The House That Jack Built

By Brian Eggert |

Lars von Trier’s latest cinematic provocation, The House That Jack Built, arrives with a host of punishing images and themes designed to stimulate his audience one way or another. With his gristly, didactic tale of a serial killer, the Danish filmmaker seeks to justify his sometimes unpopular personal and artistic choices by arguing his case with an unsubtle metaphor, while remaining all-too-aware that his arguments and methods will be used against him—to the extent that this awareness becomes, tediously, part of the film. As von Trier goads his audience into a reaction, he doesn’t seem to care whether that reaction is unabashed praise from his devoted cinephiles, who are perhaps too quick to defend whatever von Trier does given its aesthetic merits and authorship, or the disapprovals from critics, who have grown tired of the director’s antics. Love or hate, that’s what von Trier wants; polarized reactions fulfill his narcissistic need for attention. And yet, his games have grown tiresome and predictable over the years, leaving The House That Jack Built nothing to love or hate, but merely something to shrug off as yet another Lars von Trier film.

After a divisive premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, IFC has released The House That Jack Built stateside in a two-and-a-half-hour R-rated cut, somewhat trimmed from the original unrated “director’s cut” version, which will debut on digital platforms in mid-2019. The Cannes screening surprised many, not only because the material clearly aims to shock with its depictions of horrific violence, but because Cannes festival director Thierry Fremaux had banned von Trier in 2011, declaring him “persona non grata” after the director compared himself to Adolf Hitler and then alluded to himself as a Nazi. It’s even more surprising since The House That Jack Built seems to reference his encounter at Cannes by inserting Nazi imagery and making references to their powerful use of iconography. Watching the film with this in mind, it’s as though he incorporates his original arguments into the proceedings to prove that today nothing is sacred—that people like himself or, say, Donald Trump, who he has censured in interviews, can increasingly lower the bar, and people will allow themselves to be lowered. The indifference of the world is a theme that crops up throughout The House That Jack Built. But delineating the lowest depths of free artistic expression just because you can isn’t exactly a noble enterprise, and doesn’t help improve the conditions that he seeks to critique.

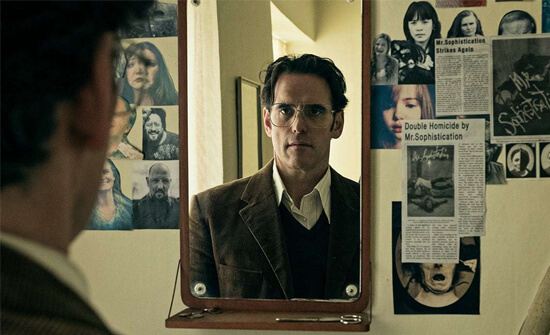

The House That Jack Built takes on an episodic structure in which the titular serial killer, played by Matt Dillion, confesses his crimes and debates their artistic merits with someone named “Verge” (Bruno Ganz), whose presence is merely a voice at first. The self-aware setup is a reference to The Divine Comedy, with Ganz as Virgil, which would make Dillion a stand-in for both von Trier and Dante. (The less said about the egoism of an artist comparing himself to a timeless poet, the better.) Similar to Dante’s epic poem, Jack’s existence is a hellish one and, like von Trier, he views life as an interplay of infernal human interactions and artistic creation. Jack sums up his experiences as a killer in five “Incidents,” each selected to reveal another aspect of his personality and build his arguments about the world. The structure recalls that of Nymphomaniac (2014), where Charlotte Gainsbourg’s sex-addicted protagonist tells her life story to Stellan Skarsgård’s nonjudgmental listener. Both Ganz and Skarsgård’s characters suggest there’s nothing the confessor could say that would startle, offend, or dismay—they’ve heard it all before. Is this how von Trier hopes his audience will engage with his films, with the removed intellectualism of Verge? I think not, since the director seems to delight in pushing boundaries of taste as a demonstration of his right to do so. And if he does yearn for intellectual distance, reaching for the mind over emotion is a low artistic ambition.

Of the five killings that Jack recounts to Verge, four of them occur against women. In the first episode, Jack stops to help a woman (Uma Thurman) having car trouble. She’s a disagreeable, insulting woman, and she repeatedly taunts him about how he looks and behaves like a stereotypical serial killer—then adds, “You’re way too much of a wimp to murder anyone.” It’s as though she’s asking for it, von Trier suggests. Faced with such a contemptuous woman, Jack asks, “Why is it always the man’s fault?” in a line that seems designed to feed accusations of von Trier’s misogyny. Then, compelled to it, Jack caves her face in with a tire jack. Perhaps Jack should be asking himself why he drives around in a large van suitable only for transporting a garage band, a gang of 1970s cartoon detectives, or serial killers.

