Reader's Choice

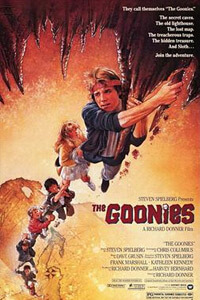

The Goonies

By Brian Eggert |

Watching The Goonies today is an exercise in nostalgia wrapped in more nostalgia. The movie brings back warm memories of Steven Spielberg’s heyday from the mid-1980s, when his cherished products, watched both in theaters and on our televisions on repeat, seared a permanent place in our collective consciousness. However formative The Goonies was on children growing up in the decade of excess, it was created as a reference machine, just as today’s movies and television shows now reference The Goonies ad nauseum. It pays homage to the same influences on Spielberg’s childhood that inspired his Indiana Jones films, everything from swashbucklers to Saturday matinee serials to the Belgian comic book The Adventures of Tintin (later directed by Spielberg in 2011). Made with equal parts clarity and the bustling energy of children, The Goonies contains old-fashioned ideas like pirate treasure maps and gold doubloons, yet it does so with a teenager’s modern sensibilities, a balance of skepticism and hope for the future. Today, it almost transcends criticism. One’s appreciation of it depends entirely on their subjectivity and personal fondness for the material. It’s a movie so omnipresent that the experience of watching it proves secondary to its irremovable place of our culture.

