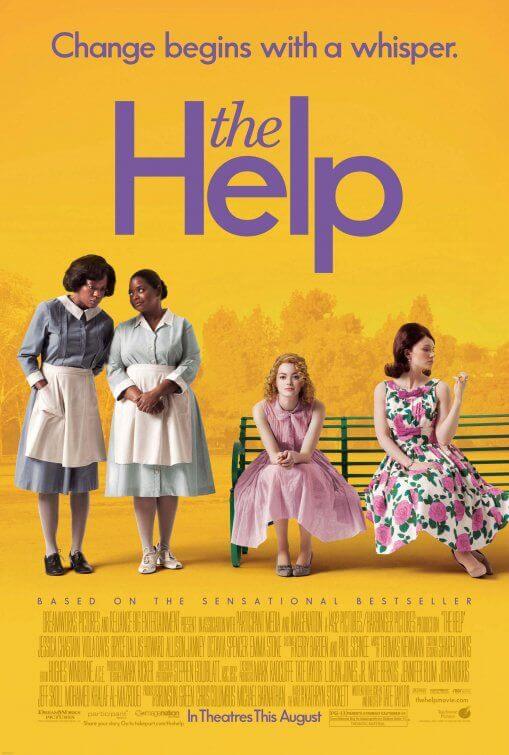

The Help

By Brian Eggert |

Hollywood glosses over the disturbing truth of race relations in Mississippi during the early 1960s in The Help, a dramatic comedy about Black maids and their haughty white employers. Set in an era where Jim Crow laws were alive and well, the adaptation of Kathryn Stockett’s debut novel was mismanaged by writer-director Tate Taylor and made into a syrupy tale somewhere between Steel Magnolias and Mississippi Burning. Any hope for a realistic portrait of this period is lost on a feel-good tone supplied by a white protagonist at the center, who allows the audience to keep a safe distance from horrors the Black characters must contend with every day in the Deep South. What’s worse is that, despite the filmmakers’ good intentions, the film actually manages to reinforce just as many stereotypes as it seeks to demonize.

Returning to her Jackson home from college, Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan (Emma Stone) secures herself a job writing for a local newspaper’s domestic column, but she has dreams of writing something noteworthy and important. She doesn’t know what that could be until she resumes bridge club with her former friends, now a tribe of housewives led by clanswoman Hilly (Bryce Dallas Howard), and listens to Hilly sermonize about putting forth an initiative to enforce outdoor Black-only toilets for their maids. Skeeter opts to write a book in secret from the perspective of these degraded servants, women who raise white children for self-important mothers while their own children are raised by someone else. Having thought her own childhood maid (Cicely Tyson) was more nurturing than her own mother (Allison Janney), she reaches out to local maids to tell their stories, putting all of them as well as herself in great danger.

But Skeeter’s story is merely a device through which we discover the heart of The Help. Viola Davis plays the stoic and poignant Aibileen, and her character’s sassy best friend, Minny, is played by Octavia Spencer. They’re the first to tell their stories to Skeeter, while others remain reluctant out of fear of being discovered. Aibileen works for a woman unfit to parent (Ahna O’Reilly) and keeps her head down even in the worst of moments. Minny’s last straw with her employer, Hilly, comes when a rainstorm prevents her from using her “special toilet” outside; but rain notwithstanding, Hilly refuses to let her use the house bathroom, so Minny uses it anyway and gets herself fired. Fortunately, she finds another position under a good-hearted social outcast (Jessica Chastain) and becomes a color-blind friend to her new employer. All the while, demoness Hilly tries to figure out why Skeeter dares talk to Black folk (although Hilly uses another word for them) in public.

Taylor’s structure baffles as he shifts perspectives while Aibileen narrates throughout. Multiple voices may work in a novel where a new chapter denotes a change in first-person subjectivity, but in a sentimental film like this one, consistency rules, and Davis’ voiceover doesn’t help bring the meandering stories together into one satisfying whole. Several subplots feel pointless, such as the one about Skeeter’s boyfriend, who disappears almost as fast as he’s established. Another subplot features Hilly’s replacement for Minny, who’s arrested for hocking a stolen ring; we never discover her fate. With either a defined episodic approach or one decidedly more focused, Taylor’s adaptation could have avoided its disorderly feel from start to finish. And had Taylor cut some of these excess subplots, the nearly two-and-a-half-hour film wouldn’t have felt so exceptionally long.

Fortunately, there’s an amazing cast at work here, beginning with Davis’ soulful performance, which is bound to earn her another Oscar nomination. Davis carries the weight of ages on her face and could have easily carried this story on her own. At times, Spencer, in her breakout role, doesn’t seem too forced and feels almost like comic relief next to Davis (in particular during the crude pie incident). Then again, Spencer’s role raises an eyebrow when her character prattles on about how much she just loves that fried chicken. Movies about race always have a way of unintentionally strengthening stereotypes they’re attempting to condemn and this film is no exception—especially when it comes to Hilly, who finally gets her comeuppance in the manufactured climax and (randomly) has the cold sore to prove it. Meanwhile, Chastain (from The Tree of Life) is delightful and almost unrecognizable as the ignorant but kind white-trash employer, and Sissy Spacek has a number of hilarious lines as Hilly’s observant, senile old mother. Despite being the protagonist, Skeeter is the least interesting character onscreen, regardless of Stone’s charm and growing star status.

Made with saccharine film stock, The Help refuses to truly face the issues it raises and instead opts to take a whitewashed, Hollywoodized look at a dark time in America’s history. Herein, Mississippi may be condemned as the most backward state in this country, but perhaps not with enough acidity (outside of silly plot contrivances like Hilly). This is a film that will expose you to horrible truths about a not-too-distant past and, in the end, makes you laugh and feel like there’s a happy ending, except there isn’t one. Not really. Even with Skeeter’s book, these maids still have to go back to their segregated lives, surviving under white employment and living in fear of stepping out of line. It’s an experience that manipulates you into feeling better about these characters’ lives, until, that is, the credits begin to roll and you realize the film hasn’t committed to their perspective. Instead, it takes The Blind Side approach and uses a cushion of white guilt to alleviate what should be grim and confronting.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review