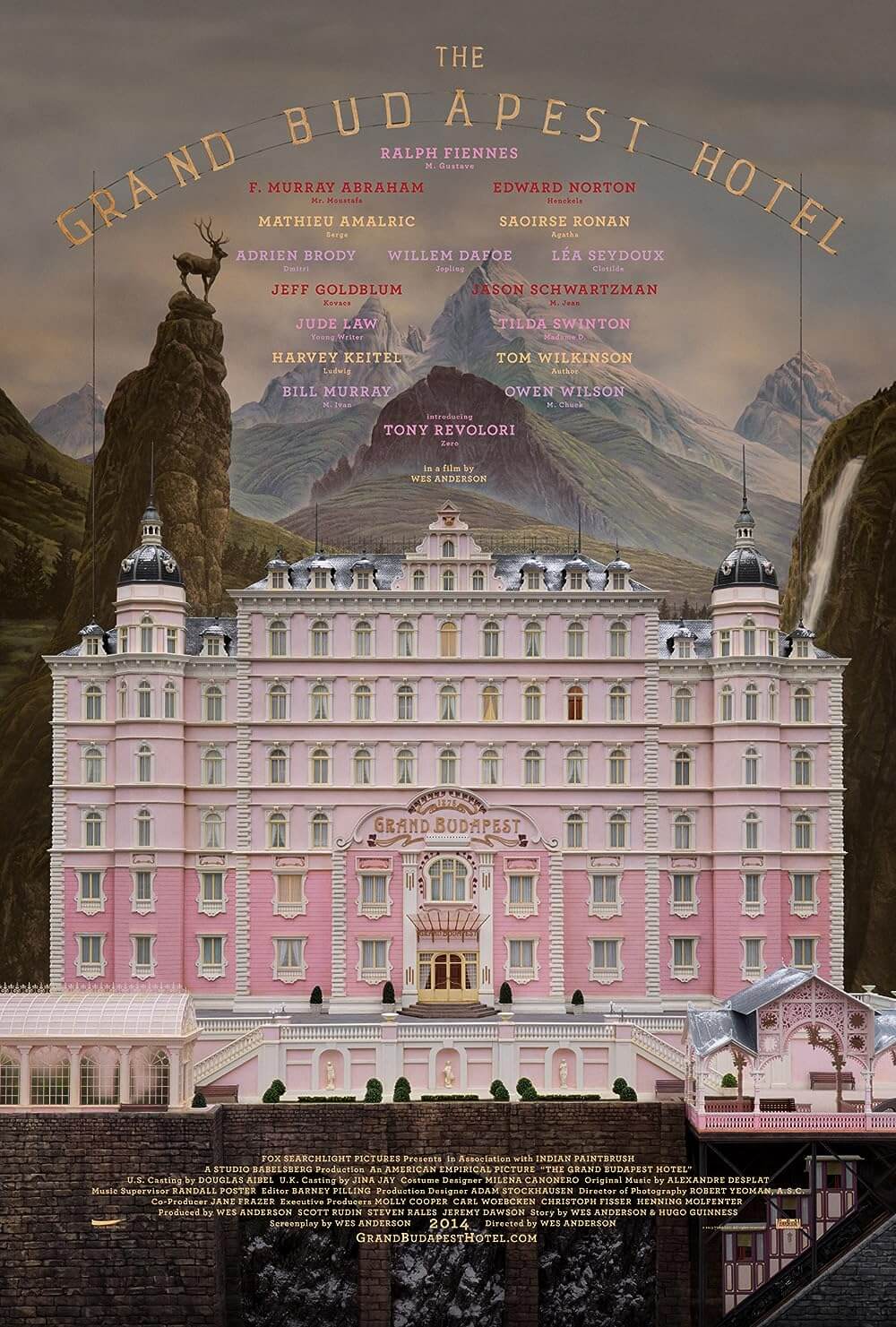

The Grand Budapest Hotel

By Brian Eggert |

In his memoir, The World of Yesterday, Viennese author and pacifist Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) wrote about his experiences witnessing and surviving the atrocities of World War I. Zweig noted, in the midst of his observations on the death around him, how the people of Budapest had not been gravely affected by any sense of impending doom as so many other European cities had. They maintained an air of elegance in times of fear and strife, and Zweig described their relatively carefree attitude, which was immersed in otherwise unimportant trifles such as well-dressed gentlemen and ladies, the loveliness of certain flowers, fine automobiles, and formal courtship etiquette. From this and other Zweig writings, filmmaker Wes Anderson found the credited basis for The Grand Budapest Hotel, a film immersed in the sophisticated refinement of and nostalgia for a bygone era. And while it contains all the idiosyncratic humor and unique stylistic vision of Anderson’s most pronounced works, the picture’s melancholy fondness for a more distinguished time doesn’t ignore the uglier aspects either.

Anderson searches with comic sadness for, as one of his characters observes, “a glimmer of civilization in the barbaric slaughterhouse we know as humanity.” As a filmmaker, he employs formal techniques used in the medium in the 1930s and beyond, while as a storyteller, he references early directors, everyone from Alfred Hitchcock to Fritz Lang to Ernst Lubitsch. But The Grand Budapest Hotel does not merely celebrate old-fashioned decorum; rather, Anderson celebrates and admires, like Zweig did, his characters’ ability to sustain that decorum through the worst of times. Of course, Anderson’s picture doesn’t occupy an aching seriousness. This is the director of Rushmore, The Darjeeling Limited, and Moonrise Kingdom, after all, and accordingly, the film is an absurdist comedy, which also takes the shape of a human drama while also containing elements of a caper, Wrong Man thriller, and love story all at once. But as audiences have come to expect from Anderson—and we haven’t been let down yet—his filmmaking is uncommonly funny, beautifully designed, and above all, resonates long after it’s over.