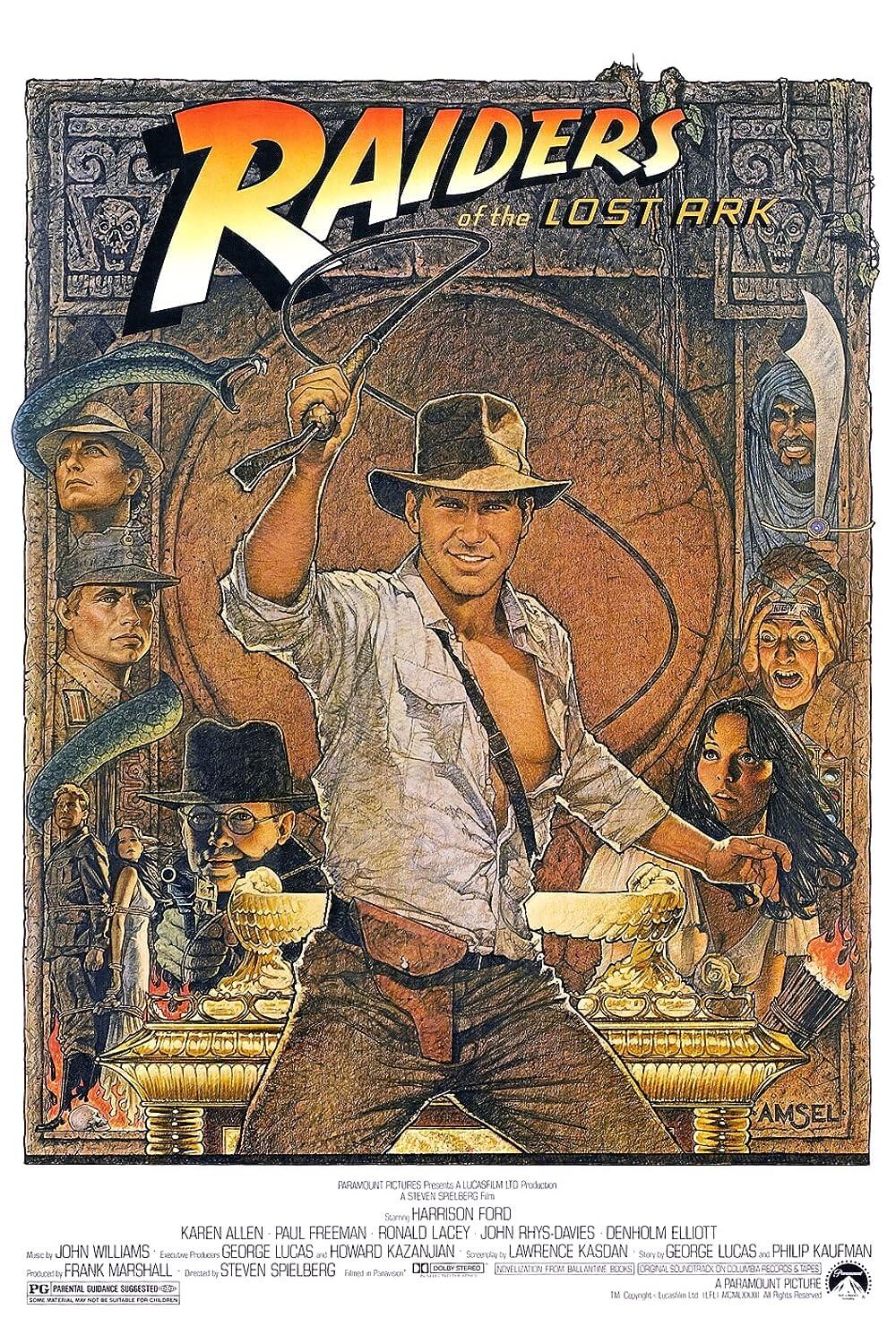

In 1985, the year The Goonies arrived in theaters, Time magazine featured a cover story called “Presenting Steven Spielberg: The Magician of the Movies.” Spielberg was at the height of his popularity after Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). But he turned down countless offers, including a chance to run Disney, to focus on his own production company, Amblin Entertainment. The company’s brand dominated pop culture of the 1980s, while the Amblin logo—a boy riding a bike through the sky in an image borrowed from E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), then the highest-grossing film ever made—became a symbol of imagination, adventure, and material that appealed to both children and adults. During this time, Spielberg oversaw and frequently contributed to Amblin projects helmed by other filmmakers, such as Tobe Hooper on Poltergeist (1982); John Landis, Joe Dante, and George Miller on Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983); Dante again on Gremlins (1984); and Robert Zemeckis on Back to the Future (1985). Spielberg even found his way onto televisions with his NBC anthology series Amazing Stories, where filmmakers ranging from Martin Scorsese to Tom Holland to Brad Bird captured the appeal of science-fiction magazines from the 1950s and 1960s. Spielberg had established a Hollywood empire, and The Goonies arrived at the Pax Spielbergana.

