Reader's Choice

The Green Mile

By Brian Eggert |

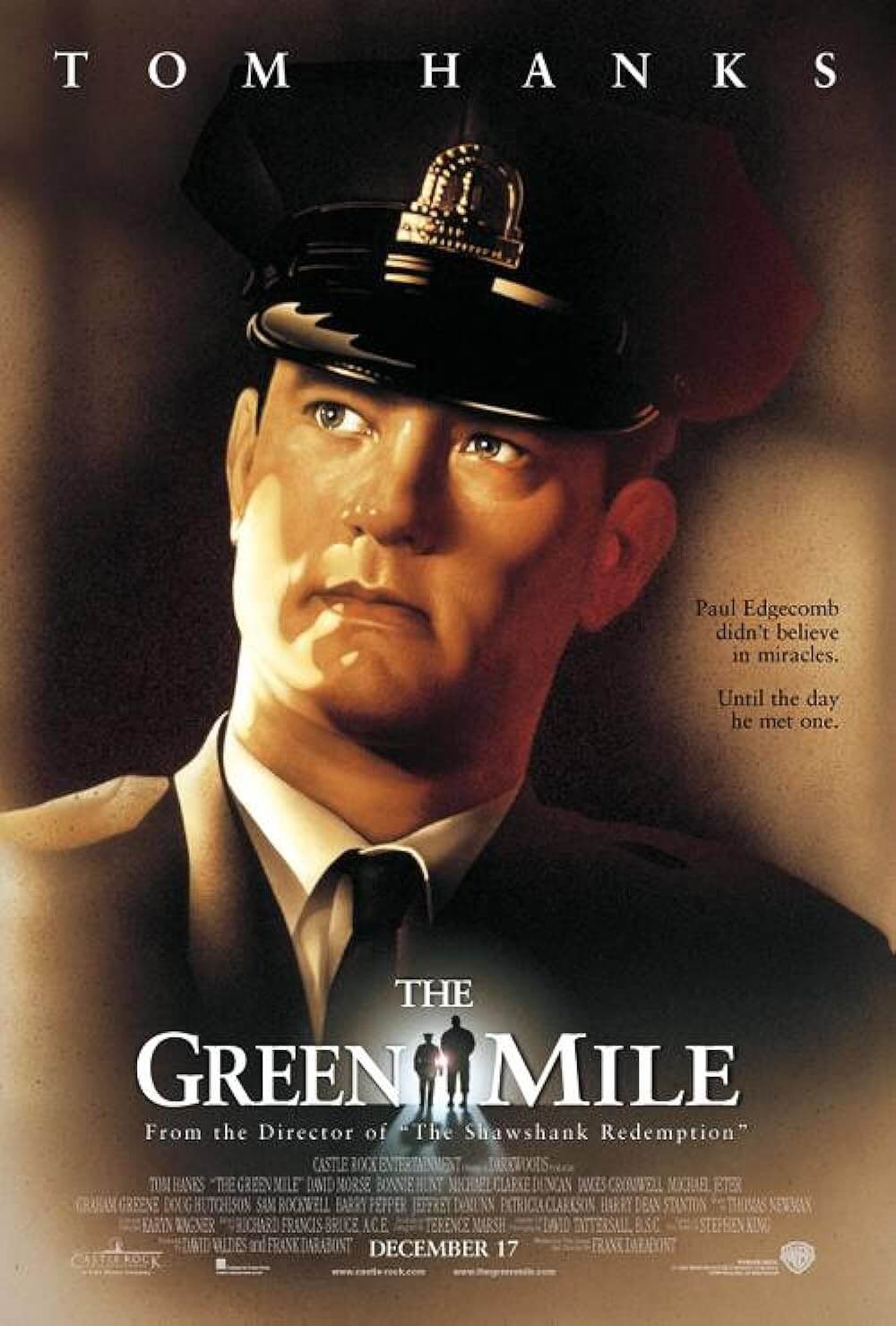

The Green Mile finds writer-director Frank Darabont operating in two modes, that of a sentimentalist and an unyielding cynic. Darabont has given us stirring examples of each mode. In the former, he explored hopeful stories such as The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and The Majestic (2001), whereas his latter mode isolated and confronted his audience with The Mist (2007), an unforgettably grim horror picture. But his 1999 film, one of Darabont’s many adaptations of a Stephen King text, finds an uncommon balance between his occasional Capra-esque optimism and his capacity for bitter despair. Many have censured The Green Mile for its more earnest scenes and the limited characterization of its sole black character, and while I wrestle to defend the film against such critiques, I must acknowledge that the power of its drama is immersive and moves me. More compelling, however, is Darabont’s willingness to present the story as another feel-good prison film, but instead, he delivers a saddening tale of spiritual uncertainty. Far less uplifting than his other maudlin efforts, The Green Mile is a film of extreme poles, comfortably pleasant in one moment and appallingly cruel the next. Though it might have been reduced to a mushy, touching crowd-pleaser, Darabont’s willingness to explore the darker regions of King’s story distinguish it.

