Reader's Choice

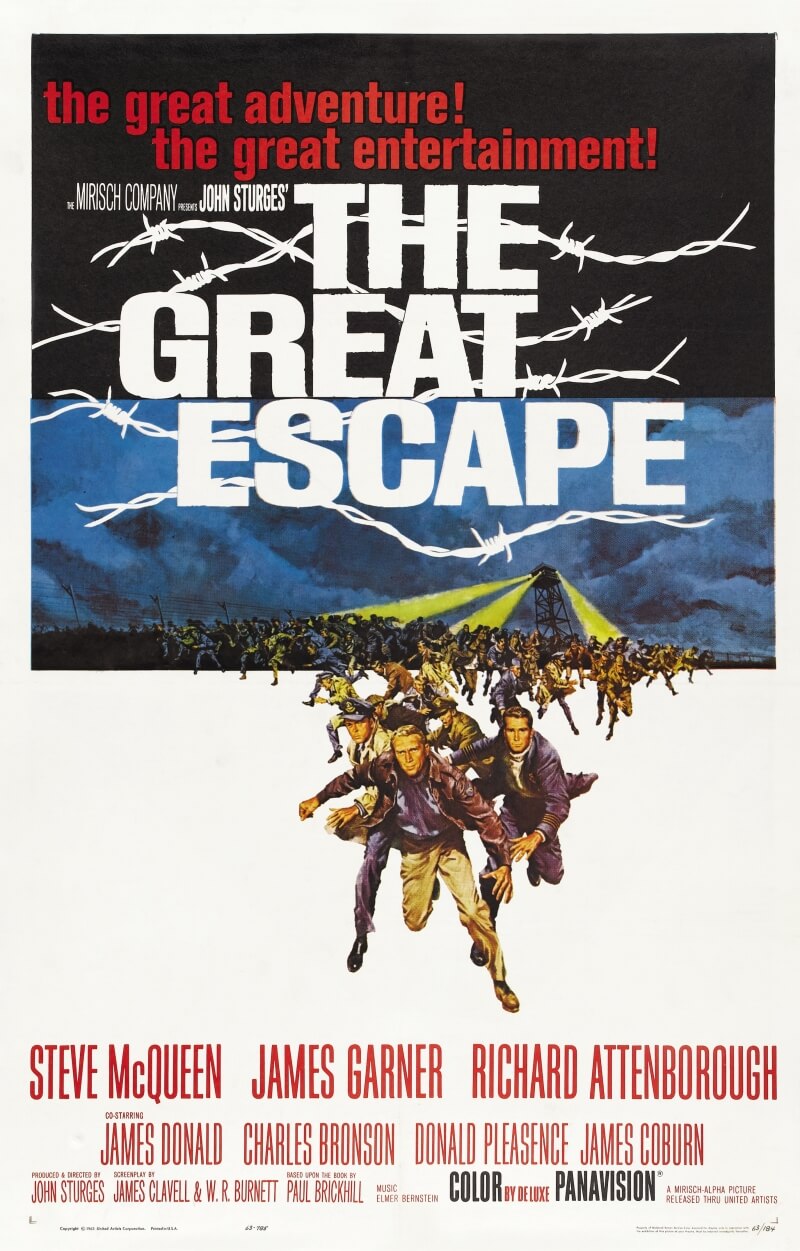

The Great Escape

By Brian Eggert |

Reading both vintage and modern reviews of The Great Escape, one finds countless examples of writers who describe the 1963 hit as “great escapism” or a timeless adventure. The film is seen as a stirring World War II entertainment. There’s even a tradition in the United Kingdom of watching it on Christmas, though it makes no reference to the holiday. How strange, since director John Sturges delivers a nearly three-hour film in which mainly British prisoners of war in a German camp plan to carry out the biggest escape in history, and they mostly fail. Although their plan aims to free 250 prisoners, a miscalculation means only 76 make it out. Of those, 50 are recaptured and then executed by their Nazi wardens, 23 more are returned to the camp, while only three men make their way to freedom. “What the hell kind of escape is this?” complained Samuel Goldwyn, who turned down the option to produce. “Nobody gets away!” Calling The Great Escape mere escapism, then, hardly seems accurate. And yet, the film endures given its themes of defiance, resourcefulness, determination, and teamwork in the face of detainment, the death of fellow soldiers, and the mission’s ultimate failure. It’s unlikely material for a rousing war film, but it continues to entertain, even if that notion raises the alarm.

