The Grey

By Brian Eggert |

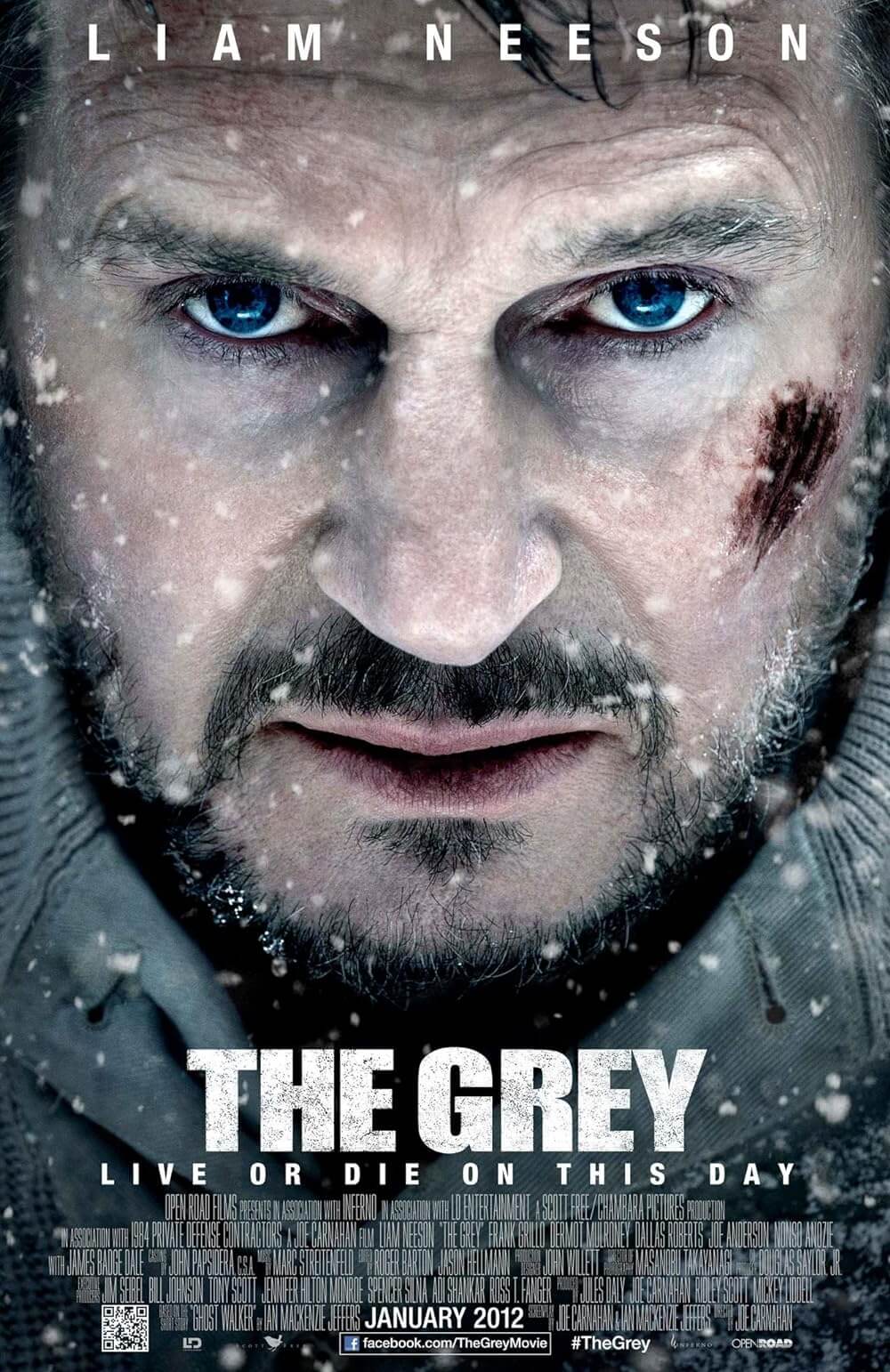

A plane carrying Alaskan oil drillers crashes in the wilderness. The few survivors huddle together and make fire, arguing about how to best conserve food and defy the cold. Snowy weather becomes the last of their worries, however, after their presence attracts a pack of timber wolves. Defending their invaded territory, the animals quickly taste human blood from the bodies scattered by the crash; now they’re ravenous man-eaters bent on stalking the remaining group of men across unforgiving terrain. The survivors are led by a knowing sharpshooter, Ottway, who was hired by the oil company to shoot down wild beasts that might attack the workers. Ottway is played by Liam Neeson, an actor whose presence alone adds substance to any character. As this life-or-death struggle in Jack Londonian territory moves forward, our expectation for a typical survival tale outcome is confronted by Ottway’s shrewd Nietzschean philosophy that Nature is a cruel, godless place that has no sympathy for humankind.