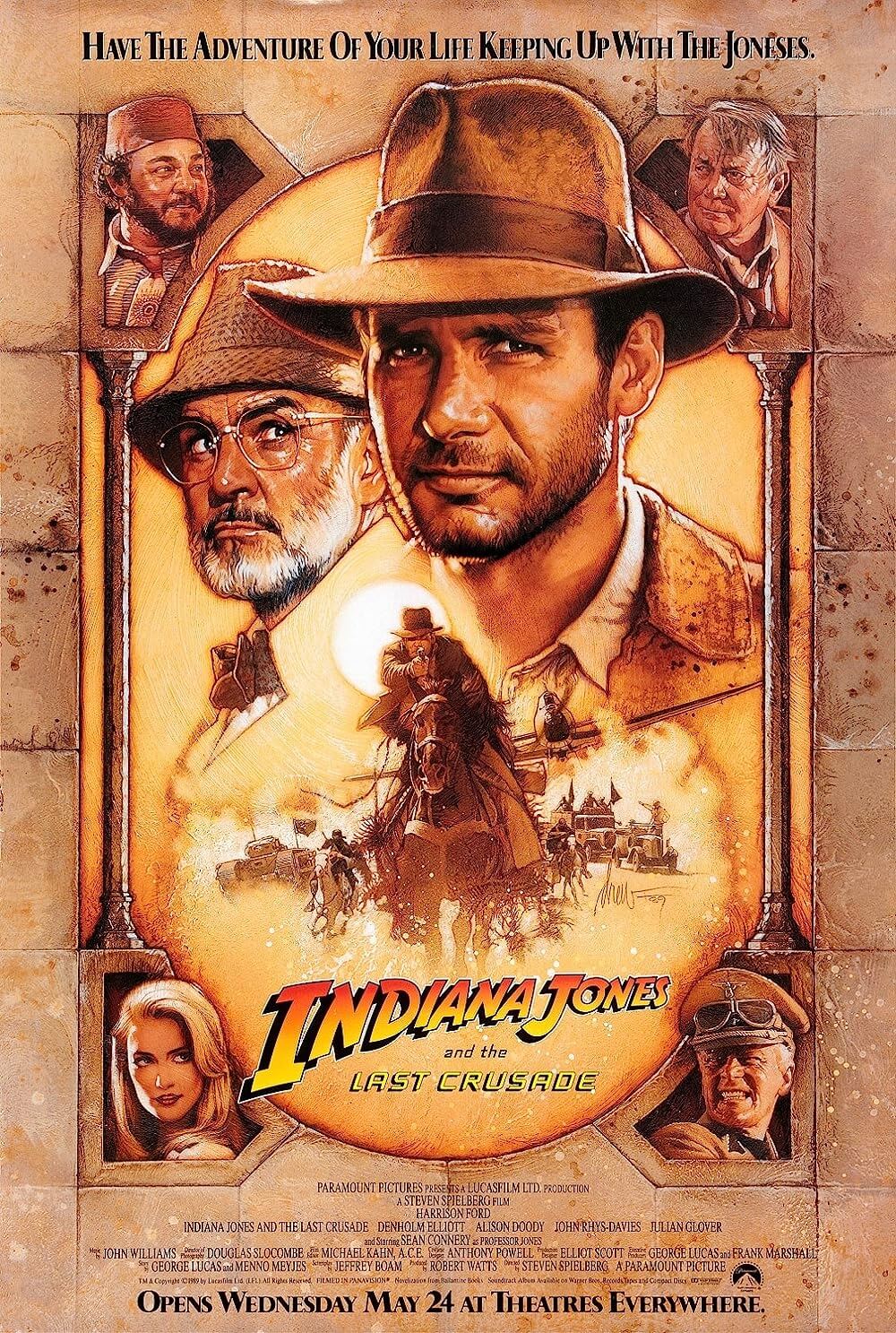

Most Amblin projects relied on nostalgia, the driving force of so many popular works by New Hollywood directors who emerged in the 1970s. George Lucas pined for the past with American Graffiti (1973) and reenvisioned Flash Gordon serials from the 1930s with Star Wars (1977). Lucas and Spielberg also conceived of Indiana Jones from Saturday matinee adventures. Brian De Palma all but rebirthed Alfred Hitchcock’s style in films like Sisters (1973) and Dressed to Kill (1980). Zemeckis epitomized the back-to-the-fifties obsession with Back to the Future and I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978). Similarly, The Goonies draws from classic pirate adventures such as the Errol Flynn swashbuckler Captain Blood (1935), as well as the boyhood mystery series The Hardy Boys, both referenced in the movie. Although Amblin’s output during this period could be described as overly reliant on the past, Spielberg’s unique treatment allowed the material to connect with audiences then and now. His ideas may come from sources that echo from his childhood, but he retells familiar stories in ways that acknowledge a crossover between adults and children. Spielberg was often described as an adult-sized teenager at the time. And so, Amblin movies are scarier and more thematically intense versions of your average PG-rated family fare—so intense, in fact, that Spielberg petitioned the MPAA to launch the PG-13 rating to accommodate such middle-ground pictures. His movies acknowledge that some children have darker interests than sunshine and rainbows; they also enjoy monsters, pirates, and hidden treasure with a kind of innocent curiosity in the macabre.