After all, The Great Escape never mentions Nazi crimes, avoids thinking about the Holocaust, and circumvents any discussion of the ideologies at play. The film is laser-focused on the true story of a mass escape from Stalag Luft III, a camp built in 1942 by the German Luftwaffe (air force) in Poland for Allied airmen from other POW camps who had a record of frequent escapes. The camp was designed to keep even the most creative soldiers inside, complete with rocky soil that would make tunneling difficult, barbed-wire fences, and watchtowers with mounted guns. But the film isn’t about the opposition, their crimes against humanity, nor even the extreme measures to keep escapees detained (for instance, the film leaves out the seismographs used by the Germans to detect digging). Rather, following Paul Brickhill’s nonfictional and first-hand account, first published in 1950, the story details the group effort among Allied soldiers that led to the escape attempt in March 1944.

After discovering Brickhill’s book, Sturges sought to develop the story into a motion picture. He had admired French director Jean Renoir’s prison break drama, Grand Illusion (1937), and certain similarities, such as the prisoners disposing of tunnel dirt through their pant legs in the yard, appealed to him (Frank Darabont would repeat the technique in 1994’s The Shawshank Redemption). However, there were distinct differences between the portrait of German soldiers in Renoir’s World War I film and the Nazis in The Great Escape. For one, there’s no soldier’s code or mutual respect, no acceptance of the “duty” to escape in the latter film. In contrast, Renoir found a basic humanism on both sides of the conflict, even if class divisions remained intact. Sturges’ film would get at the inhumanity of the Nazis in a roundabout way—by simply ignoring their humanity altogether and concentrating entirely on the Allied soldiers. But the proposed production would have cost must more than studios at the time were willing to spend. It took Sturges over a decade of rejections and the box-office performance of The Magnificent Seven (1960), a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), to convince Hollywood that he could manage a large-scale production and turn a profit.

After discovering Brickhill’s book, Sturges sought to develop the story into a motion picture. He had admired French director Jean Renoir’s prison break drama, Grand Illusion (1937), and certain similarities, such as the prisoners disposing of tunnel dirt through their pant legs in the yard, appealed to him (Frank Darabont would repeat the technique in 1994’s The Shawshank Redemption). However, there were distinct differences between the portrait of German soldiers in Renoir’s World War I film and the Nazis in The Great Escape. For one, there’s no soldier’s code or mutual respect, no acceptance of the “duty” to escape in the latter film. In contrast, Renoir found a basic humanism on both sides of the conflict, even if class divisions remained intact. Sturges’ film would get at the inhumanity of the Nazis in a roundabout way—by simply ignoring their humanity altogether and concentrating entirely on the Allied soldiers. But the proposed production would have cost must more than studios at the time were willing to spend. It took Sturges over a decade of rejections and the box-office performance of The Magnificent Seven (1960), a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (1954), to convince Hollywood that he could manage a large-scale production and turn a profit.