Leap-frogging back through time, the film begins, much like The Royal Tenenbaums, with the opening of a book, this one called “The Grand Budapest Hotel” and written by a venerated author (Tom Wilkinson). For his book’s 1985 introduction, the author claims everything he has written is “exactly as it happened,” and then we’re transported back to 1968 when his younger self (now Jude Law) visited the once-modish hotel of the title, in the fictional Republic of Zubrowka, during its shabby, communist-era downswing. He’s invited to dinner by the resort’s owner, Mr. Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham), and told Moustafa’s story, which begins in 1932. The dignified and elusive proprietor was once just a fresh-faced lobby boy named Zero (now played by Tony Revolori), a refugee of the world with the advent of “papers please” and passports in the years following the First World War. In those days, the Grand Budapest was a shining example of classiness, known throughout the world for the staff’s pristine treatment of its elite clientele.

Zero Moustafa’s story revolves around his mentor, Gustave H. (Ralph Fiennes, brilliant), a proper British chap and an exacting concierge who demands absolute obedience from his staff. Behind a debonair mustache and impeccably cut jib, Gustave is devoted to his guests and considers the reputation of the hotel before all else, giving sermons to the hotel staff during their rushed lunch break. And, though dignified and superior in his manners, when pressed outside the boundaries of the hotel Gustave is prone to vulgar bouts of foul language that provide a hilarious contrast to his distinguished self-conduct. Nevertheless, described later in the film, he is that “glimmer of civilization in the barbaric slaughterhouse we know as humanity.” He loves romantic poetry and douses himself with a scent called “L’air de Panache,” and he has a particular affection toward the pointedly older, blonde, rich women who visit his hotel, and very often, his services include bedding them. One of his most devoted patrons, the aged and flush Madame D. (Tilda Swinton, under a mountain of makeup), is murdered, and when Gustave is named in her will as the recipient of a priceless painting, her dastardly son Dmitri (Adrien Brody) and his bulldog-faced cutthroat Jopling (Willem Dafoe), clearly the culprits, frame Gustave for the murder.

