The Greatest Showman

By Brian Eggert |

The Greatest Showman, a musical shot in the ritzy, post-modern style of Baz Luhrmann, portrays the life of circus impresario P.T. Barnum. Hugh Jackman, the congenial star of stage and screen, appears as Barnum, lending his Broadway voice to the role. The flashy numbers reach for something akin to Andrew Lloyd Webber by way of modern pop-music, but all the razzle-dazzle of this expensive production, and considerable charms of its cast, cannot distract from the film’s emptiness and forced attempts at social awareness. Setting aside any hope for historical or biographical accuracy, the film portrays Barnum as a champion of marginalized groups and outcasts. And that’s true enough, in a sense that Barnum gathered a troupe of “freaks” (the bearded lady, Tom Thumb, the poodle woman, the dog boy, etc.) and put them on display to sell as many tickets as possible. His circus made its fortune from The Other and, rather than grant his performers a sense of empowerment, he exploited them for his own gain. Quite incongruously, The Greatest Showman suggests that Barnum is a heroic figure, a woke entertainer and family man, who also capitalized on animal suffering and the veritable prostitution of human oddity. Since the film plays by the unbound rules of a musical, we shouldn’t be taking history so literally; nevertheless, the distracting irregularities here cannot be ignored.

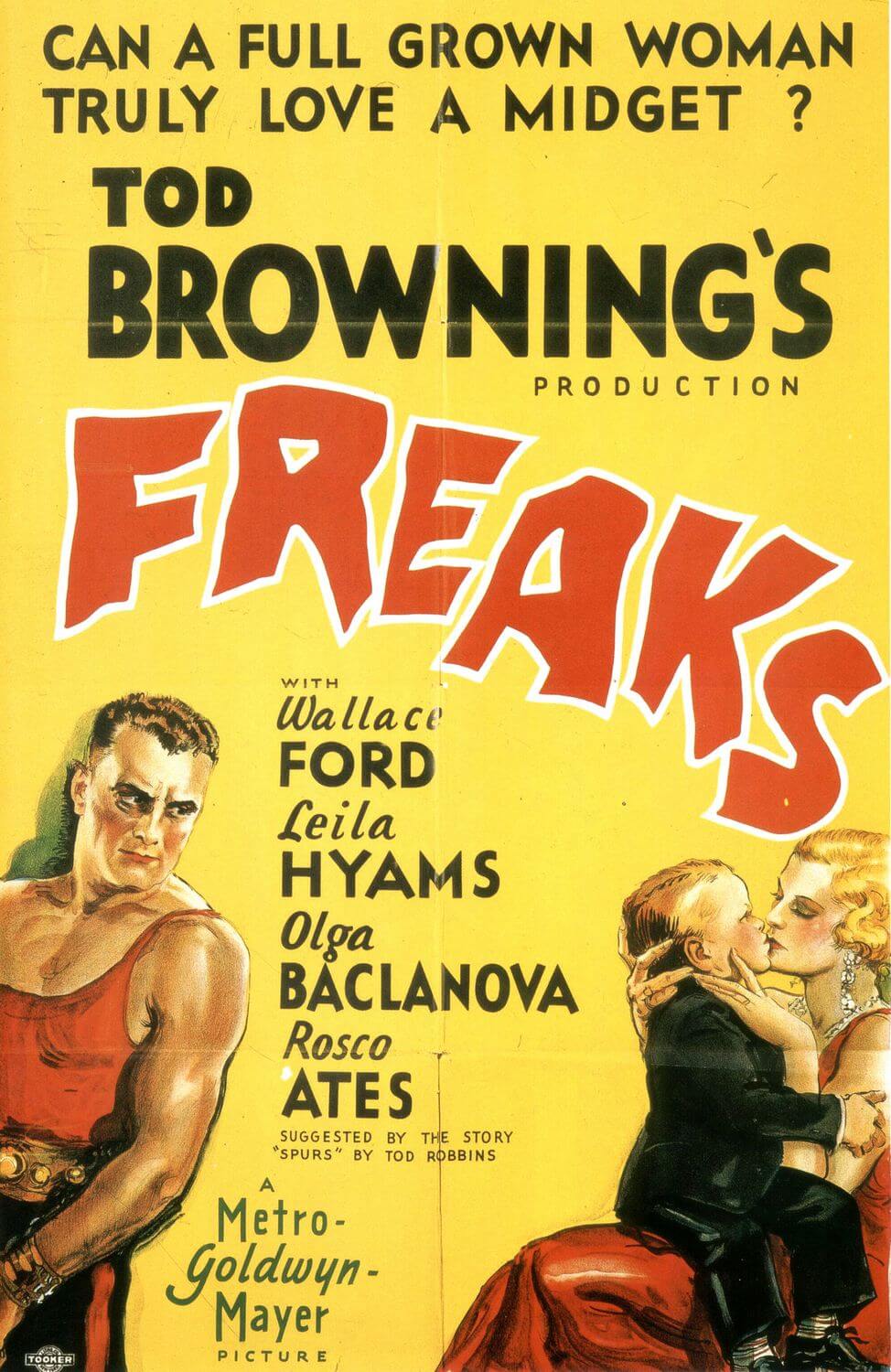

The real-life Barnum was a huckster, drawing the masses with entertainment from “freak shows” to his own ringmaster windbaggery (he was nicknamed the “Prince of Humbug”): His circus boasted a “Feegee Mermaid,” a sideshow attraction in which a monkey’s upper half was sewn to the tail of a fish. People with physical defects, almost exclusively non-white, were put on display as “human curiosities”—among them the Guyanese-born Prince Randian, “the human torso” who also appeared in Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932). Barnum helped make stars out of the “Siamese Twins,” Chang and Eng Bunker. He sold tickets to the autopsy of his star Joice Heth, an African-American performer his show claimed was 161 years old. And when his main attraction, a six-ton African elephant named Jumbo, died after more than twenty years in captivity, Barnum separated the remains into pieces, sent those pieces to several touring shows, and sold tickets to Jumbo’s various body parts. Later in life, though he held steadfast to an anti-slavery rhetoric, his shows continued to feature blackface minstrelsy and promote abhorrent racial stereotypes. Call it a historical irony that the screenplay by Jenny Bicks and Bill Condon treat Barnum like a social justice warrior.