Of the five killings that Jack recounts to Verge, four of them occur against women. In the first episode, Jack stops to help a woman (Uma Thurman) having car trouble. She’s a disagreeable, insulting woman, and she repeatedly taunts him about how he looks and behaves like a stereotypical serial killer—then adds, “You’re way too much of a wimp to murder anyone.” It’s as though she’s asking for it, von Trier suggests. Faced with such a contemptuous woman, Jack asks, “Why is it always the man’s fault?” in a line that seems designed to feed accusations of von Trier’s misogyny. Then, compelled to it, Jack caves her face in with a tire jack. Perhaps Jack should be asking himself why he drives around in a large van suitable only for transporting a garage band, a gang of 1970s cartoon detectives, or serial killers.

The second episode finds Jack awkwardly talking his way into a widow’s (Siobhan Fallon Hogan) house after promising to increase her pension. The strangulation and stabbing that follow reveal Jack’s obsessive-compulsive tendencies in a rare moment of sardonic humor, causing Jack to repeatedly return to the house to check in absurd places for blood spots he might have missed behind framed pictures or under chair legs. Jack’s OCD is a recurring motif, indicated by the hundreds of frozen pizzas he invested in with plans to resell, though now they’re carefully organized in his walk-in freezer—where he stores the bodies of his victims. Each new murder is a victory over his OCD, he says, but it’s also a work of art. The third “Incident” details how Jack brought a woman (Sofie Gråbøl) and her two young sons out to his wilderness hunting grounds, where he tortures them before turning them into the dismembered pieces of an art installation. Indeed, Jack equates murder with art, specifically architecture, and he considers himself an engineer of murder.

The film’s nasty streak of violence against predominantly women comes to a head in the fourth “Incident,” where he taunts a woman about the indifference of the world. This woman, with whom Jack has supposedly almost fallen in love, has been nicknamed “Simple” (Riley Keough) by Jack, an insult he uses to berate her intelligence. Before slicing off her breast and killing her, he invites her to scream and beg for help in an apartment complex, knowing that neither the neighbors nor authorities will come to her rescue. Although Verge is quick to point out that each of the “Incidents” shared involve women, Jack claims he’s an equal opportunity killer of both men and women, despite recounting only the “stupid women.” The current of misogyny in The House That Jack Built is a topic of debate within the film, but it’s less debatable for the viewer, and the effect extends beyond the screen. Since the emergence of the #MeToo movement, von Trier’s treatment of women, both on and off-screen, has been brought to the forefront of the conversation about his cinema. Björk and Nicole Kidman have both admitted to his inappropriate and unprofessional conduct while in production, and such allegations unavoidably lead to parallels of misogynist themes and behaviors in his work.

As if to contradict this line of thinking, the fifth “Incident” is a mass killing of six people, focused largely on a man. Von Trier is a smart and self-conscious filmmaker, in that he’s aware of his status within the film community, the downfalls of his persona, and how others perceive him. He uses this knowledge to equip his film with a counter-argument, making The House That Jack Built a text through which the viewer can discuss the director’s favorite subject: himself. Throughout the film, one suspects that von Trier has constructed it as a reaction to those averse to his body of work, those who equate his films to mere provocations—as if processing art was merely an intellectual or logical exercise. He’s creating a film in which audiences see a character that will be perceived in the way he believes he’s perceived by critics. But he also anticipates the backlash that might meet such a text, having dealt with backlash before. This is handled with such infallible cleverness that it cannot help but incite suspicion. No wonder Jack has personified his murderous impulses and calls them Mr. Sophistication—a name that underscores von Trier’s at once self-hatred and unchecked ego.

As if to contradict this line of thinking, the fifth “Incident” is a mass killing of six people, focused largely on a man. Von Trier is a smart and self-conscious filmmaker, in that he’s aware of his status within the film community, the downfalls of his persona, and how others perceive him. He uses this knowledge to equip his film with a counter-argument, making The House That Jack Built a text through which the viewer can discuss the director’s favorite subject: himself. Throughout the film, one suspects that von Trier has constructed it as a reaction to those averse to his body of work, those who equate his films to mere provocations—as if processing art was merely an intellectual or logical exercise. He’s creating a film in which audiences see a character that will be perceived in the way he believes he’s perceived by critics. But he also anticipates the backlash that might meet such a text, having dealt with backlash before. This is handled with such infallible cleverness that it cannot help but incite suspicion. No wonder Jack has personified his murderous impulses and calls them Mr. Sophistication—a name that underscores von Trier’s at once self-hatred and unchecked ego.

