Reader's Choice

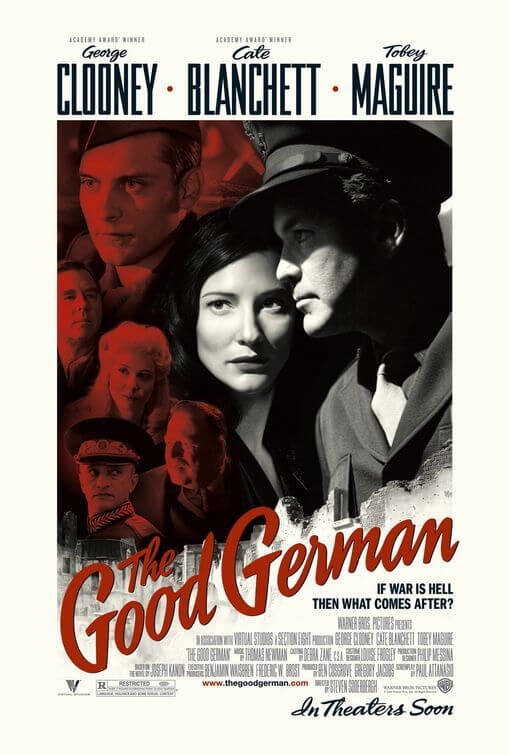

The Good German

By Brian Eggert |

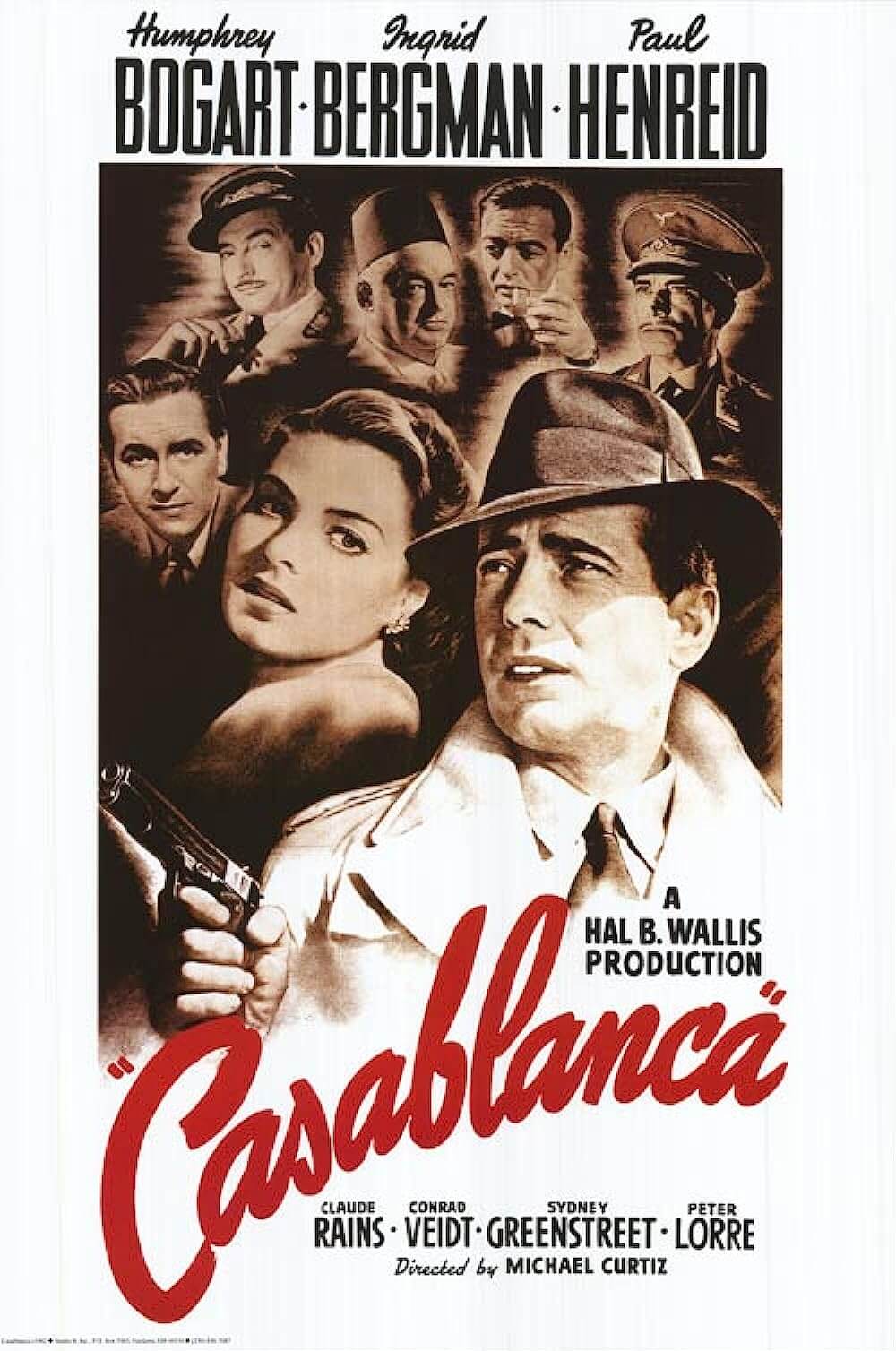

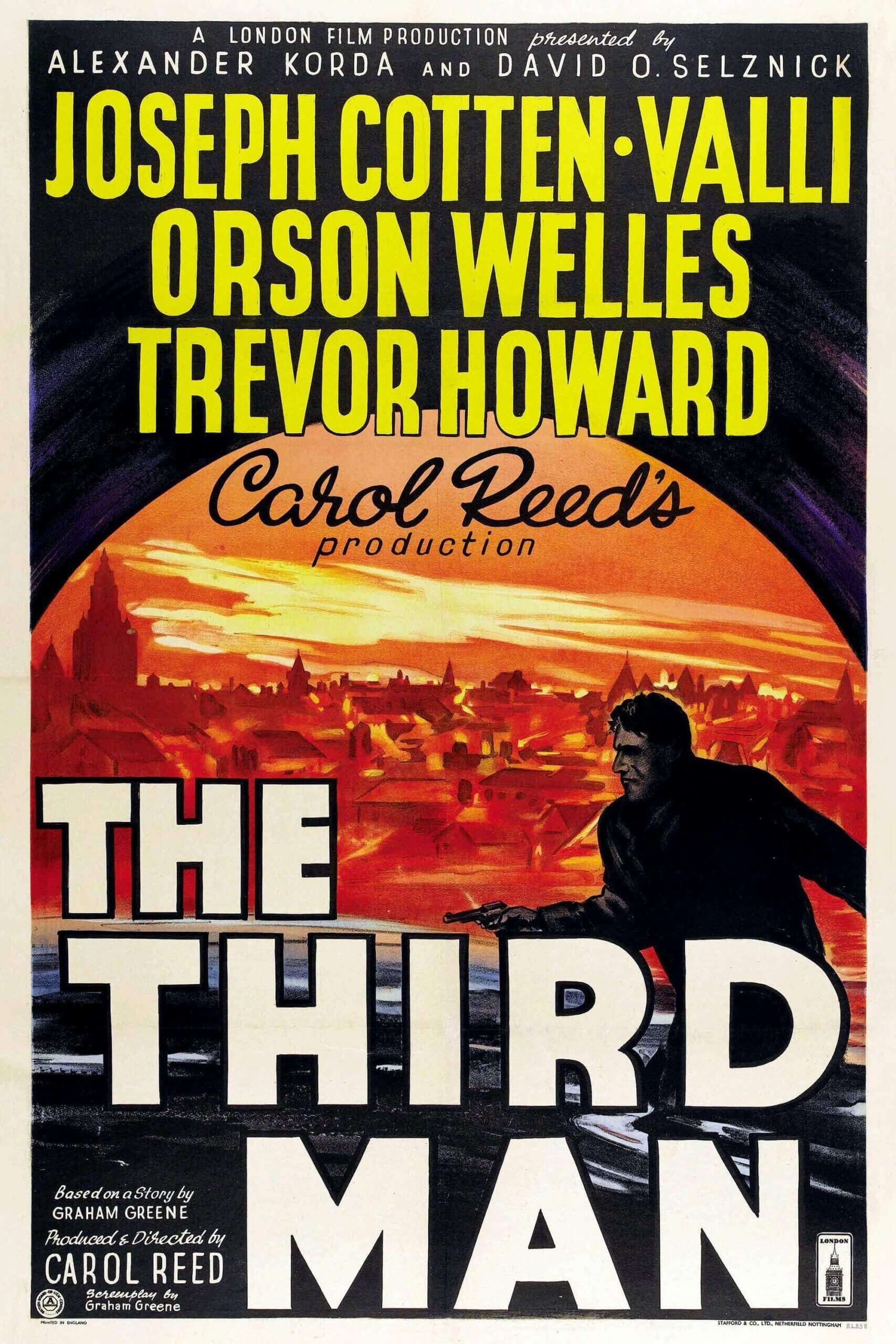

The Good German is among Steven Soderbergh’s most daring experiments, though it’s not an altogether successful one. The artistic question driving the production is this: What would it look like if the Hays Code had not restricted a classical Hollywood production? Could the formal techniques from the 1940s be used to explore the grim reality, compromised morality, brutal violence, and sexuality of postwar Berlin? “It will be interesting to see if people can wrap their minds around the blending of these two ideas,” Soderbergh said in press notes. Although each element of The Good German’s presentation recalls visual, audio, and narrative components used in 1940s films set during and after the war—specifically Casablanca (1942), A Foreign Affair (1948), and The Third Man (1949)—the material features subject matter that feels inappropriate for films made in that style, especially for audiences versed in the moral guidelines of classical Hollywood cinema. But while The Good German maintains Soderbergh’s