The Happytime Murders

By Brian Eggert |

In The Happytime Murders, director Brian Henson, son the great Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets, takes a cue from his late father’s lesser-known work. Before launching The Muppet Show in 1976, the elder Henson created experimental shorts, some with puppets, some not, that bore adult themes and concerns. Much later, after several Muppet movies and other more mythical fare, including The Dark Crystal (1982) and Labyrinth (1986), the short-lived television show The Jim Henson Hour debuted an episode called “Dog City”—a pun-filled spoof of film noir and the gangster genre, populated entirely by canine puppets (in later episodes, they became cartoons). Layered with a combination of silliness and sly jokes meant for grown-ups, “Dog City’s” embrace of crime genre tropes demonstrated that Jim Henson was willing to experiment with his puppet workshop to provide more than children’s fare. After all, those early seasons of The Muppet Show were nothing if not loaded with humor bound to be missed by younger viewers.

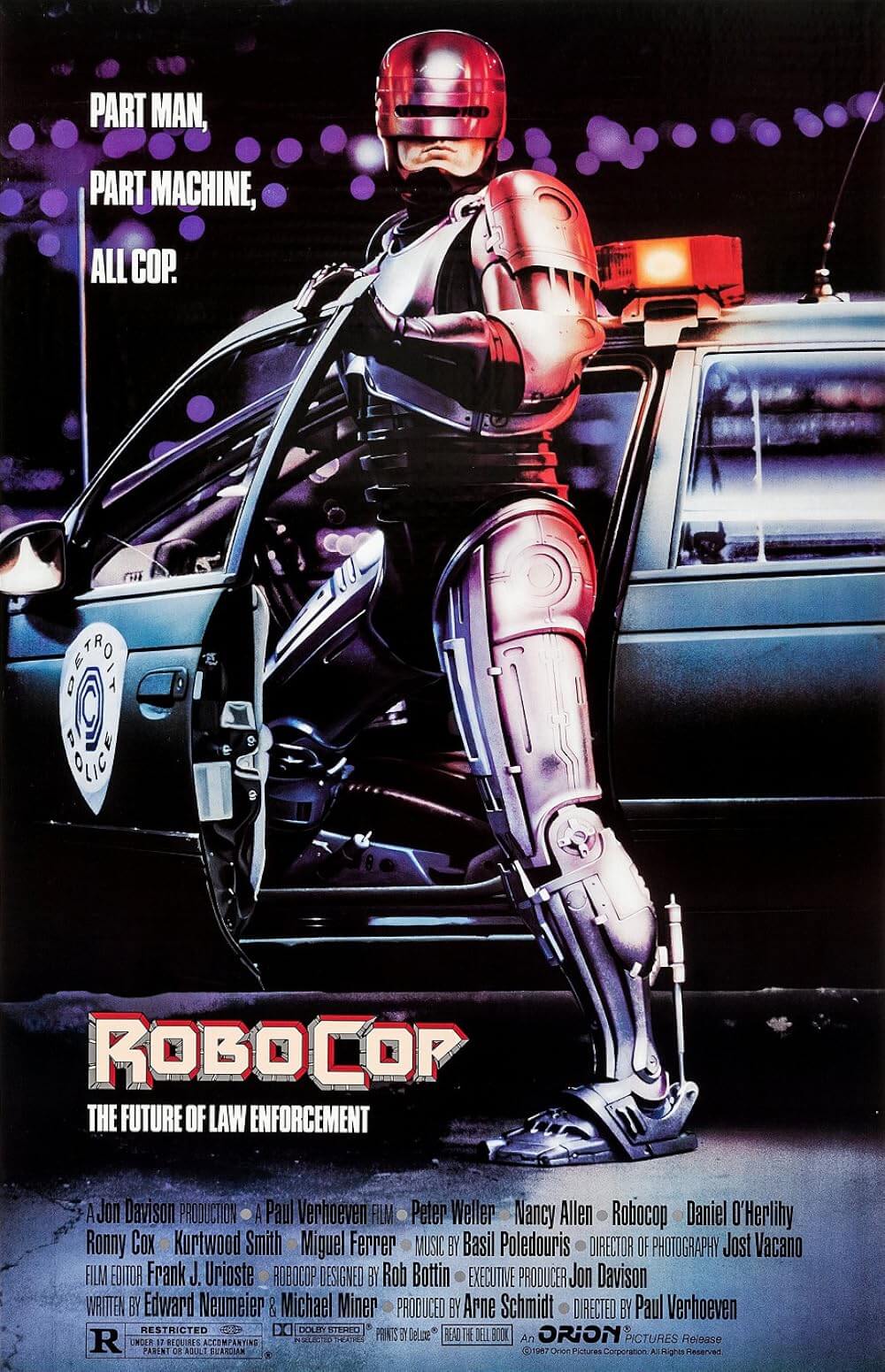

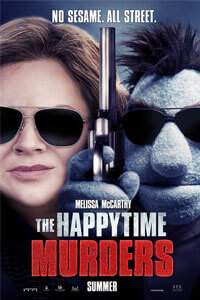

Even though Jim Henson had a streak of rebellious humor to his work, he certainly never conceived of anything remotely close to The Happytime Murders, which blends an L.A. cop drama with a gross-out comedy for an ungainly result. Adopting a hard-R rating and boasting a promotional campaign unabashedly proud of its sexual humor, the movie’s sole conceit is the apparent contrast of puppets, which are typically used in children’s entertainment, with X-rated material. Of course, this isn’t the first time a filmmaker has used puppets to produce something intentionally over-the-top bawdy. Peter Jackson’s wonderfully disgusting Meet the Feebles from 1989 celebrated its puppet characters in the sleaziest, most disgusting situations—such as the fate of Harry the hare, whose unidentified disease causes him to develop green, slimy boils, and projectile vomit.