Most Amblin projects relied on nostalgia, the driving force of so many popular works by New Hollywood directors who emerged in the 1970s. George Lucas pined for the past with American Graffiti (1973) and reenvisioned Flash Gordon serials from the 1930s with Star Wars (1977). Lucas and Spielberg also conceived of Indiana Jones from Saturday matinee adventures. Brian De Palma all but rebirthed Alfred Hitchcock’s style in films like Sisters (1973) and Dressed to Kill (1980). Zemeckis epitomized the back-to-the-fifties obsession with Back to the Future and I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978). Similarly, The Goonies draws from classic pirate adventures such as the Errol Flynn swashbuckler Captain Blood (1935), as well as the boyhood mystery series The Hardy Boys, both referenced in the movie. Although Amblin’s output during this period could be described as overly reliant on the past, Spielberg’s unique treatment allowed the material to connect with audiences then and now. His ideas may come from sources that echo from his childhood, but he retells familiar stories in ways that acknowledge a crossover between adults and children. Spielberg was often described as an adult-sized teenager at the time. And so, Amblin movies are scarier and more thematically intense versions of your average PG-rated family fare—so intense, in fact, that Spielberg petitioned the MPAA to launch the PG-13 rating to accommodate such middle-ground pictures. His movies acknowledge that some children have darker interests than sunshine and rainbows; they also enjoy monsters, pirates, and hidden treasure with a kind of innocent curiosity in the macabre.

The first image of The Goonies is a massive death’s head that fills the screen, as if to say, “Here be a warning to all ye who enter.” This symbol of pirates and poison signals the somewhat dark thematic material that will follow, such as the first scene that finds Italian crook Jake Fratelli (Robert Davi) seemingly dead in a prison cell after hanging himself. He’s faking, of course, but the image is a shocker in a so-called family-friendly entertainment, and it will not be the last image from The Goonies that pushes boundaries. Jake’s brother Francis (Joe Pantoliano) and their sandpaper-voiced Mama (Anne Ramsey, channeling Margaret Wycherly’s “Ma” Jarret from 1949’s White Heat) have planned a jailbreak. The ensuing police chase over the opening credits passes by each of the titular Goonies, the name a group of oddball and reject teenagers in Astoria, Oregon, have given to themselves. The characters are not complex, but each one appeals to a distinct demographic, and thus, everyone has a favorite Goonie: Sean Astin is the idealistic dreamer Mikey, the most Spielbergian of the bunch. Josh Brolin is the macho brother Brand. Corey Feldman is the wiseacre Mouth. Jeff Cohen is the comic relief scaredy-cat Chunk. Ke Huy Quan is Data, a combination of James Bond and his gizmo-supplier, Q. Girls are late additions to the gang, supplying limited tropes with Kerri Green as the cheerleader Andy and Martha Plimpton as the tomboy Stef.

Spielberg conceived of The Goonies while working on The Color Purple (1985), his film based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Alice Walker that was supposed to establish him as capable of more than giant sharks, Nazi-fighting adventurers, and kindly aliens. He hired Gremlins screenwriter Chris Columbus to develop his idea into a script, and he told Richard Corliss in Time magazine that The Goonies was “a film I didn’t want to direct but I did want to see, so I asked Richard Donner to do it.” Donner, the director of Superman (1978) and Superman II (1980), and by all accounts a consummate professional, could handle a large-scale production and adapt to Spielberg’s many notes. To be sure, besides his status as Amblin’s mogul, Spielberg had what David Blum in New York Magazine called “mentor complex,” which found him shaping other filmmakers according to his own impulses. As a result, many critics at the time saw Spielberg as the auteur behind the production, not Donner. Gene Siskel called The Goonies “a Spielberg parody” and noted how the movie’s villains resemble those in the Spielberg-produced Poltergeist—ruthless land developers who plan to buy up Astoria and turn it into a golf course. (But given both Spielberg and Columbus’ affinity for Classic Hollywood tropes, it’s more likely that the evil bankers were a nod to the cruel Mr. Potter from It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), also referenced in Columbus’ script for Gremlins.) In any case, Donner tried to discourage the producer’s hands-on influence, but Spielberg would end up filming several second unit shots and contributing to the look and feel of the production. Doubtless, it was Spielberg’s brand name that helped earn The Goonies more than three times its $19 million budget at the 1985 box office.