Not long after The Green Mile was published in 1996, Darabont approached King about acquiring the rights. Two years earlier, Darabont had released The Shawshank Redemption at Warner Bros. with underwhelming box-office performance; regardless, it received seven Oscar nominations and became a major success on home video and in cable television markets. Repeated at-home viewings raised the film to a cult status and, over time, it was celebrated as a favorite among viewers—it soon earned the number one spot on IMDB’s user-voted list of the top 250 films, which it maintains to this day. Given the belated renown of The Shawshank Redemption, Darabont received a wider berth with The Green Mile, including a budget of $60 million, a dream cast, and a luxurious three-hour runtime, all for a film that proves quite bleak. Even so, the result performed well during the December holiday season, earned accolades for relative newcomer Michael Clarke Duncan, and secured four Oscar nominations, including Best Picture. In some critical circles, reviewers took Darabont to task for the saccharine, feel-goodness of his work. Writing in Film Comment, Dave Kehr criticized the film’s geniality and described the inmates as having “the fuzzy huggableness of hand puppets.” Just as many critics assessed The Shawshank Redemption as an oddly pleasant film for a story about life in prison, a few writers, standing out in the majority of positive assessments, would reduce The Green Mile to feel-good entertainment.

The critical notion of The Green Mile’s syrupy condition has always confused me. Even though it contains moments of sentimentality, it is a bleak tale. Here’s a story with devastating jolts of emotion (including three electric chair executions, each of them horrific to varying degrees), animal cruelty, prison violence, and an ending that leaves its protagonist in a perpetual state of foreboding and existential crisis. It’s a three-hour commercial film whose tension remains unresolved to rather gloomy and inauspicious effect. The story is told by the elderly Paul Edgecomb (Dabbs Greer), who lives inside a senior living center. The overhead music—the Mantovani orchestra’s performance of “Charmaine,” the same music played in the mental institution in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)—draws a sinister comparison, underscoring the questions that have tormented and imprisoned him. He tells a fellow inmate (Elaine Connelly) about his time in the 1930s as a guard at the Louisiana State Penitentiary’s death row, the E-block nicknamed “the green mile” for its olive floors. Though moments of humor do occur, and the sedate “intensive care ward” mannerism on the green mile seems calmer and gentler than your average prison film, the narrative that unfolds has never left me feeling happy or sedated as a viewer.

The guards are mostly decent men, including the towering Brutus “Brutal” Howell (David Morse), the family man Dean (Barry Pepper), and the older Harry Terwilliger (Jeffrey DeMunn). They’re headed by Edgecomb (Tom Hanks), who leads an idyllic, empty nest life with his supportive spouse, Jan (Bonnie Hunt). But among the guards is Percy Wetmore (Doug Hutchison), a petulant sadist whose aunt is married to the governor, and who plans to stick around in this thankless job until he can “see one cook up close.” Behind bars and waiting for a turn in the electric chair, dubbed “Old Sparky,” the prisoners consist of a quiet Native American (Graham Greene), a cracked trustee (Harry Dean Stanton), and the regretful Cajun Eduard Delacroix (Michael Jeter, outstanding)—who eventually befriends a pet mouse, teaches it a few modest circus tricks, and names it Mr. Jingles. Their latest arrival on the green mile is John Coffey (“like the drink, only not spelled the same”), a towering but outwardly gentle figure embodied by Michael Clarke Duncan. Though Coffey was convicted of killing two little girls, Edgecomb finds his behavior unlike that of other death row inmates; the prisoner shakes hands, maintains a fear of the dark, and often cries at night. And as Edgecomb eventually learns after an hour into the film, Coffey has a supernatural ability to “take back” disease and even death—a process that entails a glowing inhalation of negativity, followed by an exhalation of swarming, gnat-like darkness.