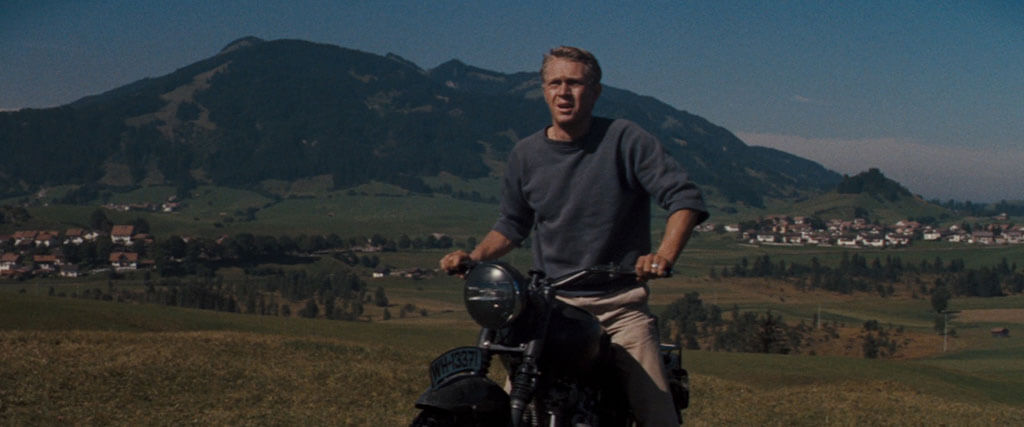

After The Magnificent Seven exceeded expectations, the Mirisch Company finally agreed to produce Sturges’ dream project. United Artists would distribute the film, based on a script credited to authors W. R. Burnett and James Clavell (though uncredited writers also contributed). Sturges relied on a technical advisor involved in the actual escape from Stalag Luft III for authenticity, recreating details such as using bedframe boards to support the tunnel’s passages. Still, the opening titles claiming “every detail of the escape is the way it really happened” have since been debunked. Elsewhere, The Great Escape marked a kind of reunion for Sturges and several cast members from his hugely successful The Magnificent Seven. Steve McQueen, James Coburn, and Charles Bronson all starred in the Western, which shares plenty of similarities with The Great Escape. Both feature an iconic score by Elmer Bernstein and boast an ensemble of almost exclusively male characters, most described with a single character trait or flaw, who team up to fight an oppressive force—murderous bandits in the earlier film, Nazis in the latter film. Like The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape performed better than anticipated. Although the production cost nearly $4 million to complete, it earned upwards of $11 million and became one of 1963’s top box office performers after spectacles like Cleopatra and How the West was Won.

The film opens with trucks delivering a group of British and American soldiers into the Stalag Luft III, where the newly appointed camp Commandant, Colonel Von Luger (Hannes Messemer), tells the Group Captain Ramsey (James Donald), “There will be no escapes from this camp.” The Nazis have assembled a who’s who of POW escape artists. “We have, in effect, put all our eggs in one basket,” says the Commandant. “And we intend to watch this basket carefully.” Nevertheless, the POWs refuse to submit and quietly wait out the war. Bartlett (Richard Attenborough), the head of the prisoners and codenamed Big X, considers it his duty to “harass, confound, and confuse the enemy to the best of my ability.” He announces a scheme to embarrass the Nazis by carrying out the most elaborate escape plan in history. Although the impatient Captain Hilts (McQueen) has his own, more immediate plans, Big X arranges for hundreds of forged documents, civilian clothing, distractions galore, and not one but three separate tunnels—named “Tom,” “Dick,” and “Harry.” Regardless of the extensive planning, when the time comes, their efforts are discovered. The daring race to a neutral border is breathless and futile since only three men evade their Nazi pursuers. Even so, those captured and murdered by the Nazis are remembered, and the POWs resolve to continue their escape attempts.

Although Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17 (1953) and others like it had covered the topic before, The Great Escape popularized the prison movie trope of an ensemble defined by emblematic handles. James Garner’s resourceful American who can acquire any number of forbidden goods goes by “The Scrounger.” Donald Pleasance is “The Forger,” despite his increasing blindness. Bronson’s claustrophobic digger is called “Tunnel King.” Gordon Jackson is simply known as “Intelligence.” The list goes on. These titles help establish that each individual has a precise and functional role in the group effort, leading to the film’s later status as a nationalistic symbol of unity and celebration of fallen British heroes. If the film has a weakness, it’s how the script declaws the villainous threat with its two central Nazis among the many other faceless guards: The Commandant seems reluctant to offer a “Heil Hitler” salute to Gestapo men and appeals to Hilts by saying, “We are both grounded for the duration of the war”—an attempt to relate to Hilts on a human level by ostensibly saying, “We’re both at an undesirable station.” And Garner all but befriends Robert Graf’s naive Werner, a German soldier quick to chum-up with the charismatic American “in a scene that deserves to be called a seduction,” observed film critic Shiela O’Malley. The few Gestapo and SS characters, while appropriately despicable, barely register. But in reality, their execution of 50 prisoners led to a war crime trial and 18 convictions.