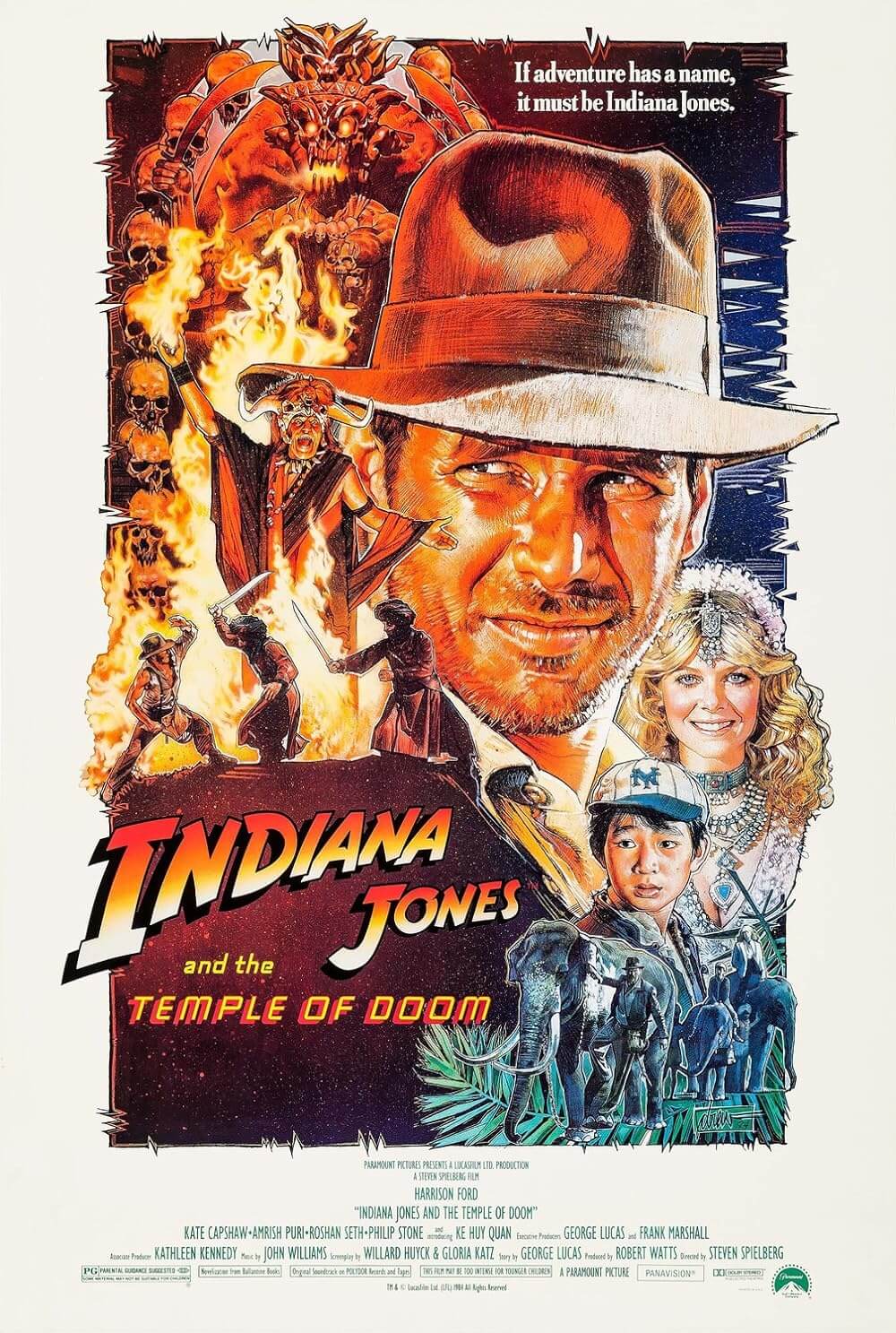

Sure enough, The Goonies contains more Spielberg signatures than any quality attributable to Donner’s otherwise confident and capable work as a journeyman (The Omen, Lethal Weapon, et al.). Neal McLean, who served as a camera operator on Spielberg’s The Sugarland Express (1973) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, knew the Spielberg aesthetic and carried that into many of The Goonies’ sequences. The production shot on location in Astoria, an idyllic Small Town, USA, giving the movie its personality in the early scenes. But McClean’s most Spielbergian flourishes appear in the underground cave sequences. Captured on soundstages and under controlled conditions, McClean uses rich lighting, blue-sparkling water, and glimmering treasure straight out of an Indiana Jones adventure. Indeed, The Goonies never hides its replication of the Indiana Jones model. Like Harrison Ford’s iconic hero, the child misfits follow clues to a secret treasure hidden in a cave system by a pirate named One-Eyed Willy. Just as Indiana Jones faces Nazis on his quest, the Goonies face the Fratellis, who have their hands in everything from murder to counterfeiting. In one scene, the Goonies enter a skull-shaped cave with passageways illuminated by orange light—imagery that feels lifted from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). Along the way, our young heroes face deadly booby traps in the form of rolling boulders, floors that fall away, and falling rocks. Sound familiar? Indiana Jones races through caves on a veritable roller coaster; the Goonies race through caves on a water slide. Still, the historical background of Raiders of the Lost Ark and infamously horrific gore in Temple of Doom may have repelled children, whereas The Goonies offered its audience a cast of familiar youngsters.

Sure enough, The Goonies contains more Spielberg signatures than any quality attributable to Donner’s otherwise confident and capable work as a journeyman (The Omen, Lethal Weapon, et al.). Neal McLean, who served as a camera operator on Spielberg’s The Sugarland Express (1973) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, knew the Spielberg aesthetic and carried that into many of The Goonies’ sequences. The production shot on location in Astoria, an idyllic Small Town, USA, giving the movie its personality in the early scenes. But McClean’s most Spielbergian flourishes appear in the underground cave sequences. Captured on soundstages and under controlled