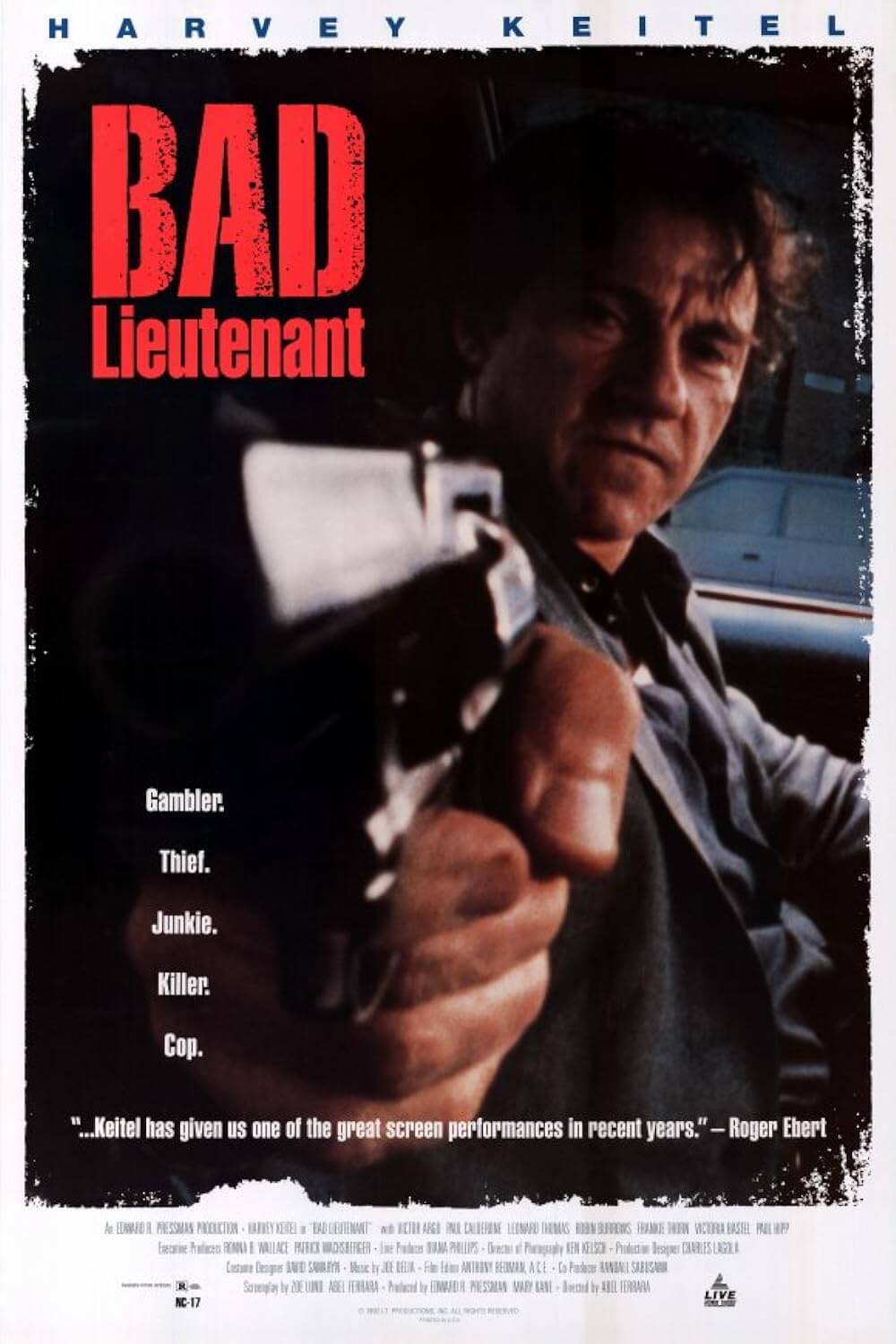

For the plot of The Happytime Murders, screenwriter Todd Berger draws inspiration from Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, a film that similarly blends family-friendly characters and a noirish murder mystery. Although that Robert Zemeckis film from 1988 remains a treasure and tonal breakthrough, The Happytime Murders fails to break any formal boundaries or create a previously unconceived genre mashup. Much like Roger Rabbit, the story seems to exist in the past (perhaps the 1990s), in a fictional world where humans coexist with a minority race of children’s entertainers—in this case, sugar-gobbling puppets. Also like Roger Rabbit, the yarn follows a washed-up private eye tasked with solving a string of murders. A hooded assailant is murdering the former cast members of a beloved 1980s children’s show, called “The Happytime Gang,” and only the ex-LAPD detective Phil Philips (Bill Barretta), the first-ever puppet cop, can catch them.

Along with being an LAPD cop yarn, a dirty-minded comedy, and a puppet show, The Happytime Murders is also a Melissa McCarthy star vehicle—a concept that comes with its own unfortunate baggage. McCarthy lends her abrasive, loud, and potty-mouthed persona to her character, Det. Edwards, who must team with her disgraced former partner, Philips, to catch the killer. Edwards and Philips have a history, as years ago a hostage-situation-gone-wrong ended with Edwards requiring a puppet liver and Philips getting kicked off the force. Now, Edwards’ puppet liver means she’s addicted to sugar, and Philips spends his nights drinking and remembering, though he could be on a date with his secretary, Bubbles (Maya Rudolph). Meanwhile, in a seeming unconnected case, a nymphomaniacal femme fatale, Sandra (Dorien Davies), hires Philips to expose her blackmailers and, in true noir tradition, the two cases end up being connected.