Although Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17 (1953) and others like it had covered the topic before, The Great Escape popularized the prison movie trope of an ensemble defined by emblematic handles. James Garner’s resourceful American who can acquire any number of forbidden goods goes by “The Scrounger.” Donald Pleasance is “The Forger,” despite his increasing blindness. Bronson’s claustrophobic digger is called “Tunnel King.” Gordon Jackson is simply known as “Intelligence.” The list goes on. These titles help establish that each individual has a precise and functional role in the group effort, leading to the film’s later status as a nationalistic symbol of unity and celebration of fallen British heroes. If the film has a weakness, it’s how the script declaws the villainous threat with its two central Nazis among the many other faceless guards: The Commandant seems reluctant to offer a “Heil Hitler” salute to Gestapo men and appeals to Hilts by saying, “We are both grounded for the duration of the war”—an attempt to relate to Hilts on a human level by ostensibly saying, “We’re both at an undesirable station.” And Garner all but befriends Robert Graf’s naive Werner, a German soldier quick to chum-up with the charismatic American “in a scene that deserves to be called a seduction,” observed film critic Shiela O’Malley. The few Gestapo and SS characters, while appropriately despicable, barely register. But in reality, their execution of 50 prisoners led to a war crime trial and 18 convictions.

Not everyone enjoyed The Great Escape upon its release. Some cited the film’s lengthy runtime or adventurous tone as a problem; others cheered the same characteristics. Writing in The New York Times, Bosley Crowther remarked, “Nobody is going to con me—at least not the director, John Sturges—into believing that the spirit of defiance in any prisoner-of-war camp anywhere was as arrogant, romantic and Rover Boyish as it is made to appear in this film.” Crowther and a few other critics cited the film’s almost blithely disobedient tone, likening it to fantasy more than a gritty war picture. Other writers got into the spirit of things, though similar to Crowther, overlooked the grim finale. The Hollywood Reporter called it “a great adventure picture, tense with excitement, rich in character, leavened with humor, novel in setting and premise.” Similarly, in her New York Herald Tribune review, Judith Crist described it as “a first-rate adventure film, fascinating in its plot, stirring in its climax, and excellent in performance.” The Los Angeles Times wrote, “There have, sure, been literally hundreds of prison-break movies, civilian as well as military. ‘The Great Escape’ digs, hammers and claws its way, if not to the top of the list, then awfully close to it.”

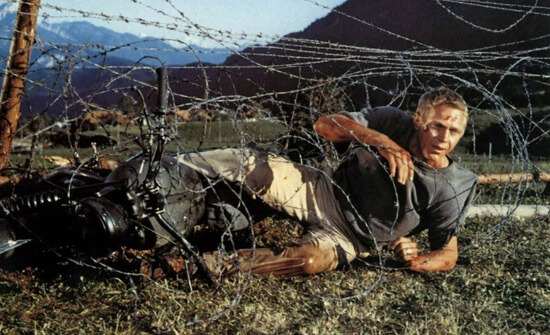

The Great Escape also transformed McQueen from the charismatic star of The Blob (1958) and The Magnificent Seven—not to mention his three seasons on CBS’s Wanted: Dead or Alive—into a box-office draw and Hollywood fixture throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Initially, McQueen was nervous about taking the part of an American alongside a group of skilled British actors; however, he quickly learned how to steal every scene. Demanding that Sturges add the motorcycle sequences to show off his skills on a bike, too, helped turn his otherwise peripheral character into the film’s secret weapon. Most critics at the time called attention to McQueen’s central performance, whether he was tossing a baseball into his glove or landing a daring jump over a barbed-wire fence on a motorcycle. The writers in Life magazine and Variety likened McQueen’s screen presence to James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and John Garfield—full of the cockiness and shine that lend themselves to movie stars. The Great Escape transformed McQueen into a household name; he followed the role with several major blockbusters throughout the next decade: The Cincinnati Kid (1965), The Sand Pebbles (1966), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), and his biggest hit, The Towering Inferno (1974). The epitome of the Rover Boy mentality critiqued by Crowther, McQueen’s charming and optimistic presence onscreen almost does Sturges’ downer finale an injustice. But this film is hardly exceptional for its good-humored tale of bravery in the face of Nazis.

Hollywood cinema of the 1950s and 1960s turned World War II into the stuff of mass entertainment. For every film that considered the “madness” of war in the manner of The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), there were many more titles like The Guns of the Navarone (1960) or countless John Wayne pictures that turned the conflict into toothless action. The trend would culminate in 1965 when CBS debuted Hogan’s Heroes. For the next six years, American viewers watched the jolly relationship between Allied POWs and their Nazi captors play out in a comic farce. The Great Escape isn’t so easy to navigate when demarcating the line between entertainment and reality. Sure, there was never a daring motorcycle chase or doomed airplane escape like those depicted in the film—there wasn’t even an American like Hilts; he was added to please American audiences. Most of the details were drawn from Brickhill’s book, including the choir practice to distract from the sound of hammering or the dreadful undershot of the tunnel from the treeline. Still, there was plenty more Hollywood artifice to transform the story into a curiously rousing good time. When the end titles (“This picture is dedicated to the fifty”) appear onscreen, it feels almost like an afterthought.