conditions, McClean uses rich lighting, blue-sparkling water, and glimmering treasure straight out of an Indiana Jones adventure. Indeed, The Goonies never hides its replication of the Indiana Jones model. Like Harrison Ford’s iconic hero, the child misfits follow clues to a secret treasure hidden in a cave system by a pirate named One-Eyed Willy. Just as Indiana Jones faces Nazis on his quest, the Goonies face the Fratellis, who have their hands in everything from murder to counterfeiting. In one scene, the Goonies enter a skull-shaped cave with passageways illuminated by orange light—imagery that feels lifted from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). Along the way, our young heroes face deadly booby traps in the form of rolling boulders, floors that fall away, and falling rocks. Sound familiar? Indiana Jones races through caves on a veritable roller coaster; the Goonies race through caves on a water slide. Still, the historical background of Raiders of the Lost Ark and infamously horrific gore in Temple of Doom may have repelled children, whereas The Goonies offered its audience a cast of familiar youngsters.

Nevertheless, there’s plenty about The Goonies that remains surprisingly edgy, if not eyebrow-raising today: On the Spanish-speaking maid, Mouth plays crude practical jokes that discuss hardcore drugs and sex toys; Andy wears a questionably short skirt; Chunk’s entire identity is a fat-shaming device; and there’s some racial stereotyping of Italian and Chinese cultures. The dysfunctional Fratellis are another beast altogether. They keep a dead body in the ice cream freezer and torture the young Chunk for information. Ramsey, who reportedly smelled of bourbon on the set most of the time, plays the abusive mother of an oft-dropped son, Sloth (ex-football player John Matuszak), who resembles Charles Laughton’s version of the Hunchback of Notre Dame. The poor man, dubbed “It” and “the monster” at various points, is shackled with chains Mama acquired at a zoo, and he’s left in a dark room with nothing but a television to keep him company. To my knowledge, we never learn his birth name. Unlike the other Goonies, Sloth is never more than his nickname, an Other. Then again, Sloth is often a fan favorite, and his bellowed line (“Hey you guys!”), borrowed from Chunk, becomes rather endearing. In a way, The Goonies does what Spielberg did best in the 1980s—he brings his audience to the brink by testing the established boundaries, but always in a way that feels safe.

