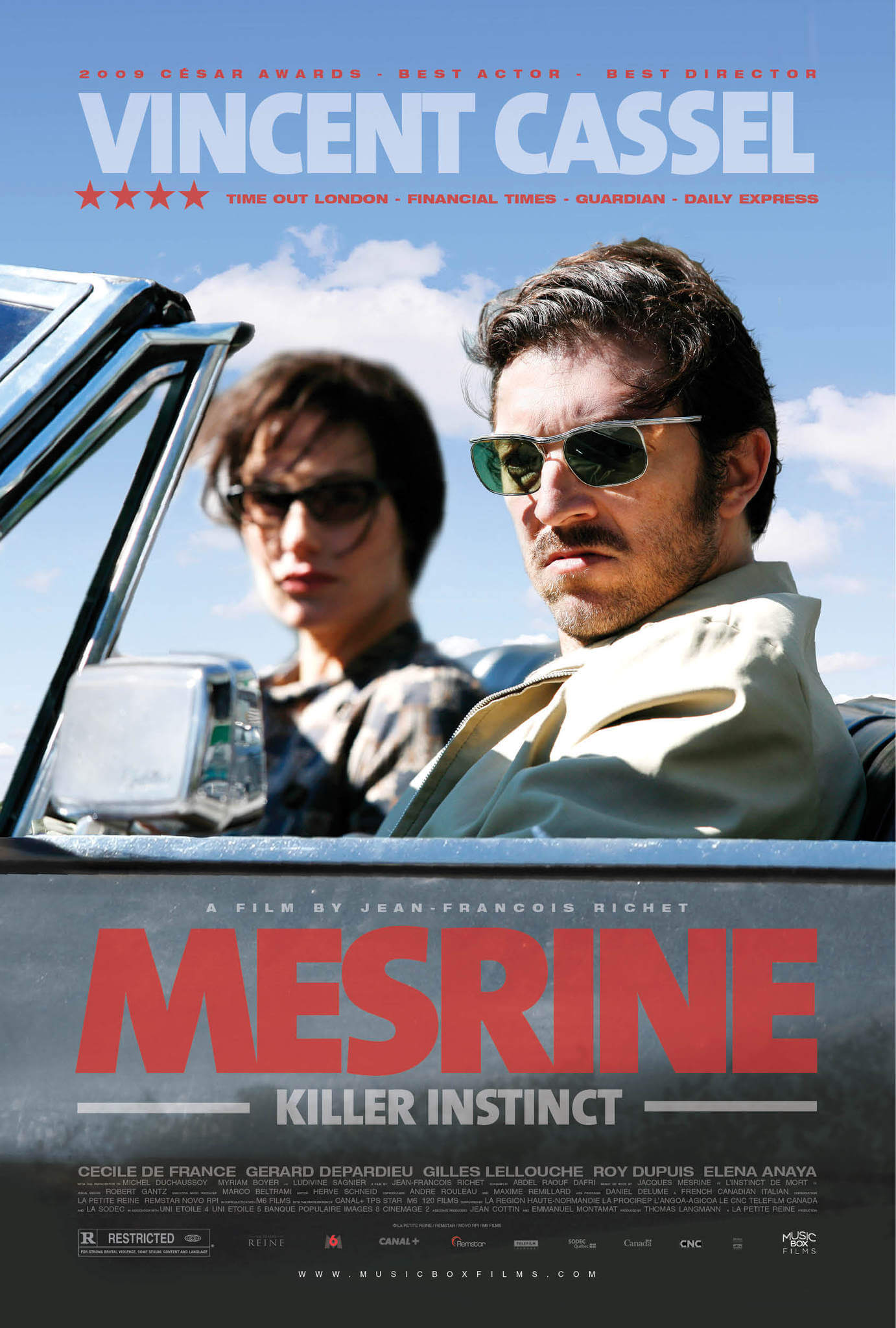

Based on the true story of a Spanish family, the screenplay by Sergio G. Sanchez alters their nationality into a British family vacationing in Thailand. This Anglo-ization of the characters no doubt broadens the commercial appeal, but it brings into question the authenticity of the screen story. At any rate, for the first fifteen minutes, Bayona creates an unbelievable amount of tension through brooding shots of the ocean, as though we were looking into a dark closet where some monster lurks. Bayona and Sanchez, the talented team who made their debut with 2007’s creepy The Orphanage, know how to create a sense of dread. Early scenes between the happy family—father Henry (Ewan McGregor), mother Maria (Naomi Watts), and children Lucas (Tom Holland), Simon (Oaklee Pendergast), and Thomas (Samuel Joslin)—slowly become agonizingly suspenseful as the ocean looms in the background. In a few moments, a 100-foot wave comes crashing through their picturesque resort, resulting in a sequence that dwarfs Clint Eastwood’s intense tsunami rush in Hereafter.

About three times as long and infinitely more powerful than Eastwood’s, Bayona’s tsunami sequence seamlessly integrates practical and computer-generated effects, including a massive Spanish water tank and actual Thailand locales, to recreate the maelstrom. We see bodies tossed about and struck with debris, rolling underwater by the force of the waves. In the chaos, Maria and her oldest son Lucas are separated from the others. After the flooding subsides, the badly injured Maria guides Lucas through the wreckage, limping and losing blood but determined to save her son. With the help of some local Samaritans, they make their way to a hospital, where Lucas spends his time reuniting family members separated by the calamity. Maria waits on her makeshift bed for the busy hospital staff to get to her. Both Maria and Lucas believe Henry and the younger siblings have been lost. But back at their vacation resort, Henry and the two other children have survived.

Much suspense and cinematic finesse is applied in the finale, where the family all arrives at the same destination but have yet to find one another. Quite manipulatively, Bayona takes liberties with the original story to extend these emotions as long as possible, making the eventual reunion all the more overwhelming. Even though we know we’re being worked over in sort of a silly way, the power of the performers and the clarity of the subjective camerawork refuse to let us feel removed from the moment. Watts, who earned an Oscar nomination for her performance, communicates physical and motherly distress with a shocking level of devotion. McGregor has at least one standout scene when he breaks down in front of others during a brief phone call home. Most impressive is young Holland, an inexperienced actor who looks something like Jamie Bell and has that actor’s intensity and range to boot.

Wisely, Bayona avoids limiting his scope to one family, occasionally pulling back for a panoramic view of the ruined landscape or the overstuffed hospital teeming with needy patients. We get a sense of the widespread devastation without getting too off-subject by exploring other characters outside the family. Yet, the director resists typical disaster movie clichés by refusing to include prolonged exposition about what happened and why, typically shown by background newscasts. It’s enough that we understand the basic fears and joys felt by those onscreen. The Impossible is a punishing experience, with hardly a moment after the first twenty minutes where a lump isn’t in your throat or tears welling up in your eyes. Bayona’s direction is thoughtful and tremendously realistic in its depiction of the tsunami, its after effects, and the human spirit that was tested by it. Unique for a film of this kind, it’s less about the catastrophe than the humanity and courage that it inspired.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review