Similar to last year’s Netflix disaster Bright, the mix of genres provides a metaphor for racial intolerance, albeit a poor and meaningless one. The Happytime Murders is more interested in delivering lowbrow insults to taste and manners. McCarthy and the puppet cast uses “fuck” liberally, while depictions of puppet sex attempt to shock. One such sequence depicts a puppet octopus aggressively stroking the utters of an orgasmic puppet cow, resulting in a shower of milk. Another scene shows Philips ejaculating silly string onto the walls and ceiling of his office. It’s all rather juvenile and stupid, causing only the occasional chuckle. I liked how puppets have a deathly fear of dogs who might chew them up like a stuffed toy. I also liked the moment when Edwards and Philips enter the home of two “Happytime Gang” puppet actors who, despite being cousins, had two children together. The investigators hear screams and assume the worst, but instead, Edwards finds the couple’s mutated, inbred puppet children, one with three eyes and the other a cyclops, staring in the mirror, screaming at their own appearance. It’s this sort of pitch-black humor the screenplay needed more of.

The material’s limitations are reached within the first half-hour, by which point the audience can easily predict the killer’s identity, while the blue-collar comedy has already done its worst to shock and offend. By the time The Happytime Murders spoofs on the infamous leg-crossing scene in Basic Instinct (1992), the appearance of a puppet labia and purple pubic hair doesn’t really leave the viewer surprised, as the movie has left us numb to the continued displays of puppet sexuality. To counter the raunchiness, there’s also an unfunny stream of bad jokes throughout, including McCarthy’s grating and repeated use of the “An asshole says ‘what’?” to Joel McCale’s stuffy FBI agent character. When it’s all over, one cannot help but think The Muppet Show, or even “Dog City,” was smarter and edgier without the need to stoop so low.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review