The guards are mostly decent men, including the towering Brutus “Brutal” Howell (David Morse), the family man Dean (Barry Pepper), and the older Harry Terwilliger (Jeffrey DeMunn). They’re headed by Edgecomb (Tom Hanks), who leads an idyllic, empty nest life with his supportive spouse, Jan (Bonnie Hunt). But among the guards is Percy Wetmore (Doug Hutchison), a petulant sadist whose aunt is married to the governor, and who plans to stick around in this thankless job until he can “see one cook up close.” Behind bars and waiting for a turn in the electric chair, dubbed “Old Sparky,” the prisoners consist of a quiet Native American (Graham Greene), a cracked trustee (Harry Dean Stanton), and the regretful Cajun Eduard Delacroix (Michael Jeter, outstanding)—who eventually befriends a pet mouse, teaches it a few modest circus tricks, and names it Mr. Jingles. Their latest arrival on the green mile is John Coffey (“like the drink, only not spelled the same”), a towering but outwardly gentle figure embodied by Michael Clarke Duncan. Though Coffey was convicted of killing two little girls, Edgecomb finds his behavior unlike that of other death row inmates; the prisoner shakes hands, maintains a fear of the dark, and often cries at night. And as Edgecomb eventually learns after an hour into the film, Coffey has a supernatural ability to “take back” disease and even death—a process that entails a glowing inhalation of negativity, followed by an exhalation of swarming, gnat-like darkness.

Among the most unsettling aspects of The Green Mile is Percy, a vile and contemptuous character, among the most hateful in any film. He’s a weaselly character who delights in torturing inmates and exercising whatever cruel powers his authority lends him. Despite their crimes, the monk-like Edgecomb hopes to create a calm and accommodating mood to give the inmates a sense of tranquility before sending them into oblivion. Percy wants to watch them squirm, take away whatever they hold dear—in Delacroix’s case, Mr. Jingles—and finally, give the death order. And whenever he seems to show a faint sign of humanity, he answers it with a dose of barbarism. Percy is also a coward who endangers his colleagues when he fails to act in a crucial moment after the new inmate, William “Wild Bill” Wharton (Sam Rockwell, unhinged), feigns catatonia to get the jump on the guards. Percy’s only match in the despicable department, Wild Bill urinates and spits chewed Moon Pies on the guards, spews debased remarks, and slings racist epithets, earning his place in the block’s padded cell. He takes particular delight in confronting Percy—a rare and perverse treat in a scene when Wild Bill finds Percy at his weakest and most sniveling. In a bit of Kingian convenience, Wild Bill is also the killer of the two girls that landed John Coffey on death row. But both are detestable characters, some of the vilest ever conceived in King’s massive inventory of awful human beings, though brilliantly played by both Hutchinson and Rockwell.

Darabont’s screenplay follows the episodic structure of King’s novel, which was published in six parts between March and August of 1996. The ebbs and flows of the story settle the viewer into the routines of the green mile, the even-tempered disposition of the guards and periodic rehearsals of the next execution—a calm frequently interrupted by Percy’s behavior or Wild Bill’s outbursts. Each death row inmate has his own subplot, and the way they intermingle allows them to build into a greater whole. But the overarching story centers on Edgecomb’s handling of Coffey, who is hardly present for the first 90 minutes of The Green Mile, whereas the latter half entails Edgecomb reconciling that the prisoner’s abilities constitute a bona fide miracle from God. It’s something everyone on duty comes to believe; even Warden Hal Moores (James Cromwell), whose wife Mildred (Patricia Clarkson) suffers from a brain tumor until Coffey consumes it. Coffey is surely a Christ-like character, capable of healing the sick and reviving the dead, and his death echoes the self-sacrifice of the crucifixion. In another way, Coffey resembles countless King characters endowed with telepathy, precognition, and other supernatural talents (in Carrie, The Shining, Firestarter, The Dead Zone, et al.)—symbols of Otherness compared to the grounded characters that usually guide King’s narratives.

If I have a hesitance toward The Green Mile today, it stems from two factors. The first belongs to Darabont’s occasional cornball sensibilities, which present a greater contrast to the grim material of this film than his even-toned approach on The Shawshank Redemption, and therefore stand out more. Death, execution, wrongful imprisonment, and blotting out one of God’s miracles each present stark ideas, but Darabont contrasts those ideas with a rather pleasant death row experience. King told author Tony Magistrale, “I like to joke with Frank that his movie was really the first R-rated Hallmark Hall of Fame production.” While that comparison may be too narrow, there remains a certain easygoing atmosphere to the film, one that proves effortless for the viewer to settle into and absorb. It is both a problem given the subject matter and a strength given how the three-hour-plus runtime breezes by. More distracting is how Darabont handles John Coffey’s “take it back” scenes. In each of the four times that Coffey uses his abilities (on Edgecomb’s infected urinary tract, to resurrect Mr. Jingles, to take away Melinda’s tumor, and to punish Percy), Darabont uses similar camera movements. The close-ups that show Coffey’s hand or mouth glowing as he uses his power, followed by his heaving of the dark material into the air, are accompanied by Thomas Newman’s twinkling score and a God’s-eye-view camera angle that floats upward as Coffey expels the sickness or death. For a film that spends much of its time grounded in medium shots on the death row corridor, these flourishes feel unduly fanciful.