Nineteenth-century New York circuses were unpleasant places by today’s standards, filled with vile smells, cruel people, and mistreatment abound, but the filmmakers rethink history and present them in an acceptable light. The film opens with a young Barnum growing up on the streets of New York. After reaching adulthood, he marries Charity (Michelle Williams), a childhood sweetheart from a well-to-background. They have two young girls and live a modest life. Before long, the restless Barnum dreams up a “museum” of oddities, both human and otherwise. He recruits a group of “peculiar” people for his museum and sells tickets in hopes of providing “a good laugh” to spectators. Aside from a few anti-freak protests and a subplot about racism (directed toward a trapeze artist, played by Zendaya, who seems poised for real stardom), Barnum resolves that bad press is good publicity, and he continues making a fortune. At the same time, Barnum resents that the upper crust hasn’t accepted him as artistically viable. Despite having their wealth, he doesn’t have their class. To remedy this, he hands over the sideshow to his junior partner (Zac Efron) and begins promoting Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind (Rebecca Ferguson), much to the dismay of his family and freakshow performers. Of course, he inevitably learns that his true calling belongs not on a posh concert tour, but under the tent.

Many of The Greatest Showman‘s songs include inspirational, positive lyrics about following your dreams and accepting who you are, but the film never quite gives its sideshow characters agency. None of these characters have more than a single dimension, and some of them are even treated poorly by the production. Take Sam Humphrey, an actor with skeletal dysplasia, which has made him shorter than most. Humphrey plays Charles Stratton, a famous dwarf performer that was dressed to look like Napoleon and paraded about on a horse. Humphrey seems to have been hired solely because he fits the height requirements, whereas the filmmakers remain uninterested in whether his physical defect is the same as Stratton’s (dwarfism and skeletal dysplasia: not the same). Worse, the filmmakers seem preoccupied with Humphrey having the right look, but deny him a full performance by grossly dubbing over his voice with a deeper-toned actor in both dialogue and singing scenes, making Humphrey’s performance a shell. (If nothing else, The Greatest Showman has captured the spirit of Barnum by exploiting physical disorders for their appearance.)

Many of The Greatest Showman‘s songs include inspirational, positive lyrics about following your dreams and accepting who you are, but the film never quite gives its sideshow characters agency. None of these characters have more than a single dimension, and some of them are even treated poorly by the production. Take Sam Humphrey, an actor with skeletal dysplasia, which has made him shorter than most. Humphrey plays Charles Stratton, a famous dwarf performer that was dressed to look like Napoleon and paraded about on a horse. Humphrey seems to have been hired solely because he fits the height requirements, whereas the filmmakers remain uninterested in whether his physical defect is the same as Stratton’s (dwarfism and skeletal dysplasia: not the same). Worse, the filmmakers seem preoccupied with Humphrey having the right look, but deny him a full performance by grossly dubbing over his voice with a deeper-toned actor in both dialogue and singing scenes, making Humphrey’s performance a shell. (If nothing else, The Greatest Showman has captured the spirit of Barnum by exploiting physical disorders for their appearance.)

First-time director Michael Gracey, whose experience in commercials and special FX leaves him ill-suited for the complicated task of shooting a musical, apparently shot every scene from every angle, and then left the footage to his staggeringly large team of six editors (!). The result is a mishmash of cutting in each musical number, leaving the viewer in confusion from the lack of visual coherence. Elaborate set designs, costumes, and CGI-enhanced backdrops give the picture the requisite visual spectacle. But Gracey seems to have borrowed the same manner of confusing excess as his fellow Aussie, Luhrmann. Accordingly, everything onscreen looks gorgeous, including production designer Nathan Crowley’s stagy sets and costumer Ellen Mirojnick’s theatrical costumes. Still, the material might work better on the stage, even if many of the songs have a sameness in both style and message. Among the standouts is “Come Alive,” a number that presents a clever mimicry of Michael Jackson’s mid-1980s sound.

Although this review talks a lot about actual history versus the film’s representations, it should be stated that films are not required to represent an accurate history. Every time you read “based on a true story” before a film, you should raise an eyebrow and approach with suspicion, and remind yourself that films are not histories. Some historical inaccuracies are easy to overlook when they’re limited to having a few facts or timelines wrong for dramatic effect. This is the nature of cinematic storytelling. But historical retellings that include hero worship, especially when the given hero remains suspect, presents a troublesome deviation that, in the case of The Greatest Showman, cannot be ignored. After all, Barnum was a professional hype artist not above the occasional exaggeration (or outright lie), racial prejudices, a willingness to exploit for his own profit, and a barker’s subtlety (today he might have run for president). Calling him a humanitarian for putting people of various races, creeds, colors, and shapes on stage is hardly heroic if it’s for all the wrong reasons (some of which this film repeats). Many will enjoy The Greatest Showman for its surface sheen; however, even a cursory glance into the real story makes the film feel like a deception that attempts to give marginalized people a voice but instead continues to exploit them.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review