The Harder They Fall

By Brian Eggert |

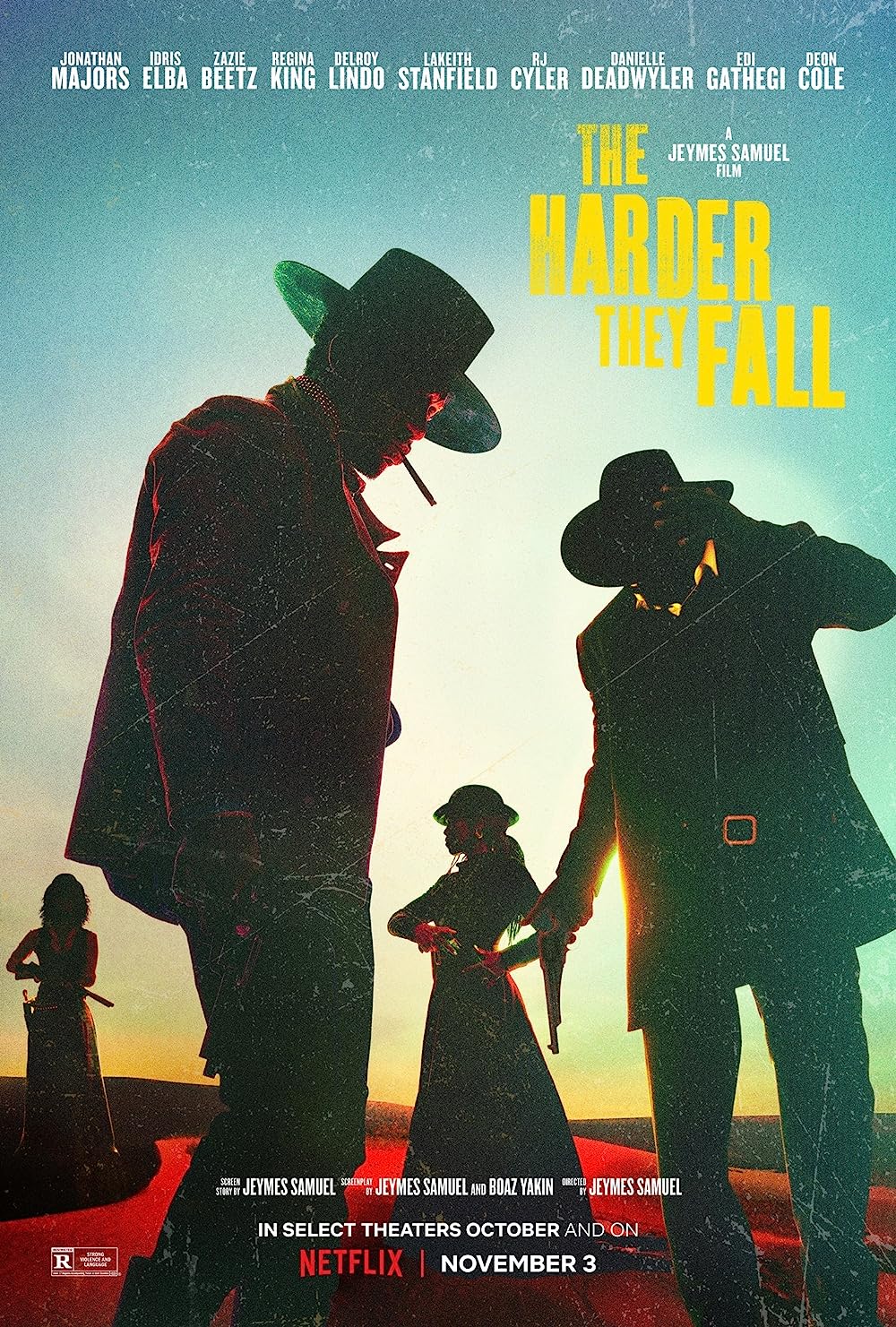

A lone rider stands on the tracks, waiting for the fast-approaching locomotive. Seeing what lies ahead, the conductor pulls the brake lever, sending squeals and sparks into the air until the train stops at the last moment. Under a long coat and hat, Regina King steps off her horse and stands defiantly. Infuriated, the conductor approaches her and shouts, “The hell are you doing? That ain’t no way to board a train, you damn, stupid n—.” But she stops his slur with a bullet. In one of many wildly entertaining sequences in The Harder They Fall, King appears as Trudy Smith, who has come to free her gang’s leader, Rufus Buck, from a prison transport. Set in a revisionist version of the Wild West, the film follows an incredible roster of Black performers playing real-life outlaws, gunslingers, thieves, and lawmen overlooked by history. But rather than commenting on race in the Old West, the film secures a place in the Western genre for people of color. Historically, Westerns only marginally acknowledge Black people. Yet, The Harder They Fall crafts an escapist, bloody, and stylish film about a rivalry between the Nat Love Gang and the Rufus Buck Gang, who shoot first and ask questions later.

A title before the credits informs us, “These. People. Existed.” Director Jeymes Samuel, who co-wrote the script with Boaz Yakin (Remember the Titans, 2000), shines a light on several figures whose names may be familiar only to Wild West history buffs. But The Harder They Fall isn’t about history; it’s about carving out a space for Black people in a genre that has often denied them. Those expecting any manner of biographical authenticity should look elsewhere (actually, if historical accuracy is your thing, cinema is probably the wrong place to seek it out). So while names like Nat Love, Stagecoach Mary, Cherokee Bill, and Bass Reeves all existed, they supply little more than a springboard—much in the same way filmmakers have used Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday in countless variations, few of them particularly true to life. Samuel doesn’t make this act of representation a didactic issue within the film, either. Instead, he presents a straightforward Western story filled with the usual trappings: saloons, train robberies, riders journeying across vast panoramas on horseback, bank heists, and vows of revenge.