Indeed, midway into The Grey, one realizes that this isn’t a standard Man vs. Wild genre piece served up to reinforce the human race’s superiority over Nature. In fact, the extent to which director Joe Carnahan and his co-scripter Ian Mackenzie Jeffers oppose pandering to the needs of a mainstream audience is considerable, and impressive, and refreshing. Consider Ottway’s moody narration in the opening scenes. He reads from a letter that he’s written for a woman, presumably his wife, who in some way or another is lost to him. He remarks that he finds himself among a crew of “assholes,” ex-cons and vagabonds who wander through life without purpose. After his final searching words, he resolves to kill himself, but the sudden cry of a wolf convinces him not to. Soon Ottway and the survivors are running for their lives from the wolves, and many of them wish they had already died. It’s just one of several cruel twists of fate within this stark story.

Shot in 2011 during the winter months in the wilds of British Columbia, Carnahan’s film contains a brutalizing sense of authenticity in its scenes of harsh weather (this coming from a lifelong Minnesotan). But having worked in Alaska, the survivors’ heavy clothing has at least prepared them for the cold; despite the similar presence of wolves, there are no iced-skin peeling scenes like in Frozen. No matter how well-dressed, they’re not prepared for running through two feet of snow away from a wolf pack that watches their every move and picks off stragglers. Their provisions are reduced to airplane cocktails, and they have no cell reception, so hopes for rescue are nil. One man, the proud ex-con Diaz (Frank Grillo), finds a wristwatch with a GPS beacon, but since their ragtag group won’t be seen as a priority, none of them expect more than one or two rescue planes to be sent, which is not enough in the middle of nowhere. What’s more, with bloodthirsty beasts circling, they don’t have time to wait. Ottway believes their best chance of survival lies in the cover of nearby woods.

Their group quickly develops its own pack mentality, with Ottway as the clear Alpha Male, who bats down those who question his authority just as the wolves’ leader snarls away challengers. Carnahan spends considerable time developing the characters in extended sequences of dialogue around the campfire, some affable personal exchanges, and others heated arguments. Among the more interesting characters are Diaz; Talget, a faith-filled family man played by Dermot Mulroney; and Dallas Roberts as Hendrick, a humanist who willingly carries the wallets of the dead. Each role has multiple dimensions and lends the stripped-down survival scenario considerable weight, particularly when they wax philosophical on their respective religious views. Ottway believes in the here and now, but later finds himself screaming at the sky for help from above. Any other film of this sort might have given Ottway some slight inkling of hope, but then The Grey isn’t just any other film.

Neeson’s command of the screen is decisive, as it’s entirely possible the film wouldn’t have worked without him. There’s already talk of returning it to theaters in October 2012 to remind Oscar voters of his incredible performance. Bradley Cooper was originally cast as Ottway when the project was struggling to find a studio willing to finance such a disparaging film, and trying to imagine Cooper’s polished good looks in this situation now makes the idea laughable. When Neeson boarded the project, his involvement helped secure financing with Open Road, his post-Taken box-office draw enough to convince investors to place their money into a high-risk product. To be sure, despite action-heavy trailers, The Grey is not a crowd-pleasing adventure story but a grimly philosophized tale in which Neeson’s gravitas-laden presence enhances the already strong performances around him.

Much about its ending will grate on conventional audiences, but only because the marketing campaign has insisted on showing a particular scene in the trailer that suggests Neeson will engage in fisticuffs with a wolf. Along with the expectation that the film will reach its climax with this Man vs. Beast bout for the title of the Alaskan wilderness, there are several “mainstream Hollywood” elements that the film resists. An antithesis for The Grey would be another survival movie, The Edge (1997), where Anthony Hopkins and Alec Baldwin are hunted by a bear, and yet, at all the right moments, they fight back and win, or stumble upon a cabin stocked with guns and ammunition, or flag down a helicopter for rescue. Among the best aspects of this film are the clichés that are not present, leaving us with only Ottway’s belief that life or death is merely a frame of mind, and that God won’t be intervening no matter how much he shouts at the sky.

Ever since his gritty cop thriller Narc from 2002, the promise of Carnahan’s talent has been squandered on lowbrow material, from the excessive actioner Smokin’ Aces to the fun escapism of The A-Team. But all his potential fulfills its past promises now, ten years later, as The Grey is an unforgivingly brutal, brilliantly acted, beautifully shot motion picture. Cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi imbues the film with striking visuals that range from gritty blizzard grain to picturesque landscapes. At one point, a character cannot go on and determines to live out his last moments looking at one of Takayanagi’s infinite backdrops, and we can’t blame him. Not only is the scenery gorgeous, but the opposition is terrifying, enhanced by a layering of eerie wolf howls created by the top-notch sound team. Above all else is Neeson’s performance, and Carnahan’s willingness to carry his film’s conviction to an ending that punctuates the entire film with a sudden, uncompromising cut.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review