The Hole

By Brian Eggert |

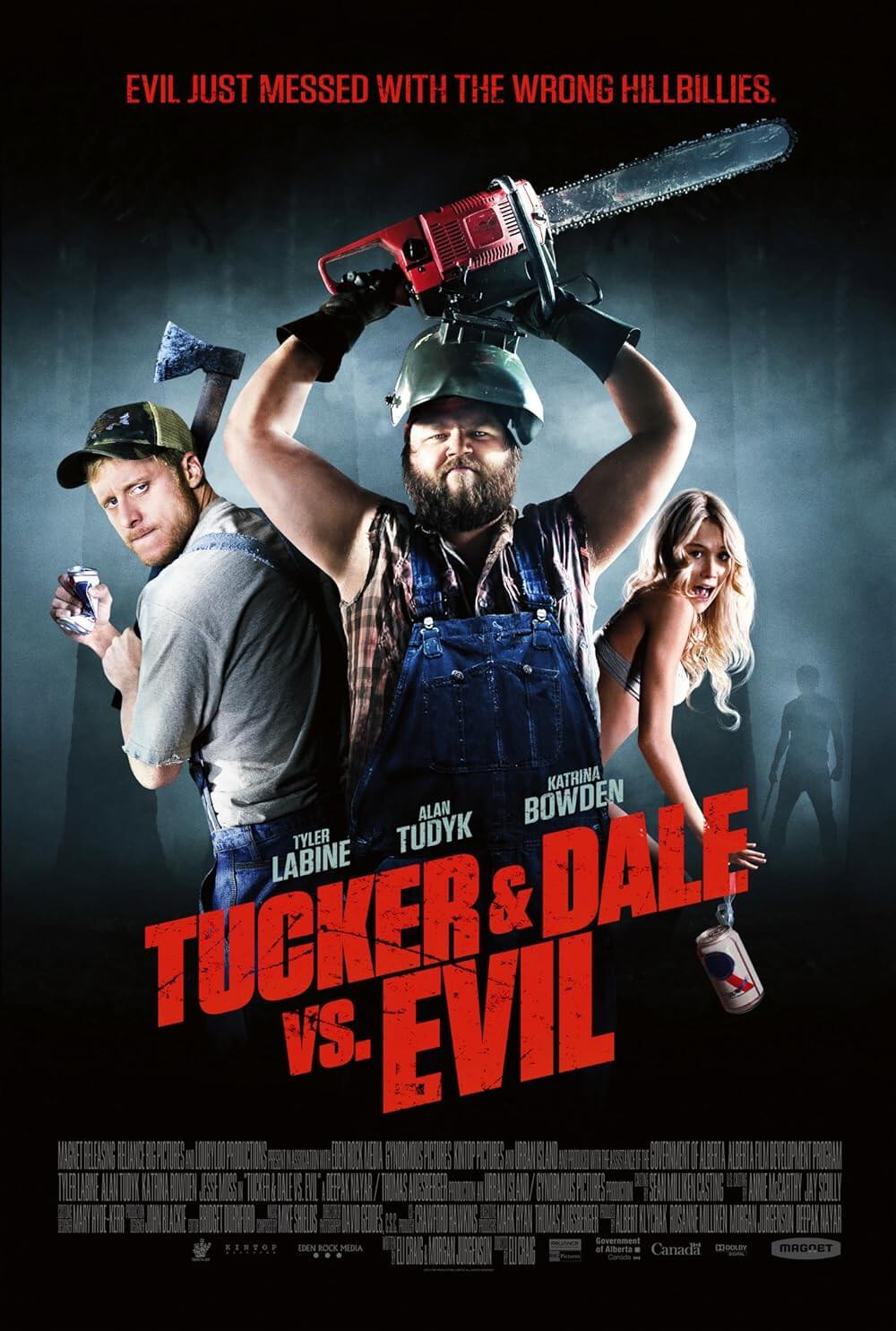

Not since the 1987 cult hit The Monster Squad has there been a youth-oriented horror-comedy on par with Joe Dante’s The Hole, a film whose believable characters and surprising, relatable themes outweigh its cheap PG-13 thrills. Shot in 2008 and released in Europe in 2009, the film’s long-delayed stateside release comes with a minor theatrical push followed by a larger home video and on-demand market debut. Had it been released twenty years ago during Dante’s heyday of Gremlins and Innerspace, the film might be a cult classic by now. But in the decades following the eighties, Dante’s career slowly declined, and ironically enough, he’s back to where he started: making low-budget horror movies (his first major release was the Jaws ripoff Piranha) with airs of fun and ingenuity embedded into every frame.

Mark L. Smith’s script adopts a familiar Dante theme, where a family from the city moves into a suburban neighborhood and finds evil lurking in their basement. Teenager Dane (Chris Massoglia) and younger brother Lucas (Nathan Gamble) struggle to acclimate to their new surroundings, while their single mother (Teri Polo) hurries back to work. Left at home, where they spark a friendship with neighbor Julie (Haley Bennett), a girl about Dane’s age, the youngsters stumble upon a closed wooden hatch in their basement. Secured with multiple padlocks, the door is clearly meant to stay closed, but being naïve, they search for the keys and find that under the door resides a bottomless pit. And as they look into this abyss, it does indeed look back at them. When they probe the former homeowner, Creepy Carl (Bruce Dern), for answers, he explains that any who gazes into the hole will find their worst fears realized.

Made on a shoestring budget, the film’s special effects sometimes appear rather wonky. An editing effect meant to make an underworld girl look like something out of 13 Ghosts or Silent Hill is a bad imitation of the real thing, while the digital shots are at the level we expect from contemporary, low-budget horror. Although filmed for 3D, the American distributors have failed to make this feature available for either a theatrical or home theater 3D experience, and so this critic cannot comment on Dante’s use of the device. Still, a few scenes were noticeably engineered for 3D audiences, such as Lucas tossing a baseball up in the air, and a bird’s eye view camera angle looking down to make the ball appear “in your