From a comedy of sophistication, The Grand Budapest Hotel becomes a charming thriller in which Zero must use his mentor’s every instruction to keep him away from authorities and, after Gustave is eventually captured, help him escape and clear his name. Introduced are all manner of characters to help Zero, including his young lover, a pâtissier’s apprentice, Agatha (Saoirse Ronan), whose fate seems sealed within the exciting scenario if only because the elder Moustafa hesitates to speak of her. Countless characters deserve mention, but alas, Anderson has collected an incredible ensemble of actors whose roles can only be listed in a reasonably sized review: Mathieu Amalric, Jeff Goldblum, Bill Murray, Edward Norton, Jason Schwartzman, Owen Wilson, Harvey Keitel, Léa Seydoux, Larry Pine, Fisher Stevens, Waris Ahluwalia, Wallace Wolodarsky, and Bob Balaban—some of them onscreen for only a moment or two. Anderson’s rigorous eye for casting, not to mention aesthetics, has become increasingly detail-oriented, with The Grand Budapest Hotel standing as his most loaded, a don’t-look-away-for-a-minute-or-you’ll-miss-something array of visual stimuli.

Every frame is saturated with Anderson-isms now firmly established in his oeuvre: Title cards and chapter headings from a book; intentionally obvious use of miniatures, matte paintings, and soundstages; a lively Alexandre Desplat score; lateral tracking shots, quick zoom-ins and zoom-outs; and a careful dissection of each scene’s comic timing in the editing room. Though he relies on these customary, but by no means unwelcome or tiring practices, Anderson also evokes directors who made similarly themed tales in cinema’s Silent Age and early Talkies. A dashing cable car sequence pays homage to Carol Reed’s Night Train to Munich (1940), and a breakneck skiing chase recalls a scene from Hitchcock’s original The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934). In a sequence wherein Dafoe’s Jopling chases Goldblum’s lawyer character into a museum, Anderson uses the era’s high contrast shadows projected on the floor and walls and suspense worthy of Hitchcock himself. The stylistic flourishes don’t end with Anderson’s usual tricks; he also matches the aspect ratio of his film to that which was most popular in the setting: a boxy 1.37:1 to reflect the 1930s standard, 2.35:1 widescreen for the scenes in 1968, and a 1.85:1 to match the modern aspect ratio of widescreen televisions.

As with any Anderson film, after watching The Grand Budapest Hotel the viewer is overcome by a desire to gush about every detail they’ve witnessed. The production celebrates the respectability of this bygone era through Anderson’s unique and consistent vision. His Republic of Zubrowka is rich with color, its buildings, and décor (realized by Adam Stockhausen’s production design and Milena Canonero’s costumes), each recalling one of the elaborate pastries made by Agatha. More than in his other films, Anderson engages in a fabulous world, and here the harsh political background informs the quirky comedy found therein. In this sense, Anderson’s biggest influence in the film is Ernst Lubitsch, the inventor of the modern romantic comedy. Lubitsch released two of the funniest films ever made, yet each was a powerful statement confronting nationalism: in Ninotchka (1939), Greta Garbo played a Soviet agent whose icy communist exterior was melted by warm Parisian capitalism; in To Be or Not to Be (1942), Lubitsch made a comic farce about Polish actors outsmarting Nazis invaders.

No picture that contains this much visual, aural, emotional, film historical, and intellectual information and also remains so affecting could be anything less than a triumph. In a brief 99-minute runtime, Anderson encases a bewildering degree of significant themes, visual flourishes, and filmic touches into The Grand Budapest Hotel. And yet, even from a single viewing, an audience knows they have seen what surely must be one of Anderson’s best works to date, his style uniquely formed to a European sensibility from some 80 years ago, adeptly balancing his comedic identity with sudden moments of harsh violence attributable to the political turmoil going on outside of, and eventually inside, the cutoff world of the Grand Budapest. This is also Anderson’s most filmically aware picture, using influences abound without ever feeling unoriginal. What remains long after viewing, after lovingly recalling every fastidiously placed detail in Anderson’s production, is the film’s profound undercurrent of melancholy and eccentric joy for the distinguished past. Whether or not it was an elaborated story told and retold through various narrators, reliable or not, the story itself has a perfect balance of reality blended into Anderson’s signature whimsy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review