If I have a hesitance toward The Green Mile today, it stems from two factors. The first belongs to Darabont’s occasional cornball sensibilities, which present a greater contrast to the grim material of this film than his even-toned approach on The Shawshank Redemption, and therefore stand out more. Death, execution, wrongful imprisonment, and blotting out one of God’s miracles each present stark ideas, but Darabont contrasts those ideas with a rather pleasant death row experience. King told author Tony Magistrale, “I like to joke with Frank that his movie was really the first R-rated Hallmark Hall of Fame production.” While that comparison may be too narrow, there remains a certain easygoing atmosphere to the film, one that proves effortless for the viewer to settle into and absorb. It is both a problem given the subject matter and a strength given how the three-hour-plus runtime breezes by. More distracting is how Darabont handles John Coffey’s “take it back” scenes. In each of the four times that Coffey uses his abilities (on Edgecomb’s infected urinary tract, to resurrect Mr. Jingles, to take away Melinda’s tumor, and to punish Percy), Darabont uses similar camera movements. The close-ups that show Coffey’s hand or mouth glowing as he uses his power, followed by his heaving of the dark material into the air, are accompanied by Thomas Newman’s twinkling score and a God’s-eye-view camera angle that floats upward as Coffey expels the sickness or death. For a film that spends much of its time grounded in medium shots on the death row corridor, these flourishes feel unduly fanciful.

The second factor pertains to the prevalent discussion around the film as a site of the so-called “magical Negro,” where a saintly black man or woman (usually a man) helps their white counterpart to deal with a central conflict of the film. Usually, the “magical Negro” has a spiritual quality, using his folksy wisdom and moral superiority as a member of the repressed to assist or offer crucial advice that helps the white character. The conflicts in these situations emerge from the white character’s perspective, whereas the person of color remains supplementary in his Otherness. It is most commonly a matter of some spiritual consequence, as opposed to a tactile dilemma to overcome, allowing the “magical Negro” to offer their angelic guidance to relieve the white character’s crisis of the soul. Along with characters in films such as Cuba Gooding Jr. in What Dreams May Come (1998) and Will Smith in The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000), Coffey unquestionably fits this racial stereotype. As the only significant black character in the film, Coffey is described as “monstrous big” but an “imbecile” who is nonetheless good-hearted and, of course, endowed with supernatural abilities. Those abilities, combined with his reassurance of Edgecomb in the finale, resolve most of the tensions in the film, which is told from Edgecomb’s point of view. However, though Coffey may absolve Edgecomb of any wrongdoing by allowing the wrongful execution to take place, he does not completely remove Edgecomb’s spiritual conflict.

If there’s any consolation in watching The Green Mile as a text of racial representation, it’s that the imprint of Coffey has lasted long after Edgecomb’s hundredth birthday. Edgecomb asks Coffey, “On the day of my judgment, when I stand before God, and He asks me why did I kill one of his true miracles, what am I gonna say? That it was my job?” Coffey offers some comforting words at the time, but he has also “infected” Edgecomb with a long life. In the bookend scenes when Edgecomb tells his story, he reveals his curse: he has lived to 108 and will continue to outlive his loved ones, doomed to a life of reflection about his choice to execute Coffey and wonder if it was the right decision. Will God forgive him? There is no clear answer. The Green Mile leaves a lasting stain on the protagonist; he continues unsettled and guilt-ridden, stuck on his personal death row. “Sometimes the Green Mile seems so long,” he says in the final line, underlining that Edgecomb cannot wait for his death. It’s a grim conclusion for a film often considered to be overly sentimental and pandering to the audience, which is a reaction I have never understood. This is a film that leaves its protagonist in limbo, questioning, and certainly doubtful, that he will make it into Heaven. Evidently, Coffey’s ability to resolve the hero’s conflict did not work, and Edgecomb has been left in a state of existential dread. What is so pandering about an old man fated to live out his many years in a state of mental anguish?