face.” Such corniness aside, Dante does demonstrate his affinity for working with miniatures. When, in a scene recalling a similar one from Poltergeist, a terrifying toy clown pursues Lucas in the basement, the puppet work successfully gives us a case of the willies. The majority of Dante’s scares resist barefaced confrontations with the audience, relying instead on our sense of dread and his young actors to communicate their fears.

Dane and Lucas make a believable pair of bickering siblings, the elder having grown too cool for his little brother, while the younger sibling looks up to Dane even as he antagonizes him. Their roughhousing recalls an era of growing up that may have passed, but for older viewers, especially those who grew up with a bullying older brother, these characters and their family dynamic will feel true. Dante has always been great with child actors, from The Explorers to Small Soldiers, and their relationship is the centerpiece of the film. The family’s frequent moving from place to place informs not only these characters, but what finally emerges from the hole. Hints throughout suggest physical abuse at the hands of their absent father, yet The Hole avoids graphic specifics to retain a sense of family entertainment value. Nevertheless, the psychological implications are always under the surface.

Dante’s touch (aside from including a mandatory cameo by Dick Miller) walks a fine line between going too far and exploring dull general audience fare, a line he’s been walking with considerable success his entire career. This early progenitor of the PG-13 rating knows exactly how to scare us through darkness and imagination, as opposed to buckets of blood. Of course, if Dante had a larger budget, perhaps this would be a different movie. Isn’t it nice how these things work out? Certainly, some of Theo van de Sande’s clunky cinematography would have been improved, much like the questionable CGI in the film’s nightmare finale, a mix of Tim Burton and Salvador Dali. But whatever quibbles we may find about the low-budget aspects of Dante’s production, his treatment of the characters—their sordid past, comic and frightening present, and uncertain future—and actors keep us laughing and squirming at all the right moments. For fans eagerly waiting for Dante’s return, The Hole offers plenty of chills and some interesting characters, and it should suffice in reminding us why the director remains a treasure for genre aficionados.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review