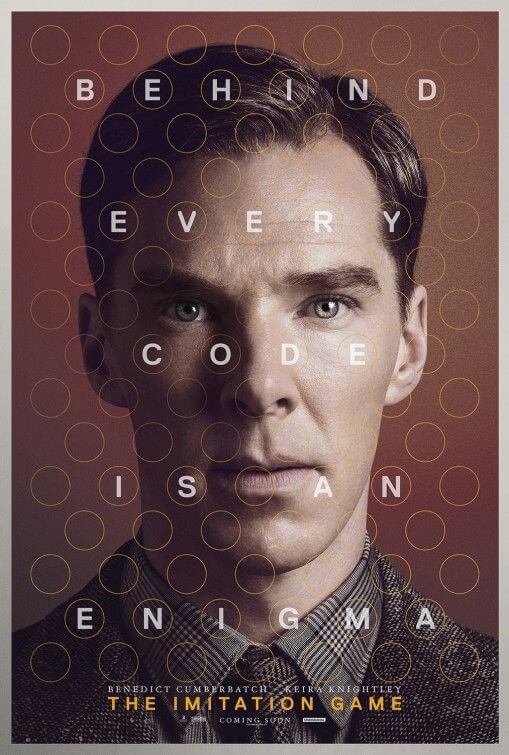

The Imitation Game

By Brian Eggert |

A potent wartime drama and tragic human rights tale, The Imitation Game puts Benedict Cumberbatch in another role as an eccentric genius who looks at the world from a unique perspective. After stunning millions of fans and maintaining cultish following of “Cumberbitches” with his turn as the modern Sherlock Holmes on BBC’s popular Sherlock television series, he realizes an award-worthy portrayal as Alan Turing, the ostensible father of artificial intelligence who cracked Germany’s Enigma code machine and in turn helped win World War II. Beyond building the first computer, Turing was also a victim of Britain’s cruel Labouchere Amendment of 1885, which considered homosexuals like himself indecent and therefore subject to criminal reeducation. This fascinating and many-textured subject matter comes to life as certain Oscar bait in the film from Norwegian director Morten Tyldum (Headhunters) and distributors at The Weinstein Company. This early review comes after a screening at the Twin Cities Film Fest, where the audience received it with much applause and enthusiasm.

First-time screenwriter Graham Moore broaches his topic through the framing device of a police investigation in 1951. After Turing’s home is ransacked, a detective (Rory Kinnear) hauls him in as a suspected Russian spy, but it’s really his homosexuality Turing is trying to hide. He tells his life story, which skips between his early days exploring cryptography and young love as a confused and Asperger’s-like schoolboy. Later, scenes in 1939 find him applying for a top-secret position at Hut 8 at Bletchley Park, where the British government has engaged a handful of mathematicians to crack Engima’s seemingly unbreakable code—with its some 159 million million million variables that reset every day at midnight. Each day, dozens of Nazi orders go out encrypted; if they can be deciphered, Allied forces would have a decided advantage. The project’s blimpish military administrator Commander Denniston (Charles Dance) and his chess whiz golden boy Hugh Alexander (Matthew Goode) are determined to decrypt by standard methods, whereas Turing knows their approach would take decades.

An unsociable prodigy who has no time or inclination to explain himself to people of lesser intelligence, Turing proposes to build a machine that can tick through Enigma’s coded possibilities within the day-long window, and with much satisfaction he circumvents his doubters by personally writing Winston Churchill, who in turn puts Turing in charge of the entire project. Structurally, Moore’s script borrows heavily from Aaron Sorkin’s outline for The Social Network, focusing on Turing as a genius mind devoid of social skills and held back by his often humorously condescending superiority. He’s a character on the margins, where something as simple as ordering him lunch becomes a challenge for his coworkers. But his all-male think tank at Bletchley Park is given an auspicious feminine perspective when Turing hires Joan Clarke (Keira Knightley), a talented codebreaker and college-educated woman. Together, Turing and Joan find a common ground in that they’re both outsiders and too smart to fit in; and they might be a great couple if Turing leaned that way. Alas, they’re engaged in an appearances-only arrangement.

The fim is quick to remind us, “Sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.” This line is repeated to a rather schmaltzy effect three times throughout, applying it thick for general audiences. Whether it’s referring to Turing’s intelligence, Joan’s femininity, or his later-exposed homosexuality, the theme doesn’t need to be spelled out in such broad terms. Meanwhile, the film washes over the technical aspects of how Turing’s eventual machine, dubbed “Christopher” after his first love, functions. Though the majority of The Imitation Game’s audience may not have understood a more detailed explanation, the fascinating part of a character like this is that he can speak endless technobabble and impress us with his big brain. Instead, Turing’s machine stands for itself—a jumble of wires and knobs clicking away. Nothing so complicated could be anything but brilliant, the film seems to be saying. Never mind how it works. At least Moore’s script, based on Andrew Hodges’ book Alan Turing: The Enigma, has more historical relevance than Michael Apted’s film Enigma (2001), starring Dougray Scott and Kate Winslet, which told author Robert Harris’ loosely historical account of Turing’s influence on WWII in a bland thriller.

Tyldum does, however, cut away to scenes of wartime destruction to remind the audience of the stakes. What becomes most fascinating is how the British government resolves to use Turing’s machine after they discover it works; rather than stopping every German plane or boat whose course is intercepted from Enigma, they must strategize over which targets will help them win the war, but without giving away to the Nazis that Enigma has been decoded. This is one of the most fascinating aspects of Turing’s story, and yet it’s barely explored. Perhaps such details were overlooked to broaden the dramatic strokes and lessen historical details—again, for accessibility’s sake. After all, much of The Imitation Game plays like a character study more than a historical account. We see harrowing scenes of Turing, a skilled long-distance runner, working out his day’s endless frustrations through a run; elsewhere, he toils assiduously on “Christopher”. Cumberbatch’s portrayal is the film’s brilliant centerpiece, filled with arrogance and vulnerability, and he’s wonderfully textured throughout, particularly in later scenes. Though he may seem at risk of becoming typecast as such maligned, eccentric masterminds as Sherlock or his upcoming role in Marvel’s Dr. Strange, the actor manages to incorporate an impressive degree of variation from one such role to the next.

Queen Elizabeth granted Turing a posthumous pardon for his so-called crimes in 2013, and The Imitation Game does a fine job of making Turing’s life story accessible for mass consumption—arguably to a fault, since his sexuality is more a concept than a reality shown onscreen, with any physical realization of Turing’s homosexuality conspicuously avoided. Nevertheless, Tyldum has put together a professional production that looks gorgeous thanks to cinematographer Oscar Faura (The Impossible) and production designer Maria Djurkovic (Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy) and has been lovingly scored by Alexandre Desplat. And while Knightley and Goode give impressive supporting performances, the film is a Cumberbatch affair. Noted objections about the standard handling and thematic transparency won’t prevent anyone from savoring the engaging subject, nor will they spoil any overall appreciation for its narrative rewards and impressive central performance.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review