The story opens with a young boy witnessing his father and mother slaughtered at the dinner table by Buck (Idris Elba), who carves a cross into the boy’s head for reasons that will become clear later in the film. Years pass and the boy grows up to become Nat Love, played in another charismatic performance by Jonathan Majors (HBO’s Lovecraft Country). Love has spent his life hunting down members of Buck’s gang with the help of his friends: sharpshooter Bill Pickett (Edi Gathegi), cocky quick-draw Jim Beckwourth (RJ Cyler), badass saloon owner and love interest Stagecoach Mary (Zazie Beetz), and Mary’s tough bouncer Cuffee (Danielle Deadwyler). Together, the Nat Love Gang has sustained itself by stealing from bank robbers. But with Buck captured and imprisoned for life, Love’s lifelong mission of vengeance is over—that is, until lawman Bass Reeves (Delroy Lindo) informs him that Buck has been pardoned for his crimes. And so, the six of them ride together to stop Buck’s gang, which includes Buck’s right-hand, Trudy, along with the psychopathic Cherokee Bill (Lakeith Stanfield), who’s known for shooting his opponents in the back.

Each performer has been perfectly cast and given generous monologues and scenery-chewing moments to bring their characters to life—none so much as King’s Trudy Smith, a ruthless piece of work fully embodied by the recent Oscar-winner. But then there’s Elba, whose size and gravitas suggest a Hannibal Lecter-level villain (called a “devil” by many characters). Just look at his prison transport cell: a metal box that might’ve belonged to Pandora herself, designed to store a super-criminal. However, after some initial terror—he bashes the gold teeth out of a sheriff’s mouth—Elba doesn’t play him as a one-note villain. By the showdown between Buck and Love, both men appear in tears, and the audience regrets that one of them must die. To be sure, this is a film filled with heartfelt speeches and deeply felt emotions, even while it manages to offer breathless shootouts and thrilling action. It embraces conventions and defies them, sometimes within the same character. For instance, Beetz’s Stagecoach Mary becomes a typical “damsel in distress” who, once released, unleashes fury for a bravado fight inside a dye shop festooned with multicolored cloths. At the film’s center is Majors, who appears strong and vulnerable, with a wounded quality that recalls John McClane’s human fallibility.