Hollywood cinema of the 1950s and 1960s turned World War II into the stuff of mass entertainment. For every film that considered the “madness” of war in the manner of The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), there were many more titles like The Guns of the Navarone (1960) or countless John Wayne pictures that turned the conflict into toothless action. The trend would culminate in 1965 when CBS debuted Hogan’s Heroes. For the next six years, American viewers watched the jolly relationship between Allied POWs and their Nazi captors play out in a comic farce. The Great Escape isn’t so easy to navigate when demarcating the line between entertainment and reality. Sure, there was never a daring motorcycle chase or doomed airplane escape like those depicted in the film—there wasn’t even an American like Hilts; he was added to please American audiences. Most of the details were drawn from Brickhill’s book, including the choir practice to distract from the sound of hammering or the dreadful undershot of the tunnel from the treeline. Still, there was plenty more Hollywood artifice to transform the story into a curiously rousing good time. When the end titles (“This picture is dedicated to the fifty”) appear onscreen, it feels almost like an afterthought.

If this assessment of the film has seemed to come down on The Great Escape, then allow me to clarify: This is among the most engrossing war pictures or prison break pictures to come out of Hollywood. It blends a terrific ensemble cast and memorable characters in scenes that remain fixed in the mind’s eye: McQueen’s confident walk back to the hotel set to Berstein’s playful score; Bronson’s breakdown in the tunnel at the last minute; Jackson succumbing to the same trick he warned others about; Pleasance faking sight until Big X exposes him; the lighthearted moonshine interlude; the breathless moment when a Nazi guard discovers the tunnel; and the devastating crash of McQueen’s motorcycle, followed by his desperate reach toward Switzerland. Regardless of whether one deems the material too light given its subject matter, Sturges creates a spirit of optimism and defiance in the face of the enemy. POWs could not allow themselves to dwell on their families or the sociopolitical implications of the war, nor does Sturges dwell on such weighty ideas. Instead, he replicates the same mindset his characters must uphold to remain committed to the task at hand. That the film mirrors its characters’ way of thinking is a stroke of genius, really, and one used to similar effect to portray the mental discipline of the French Resistance in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows (1969).

Somehow, The Great Escape manages to mourn the dead and uphold a unified sense of defiance in the same movement. However unlikely, it pays respect to those who died, champions those who continued to fight against the enemy, and presents an anti-authoritarian message to boot. If the film can be accused of ignoring the genocide of World War II, it at least hatched an homage that, in a way, confronts the Holocaust. Chicken Run (2002), an Aardman stop-motion animated picture that draws influence (and Berstein’s score) from The Great Escape, uses a similar scenario to address mass murder. By setting the story on a chicken farm, the animals must escape to avoid becoming processed like Nazi victims in so many gas chambers. But the legacy of The Great Escape is not a grievous or sorrowful one, as Crowther might have hoped in his pleas for realism; rather, it lies in the psychological compartmentalization that allowed these POWs to not lose themselves to the crushing reality of war or their own capture—a struggle Sturges details when one prisoner commits suicide by guard. The great escape, then, is an inspiring message about realizing that all prisons remain temporary, and detainment is a state of mind.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your support, Jay!)

Bibliography:

Brickhill, Paul. The Great Escape. Norton, 1950.

Cull, Nicholas J. “Great Escapes: Englishness and the Prisoner of War Genre.” Film History, Vol. 14, 2002.

Lovell, Glenn. Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges. University of Wisconsin Press, 2008.

O’Malley, Shiela. “The Great Escape: Not Caught.” Criterion.com. 12 May 2020. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6941-the-great-escape-not-caught. Accessed 15 November 2020.

Schrafstetter, Susanna. “’Gentlemen, the Cheese Is All Gone!’ British POWs, the ‘Great Escape’ and the Anglo-German Agreement for Compensation to Victims of Nazism.” Contemporary European History, vol. 17, no. 1, 2008, pp. 23–43. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20081389. Accessed 26 Nov. 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review