It’s a testament to Donner and Spielberg, who let the kids be kids on the set, that this band of outsiders makes the audience feel like one of their group. Their kinship and clamorous behavior feel natural. But the child-friendly atmosphere of The Goonies, according to Spielberg’s detractors, is exactly the problem. It’s an early example of Spielberg borrowing from himself for a more palatable product. If Jurassic Park (1993) was simply a new kind of Jaws, as some have argued, and Ready Player One (2018) was full of self-indulgent references to his own oeuvre, then The Goonies seems like little more than a family-centric Indiana Jones, and it comes from the same misguided impulse that led to Spielberg (wrongly) apologizing for the bloodshed in Temple of Doom. Pauline Kael, who supported Spielberg’s earlier efforts such as The Sugarland Express in her New Yorker reviews, later questioned the industry-wide implications of his empire: “It’s not so much what Spielberg has done as what he has encouraged. Everyone else has imitated his fantasies, and the result is an infantilization of the culture.” Though one can hardly blame Spielberg for how other filmmakers imitate him, the Amblin movies he produced behind other directors tend to feel like knock-offs. Stuff like Poltergeist or Batteries Not Included (1987) feel as though Spielberg was controlling what happened behind the scenes, whereas only the occasional Dante or Zemeckis picture would emerge from the Amblin label and feel like the voice of a distinct auteur, though also vaguely Spielbergian. David Lean, the director of The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and a major influence on Spielberg, defended him. “He just loves making films,” Lean said. “He is entertaining his teenage self—and what is wrong with that?”

If one’s reception of The Goonies depends on one’s subjectivity, as I have suggested, then perhaps I should remark about my own experiences. Although The Goonies was always on television when I was a child, I enjoyed it less than other Spielberg-brand adventures. Personally, I have always preferred the dangerous fantasies of Indiana Jones, while the constant arguing of Astoria’s Goon Docks gang has tested my patience. That patience ran out when I worked in a video store as a teenager, and The Goonies was one of several titles that played on a loop. This is an endurance test for any film. Can it withstand daily viewings for months on end? It can, but not without some considerable side effects. Repeated viewership of any film results in either a white noise effect or an aggrandization through cult obsession. Without question, many have watched The Goonies over and over, and their viewership has deepened their love and appreciation for the movie’s many strengths. After a recent viewing, I understand why the movie’s legacy continues to this day, but I have no passion for anything happening onscreen. The Goonies is neither a warm blanket of nostalgia nor a reunion with old friends. My own overexposure has produced the movie equivalent to snow blindness, where I can no longer see The Goonies beyond its frequently quoted dialogue and general oversaturation in our culture.

The Goonies has flourished over the years as a fan favorite more than a critical darling. Its persistent cult following to this day means that merchandise (t-shirts, lunchboxes, toys, etc.) is still readily available, and over the last two decades, rumors about a sequel have continued to no avail. Its blueprint led to dozens of copycats at the time, such as the more durable Stand by Me (1986) and The Monster Squad (1987), while a new generation of filmmakers has embraced their nostalgia by paying homage. The Duffer Brothers built a sizable niche with their reference-laden Netflix series Stranger Things, which features the same formula of lovable outcasts and rambunctious energy as The Goonies. Also, Andy Muschietti’s adaptation of Stephen King’s It owes much to the Altman-style overlapping dialogue of The Goonies, complete with kids bickering at one another in an underground cave system. But if the movie’s background teaches us anything, it’s that our culture’s obsession with nostalgia is nothing new. While middle-aged generations look back fondly on The Goonies, Spielberg and the other filmmakers looked back on swashbucklers and treasure-hunting mysteries from their own childhoods. How appropriate that the story itself is about looking back and uncovering the jewels of the past, and finding new ways to savor that which would be forgotten unless we remember its many wonders.

(Editor’s Note: Thanks to Aaron, who suggested and commissioned this review on Patreon!)

Bibliography:

Blum, David. “Steven Spielberg and the Dread Hollywood Backlash.” New York Magazine. 24 March 1986, pp. 52-55.

Byrne, Wayne, and Nick McLean. Nick McLean Behind the Camera: The Life and Works of a Hollywood Cinematographer. McFarland and Co., 2020.

Corliss, Richard. “Show Business: I Dream for a Living.” Time. 15 July 1985, pp. 52-56.

Friedman, Lester D. Citizen Spielberg. University of Illinois Press, 2006.

McBride, Joseph. Steven Spielberg (Third Edition). Faber and Faber, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review