Known in the UK music industry as The Bullits, Samuel debuted his directorial chops with the 2013 short film, “They Die by Dawn,” a Western starring the late Michael K. Williams, Giancarlo Esposito, and Rosario Dawson. He’s a filmmaker with a clear understanding of the genre’s tone and style, evidenced by how he breaks convention with anachronisms. The soundtrack, for instance, features modern artists such as Jay-Z, Alice Smith, and CeeLo Green performing hip-hop and reggae songs (which, given the title, cannot help but bring to mind Jimmy Cliff’s 1972 Jamaican crime movie The Harder They Come). The CG-animated title sequence looks like something conjured for the James Bond or MCU franchises. In addition, Samuel injects a familiar, Tarantino-esque playfulness into the proceedings. When Nat Love and two of his compatriots enter a white town to rob a bank, the buildings, dirt in the streets, and even the soap look whitewashed. “It’s a white town,” parenthetical titles winkingly declare. Samuel even replicates Tarantino’s iconic trunk shot, or the Western equivalent thereof. And like Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (2009), Django Unchained (2012), and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), Samuel isn’t concerned with sticking to the facts. He employs familiar names and situations for something distinctly cinematic.

Still, Samuel marks his characters by the reality of the Black experience in America during this period. At one point, a character pulls down the handkerchief around his neck to reveal the scars from an attempted lynching. Hints of the commonplace horrors for Black people flesh out the film’s Wild West setting. In another scene, Cuffee, usually disguising herself in a man’s garb, puts on a dress to rob a bank. When she asks to make a withdrawal, the teller laughs derisively, explaining that she might have better luck in Redwood, a Black-owned town. But apart from a single moment where Nat Love looks into the camera and sings the lyric. “It’s in a distant view”—hinting at some modern-day parallels—the film resists becoming polemical about race and simply tells a Western story about Black characters. Just as John Wayne and Clint Eastwood had movies set in their predominantly white world, Samuel’s rogues’ gallery belongs to its own world. The Harder They Fall isn’t attempting to be an antithesis or a pointed statement; it aims to expand the boundaries of the Western to include significant roles for men and women of color, which the film industry has overlooked. Samuel acknowledges that another world existed in the Old West, and that world has gone underrepresented in mainstream cinema.

Capturing footage on location in Santa Fe, cinematographer Mihai Mălaimare Jr. (The Master, 2012) shoots real set pieces, horses, trains, and gushing fake blood. The viewer sees every dime of Samuel’s $90-million production. The Harder They Fall doesn’t skimp on the tangible details, whereas another production might be tempted to save time between takes by using CGI (cf. almost every Western in the last decade or more). Complete with lingering shots, bold colors, and beautiful scenery, it feels like a Leone-styled work of the 1960s blended with even more postmodern flourishes. Yet, the treatment never feels so misplaced that the story and characters become meta figures; Samuel integrates classical motifs and contemporary flourishes with emotional veracity that makes them come alive. And it’s doubtful that another Hollywood studio would fork over that sizable budget for an all-but-dead genre, starring a Black cast, from a screenplay not based on established intellectual property. So The Harder They Fall is the kind of entertainment that we should cherish for its scarceness; though, the world could use more of this kind of filmmaking. Fortunately, the film ends with a hint of more to come.

Although Woody Strode and Herb Jeffries often appeared in Westerns during the Golden Age of Hollywood, Black performers rarely took center stage. Sidney Poitier (with Buck and Preacher, 1972) and Mario Van Peebles (with Posse, 1993) attempted to correct that, but the Black Western remains a modest, underfunded subgenre. The Harder They Fall is a marvelous exception and hopefully an indicator of things to come—both from Samuel and the genre. Here’s a rare film that manages to be handsomely made, brutishly violent, intricately acted, and deliciously entertaining, all while doubling as a cinematic rarity. The cast is among the best in recent memory, and the director allows each performer multiple scenes to shine. At times, the film’s blend of idiosyncrasy and sincerity might seem unstable, like most Tarantino films. Still, Samuel’s careful balancing act of tones, genre love, and sheer entertainment value doesn’t get lost in the Brechtian self-awareness. Somehow, all of those touches combine into something uniquely exhilarating and singular. When it’s all over, The Harder They Fall doesn’t feel like a social prompt; it’s just a damn good Western.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review