My own relationship with von Trier films began with admiration for his 1990s and early 2000s output (Breaking the Waves, Europa), and it has since resulted in sustained indifference. His recent string of visually sublime, narratively bleak efforts, labeled his “Depression Trilogy,” have each kept me at a distance. Watching Antichrist (2009), Melancholia (2011), and Nymphomaniac, it’s impossible not to admire their purely aesthetic merits. In The House That Jack Built, von Trier’s use of form, as always, is impeccable. He often draws impressive ensembles to give raw, uncompromising performances, and the cast here is no exception. Dillon gives his best performance in decades, managing a range of horrific and comic moments. However, occasionally the performance is unintentionally funny when Jack and Verge dissect the killer’s psyche with psychobabble that explains away his actions as a desire for love. No amount of superior acting prevents the absurdity of such lines from leaking out.

Visually, the director captures images that prove well-composed, even beautiful. For instance, his recreation of Eugène Delacroix’s painting The Barque of Dante (1822) is sublime in every sense of the word. Elsewhere, he employs animations, wildlife footage, clips from his own films, stock footage, grainy digital photography, varying aspect ratios, and occasional cutaways to Dillion standing in an alley, holding white cards with black letters à la Bob Dylan in Don’t Look Back (1967)—or, if you prefer, the INXS video for “Mediate.” The House That Jack Built is never a dull experience, formally speaking, although the consequence of its conceptual mannerism is tedious. Manuel Alberto Claro uses a variety of cameras, aspect ratios, and video sources, and it’s all assembled by the editors (Molly Malene Stensgaard, Jacob Secher Schulsinger) with an undeniable urgency. It helps that, throughout, David Bowie’s “Fame” dominates the soundtrack, though it’s a vapid reminder that Jack views himself as a celebrity of sorts, even if it’s only in his own mind.

Beyond the social and ethical questions of supporting such an artist—whose relationship with his fellow filmmakers may perpetuate a culture of toxic masculinity, whose films indulge and sustain his own narcissism—there’s the question of the art itself. The question aesthetic theorists often ask to determine the value of an artwork is whether it successfully evoked emotion. Herein lies the primary failing of The House That Jack Built and, further, many of von Trier’s recent films. He’s so concerned with pushing the limit and confronting the audience that it stops being an emotional experience and instead becomes a philosophical and intellectual one. We’re trying to figure out von Trier’s artistic goals rather than experience the art on an emotional level. Note the long passages in the film in which Jack explains his elaborate mental processes. He describes his manic transitions from the highs and lows of pleasure and pain between murders like a man walking between street lamps at night, and von Trier illustrates this process with a cartoon that reminded me of the Scott Free logo. This sequence is just one example of a possible many in the film where Jack and Verge engage in a dramatically inert discussion of the killer’s impulses, robbing the experience of any emotional resonance.

Beyond the social and ethical questions of supporting such an artist—whose relationship with his fellow filmmakers may perpetuate a culture of toxic masculinity, whose films indulge and sustain his own narcissism—there’s the question of the art itself. The question aesthetic theorists often ask to determine the value of an artwork is whether it successfully evoked emotion. Herein lies the primary failing of The House That Jack Built and, further, many of von Trier’s recent films. He’s so concerned with pushing the limit and confronting the audience that it stops being an emotional experience and instead becomes a philosophical and intellectual one. We’re trying to figure out von Trier’s artistic goals rather than experience the art on an emotional level. Note the long passages in the film in which Jack explains his elaborate mental processes. He describes his manic transitions from the highs and lows of pleasure and pain between murders like a man walking between street lamps at night, and von Trier illustrates this process with a cartoon that reminded me of the Scott Free logo. This sequence is just one example of a possible many in the film where Jack and Verge engage in a dramatically inert discussion of the killer’s impulses, robbing the experience of any emotional resonance.

Those who defend The House That Jack Built and von Trier often lash out at critics who deride his work, claiming those who don’t acknowledge that this is the work of a master have clearly missed the point or simply fail to see his genius. So it’s with a certain von Trierian maneuver that I emphasize my admiration for the director’s formal luster and acknowledge that, yes, von Trier is a masterful filmmaker. Obviously, I wouldn’t write this long of a review about vacuous, inane filmmaking devoid of artistic merit. It’s precisely because I see the merits of his form that I find its overly mindful digressions into self-indulgence tiresome. I don’t think that The House That Jack Built goes too far, as some other critics have claimed. Rather, I find that his increasingly petulant need to make every film about his own relationship with his audience and critics has resulted in an auteur who has stopped telling stories and instead has rested on himself as subject matter. As an artist, he’s in a state of arrested development. It’s a banal perspective that he’s adopted, and one hopes that someday Lars von Trier will resolve to tell stories about something other than Lars von Trier.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review