But The Green Mile also buries the historical reality that Coffey was probably railroaded into a conviction because of his race. A single scene in which Edgecomb visits Coffey’s defense attorney (Gary Sinise) to determine the convict’s guilt reveals that he didn’t receive the best defense. Sinise’s character draws a comparison between a black man and a “mongrel dog,” suggesting that both should be handled with swift violence when they misbehave, revealing the pervasive racism of the South. Although technically part of the text, the discussion of Coffey’s race as it relates to his predicament has been reduced to this single scene, whereas the extratext has more to offer. After all, the period and setting were hostile for people of color. In the reality of the Jim Crow South, Coffey may have been lynched as opposed to imprisoned. Still, the film acknowledges, in a roundabout way, that due to the place and time, any attempt at freeing or fighting for Coffey would be impossible for Edgecomb. Racism is ingrained into the culture, and Edgecomb is helpless to fight it. But the fact that the racism of the South becomes part of the milieu, if an underemphasized part, is both troublesome for its limited representation and something the viewer cannot deny exists within the film. In some small measure, The Green Mile confronts the racist South, suggesting that its consequence has left a permanent brand on Edgecomb that shows no immediate sign of fading.

But The Green Mile also buries the historical reality that Coffey was probably railroaded into a conviction because of his race. A single scene in which Edgecomb visits Coffey’s defense attorney (Gary Sinise) to determine the convict’s guilt reveals that he didn’t receive the best defense. Sinise’s character draws a comparison between a black man and a “mongrel dog,” suggesting that both should be handled with swift violence when they misbehave, revealing the pervasive racism of the South. Although technically part of the text, the discussion of Coffey’s race as it relates to his predicament has been reduced to this single scene, whereas the extratext has more to offer. After all, the period and setting were hostile for people of color. In the reality of the Jim Crow South, Coffey may have been lynched as opposed to imprisoned. Still, the film acknowledges, in a roundabout way, that due to the place and time, any attempt at freeing or fighting for Coffey would be impossible for Edgecomb. Racism is ingrained into the culture, and Edgecomb is helpless to fight it. But the fact that the racism of the South becomes part of the milieu, if an underemphasized part, is both troublesome for its limited representation and something the viewer cannot deny exists within the film. In some small measure, The Green Mile confronts the racist South, suggesting that its consequence has left a permanent brand on Edgecomb that shows no immediate sign of fading.

But as Roger Ebert observed about the film’s racial dynamics and the relationship between Edgecomb and Coffey, “the story has so well prepared us that the key scenes play like drama, not metaphor, and that is not an easy thing to achieve.” Indeed, hyper-aware of the widespread commentary about race as it relates to The Green Mile upon this viewing, I was surprised to discover that during the film I was so engaged in Darabont’s storytelling that its potential ramifications only surfaced afterward. At times, the late Michael Clarke Duncan’s performance transcends the “magical Negro” trope, creating a soulful and tortured character whose mind, acting like a receiver to the cruelty in the world (“like pieces of glass in my head, all the time”), has grown tired of existence. Putting him out of his misery as Edgecomb does is not an easy choice—one with which he never reconciles; it follows him for nearly a century, and beyond. Moreover, the ever-affable Hanks and the other actors playing guards (Morse, Pepper, and DeMunn each soar) seem to have genuine bonds, whereas the range of acting styles among the inmates never ceases to impress. Another actor taken too soon is Jeter, whose moments of elation with the mouse have a charmed tenderness, making his end all the more horrific.

If Darabont somehow made The Shawshank Redemption easy viewing—the contention made by its detractors—the highs and lows of The Green Mile leave the viewer in a puddle of tears, worrying for Edgecomb, who may live forever, regretting his refusal to act on behalf of a black man in the Jim Crow South. This is hardly a film that dismisses race, though it doesn’t treat race as the leading text either. Using a range of dramatic tools, Darabont blends the more disturbing qualities of the story with his prevailing humanism and sentimentality—a temperament often chided by critics. “There’s nothing wrong with honest sentiment,” Darabont told The Guardian in an interview in which the filmmaker admits to being emotionally manipulative of his audience. “The point is, do you appreciate the manipulation or resent it? Do you notice it, or do you completely, blindly give yourself over to it?” At times, you notice The Green Mile tugging your heartstrings. But aside from a moment or two over the course of three hours, the viewer gives in, entrenched in the proceedings and deeply affected by the spell of these characters. Still, like Edgecomb, we are visited upon by its implications and occasionally embarrassed by its resounding effect.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your support, Avshalom!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review