The Great Gatsby

By Brian Eggert |

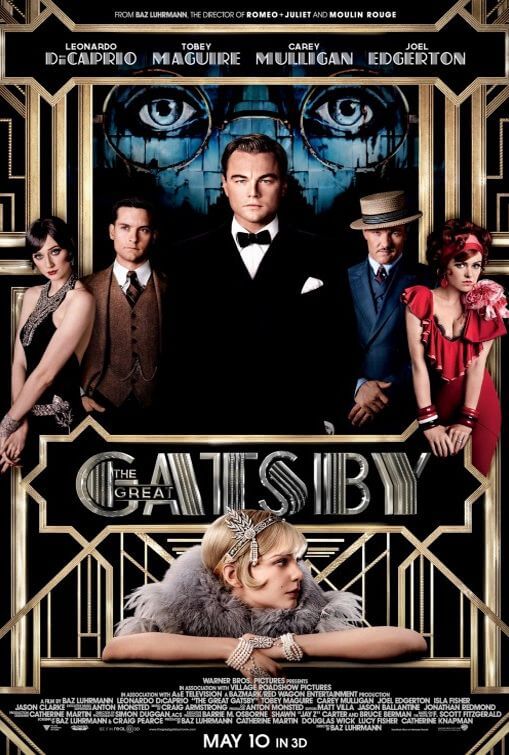

An over-stylized and under-thought adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s seminal novel, Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby features a number of excellent performances from a gorgeous cast, all undone by Luhrmann’s characteristically bloated production. Another of the Moulin Rouge director’s post-modern attempts to infuse the old with the new, the film contains none of the nuances of Fitzgerald’s novel; every chance for subtlety is replaced by Luhrmann’s need for high-energy ornamentation. This version may not be as categorically dull as the 1974 version starring Robert Redford, but incorporating 3-D effects, modern music from the likes of Kanye West and Lana Del Rey, choppier cutting than a Michael Bay movie, and endlessly repeated visual metaphors wasn’t what Fitzgerald’s tale needed to make it relatable for modern viewers.

Full of glitz and glam, the film opens with narrator Nick Carraway (Tobey Maguire) inexplicably recounting his experiences with Jay Gatsby from a sanitarium, a storytelling device that not only unnecessarily frames the narrative but diverts from the book (there’s no mention of a sanitarium in Fitzgerald’s text). His doctor (Jack Thompson) advises him to write down his woes, and throughout the remainder of the picture, there’s cause for Luhrmann to project Nick’s scribblings and typewriter letters onto the screen in an overused visual motif. But then Luhrmann films The Great Gatsby with many such overused motifs. As Nick sets the stage of New York in the twenties, he describes the coal-ridden town just outside of the city and describes a forgotten billboard advertising a forgotten optometrist, the image of a spectacled figure provides symbolism for how God sees all. And from thereon out, anytime someone mentions God in the film, Luhrmann cuts to the billboard in a most repetitive stroke.

For those forgetting their obligatory high school reading, the story follows Nick meeting his cousin Daisy (Carey Mulligan) in New York circa 1922. A failed writer who’s moved to the city to sell bonds, Nick rents a small house next to a Xanadu owned by the fabled, mysterious Gatsby. After dining with Daisy, her unfaithful husband Tom (Joel Edgerton), and Daisy’s best friend, Jordan (newcomer Elizabeth Debicki, quite good), he hears stories about the unexplained origins of Gatsby’s wealth and past. Soon Nick receives an invitation to one of Gatsby’s elaborate parties, and the man reveals himself to Nick. Played by Leonardo DiCaprio, Gatsby’s entrance in this scene is splendid and appropriately charismatic, and DiCaprio’s performance only grows more complicated as the story progresses and the mystique about Gatsby slowly fades into that of an idealistic impostor who wants only to rekindle his love with Daisy. Both Nick and Gatsby learn that romanticism has no place in a world of riches and materialism.

The film’s finest touches belong to the cast, headlined by the melancholy Maguire in a role similar to those he had in The Ice Storm, The Cider House Rules, and Wonder Boys. Even in his thirties, he still can manage that innocence-lost persona that has suited him so well before. DiCaprio embodies Gatsby’s most suave moments and his most fragile, perfectly balancing the character’s artifice with his blind optimism. Mulligan and Edgerton are both excellent, the former a seemingly endearing type and the latter exactly what he appears to be. Jason Clarke (from Zero Dark Thirty) appears as Gatsby’s killer George B. Wilson, and Isla Fisher is juicy as Wilson’s doomed wife, Myrtle. Overall, it’s an attractive cast that’s ultimately overshadowed by Lurhmann’s invasive decorations and jumpy style, which do a criminal disservice not only to the actors but to Fitzgerald’s intended purposes for the book.

With Romeo + Juliet (1996), Luhrmann’s over-amped style modernized Shakespeare’s play into an accessible tale, and the gamble worked because, as history has proved, the Bard is universal. Fitzgerald’s essential critique of American opulence is enhanced by the backdrop of the Roaring Twenties’ excess in New York City—the jazzy parties, ever-flowing alcohol, and other documented freedoms. Luhrmann’s production brings the era to life through bright colors and CGI backgrounds and seems to relish this aspect of the story more than any other. But his application of modern style into a period-specific setting is uneven throughout the film, detrimentally so. In the earliest scenes, the editing allows no more than a microsecond between cuts, barely allowing us to absorb the details of shimmering confetti and Art Deco designs. The integration of modern music into the soundtrack is also annoyingly inconsistent: sometimes he uses Craig Armstrong’s traditional score; sometimes old-timey tunes like “Let’s Misbehave”; and then out of nowhere comes “100$ Bill” by Jay-Z.

In the end, it’s evident that Lurhmann refuses to commit to the cynical worldview of Fitzgerald’s book by changing a key detail in Gatsby’s death. Lurhmann allows Gatsby a moment of hope before he dies at the thought of Daisy calling him, and therein misses the cold despair presented in the novel. This isn’t much of a surprise, since Lurhmann knows little of restraint or subtlety. More than his exaggerated vibes or inconsistent mood, the ending is perhaps the director’s greatest misstep in his screenplay co-written by Craig Pearce. However noble it is to attempt an adaptation of The Great Gatsby for the modern age, Lurhmann’s over-the-top and certainly overwrought approach may be refreshingly unconventional to some, but it fails to achieve Nick’s crucial observer status as “within and without” by delighting far too much in the billowing decadence of the setting. Lurhmann seems more interested in repeating his Moulin Rouge success in another fusion of pop music and history than truly embracing the themes of Fitzgerald’s novel.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review