interest in stories about the human cost of social injustice and corrupt institutions, his aesthetic gamble doesn’t always pay off as well as it should have dramatically. The resulting pastiche is an admirable, at times ungainly, yet always compelling film that must be admired for existing at all.

Soderbergh tells the story in black-and-white photography, serving, as usual, as his own cinematographer under his pseudonym, Peter Andrews. He employs lenses from the 1940s and a boxy 1.33:1 aspect ratio to match. He adopts a noirish style of high contrasts, bold shadows, and the illusion of rear-projected driving scenes like those from the era—even though they were derived from German Expressionists working in the 1910s to 1930s. Some modern technologies, such as wireless mics, went unused in favor of the era’s boom mics, requiring the actors to give broader performances. The director staged scenes with intentional choices around blocking, working like a filmmaker from the Golden Age with a limited amount of coverage, no close-ups, and few options in editing (Soderbergh edited the picture under his usual name, Mary Ann Bernard). Even the score by Thomas Newman sounds more like the music of his father, Alfred Newman, who composed dozens of Hollywood classics, beginning in 1930 and lasting four decades. The entire mise-en-scène engages in an intertextual and formal discussion about the history of media and representation, and it asks a broader question about America’s complicit role in war crimes. Yet, Soderbergh achieved some of the special effects shots with modern digital solutions, adding to the production’s conversation between the classical and the modern.

Based on Joseph Kanon’s 2001 novel of the same name, the story opens in Berlin around the Potsdam Conference that established European borders in the summer of 1945, about a month before Japan’s surrender. The political parties involved in the conference debate whether all of Germany should be tried as war criminals for Hitler’s indiscretions, while around them, the city remains a shattered skeleton of bombed buildings, streets filled with rubble, and citizens scraping by to survive. Not unlike postwar Vienna in The Third Man or Berlin in A Foreign Affair, the Black Market thrives. Those willing can exploit the locals’ desperation and earn a hefty profit, while everyone else turns a blind eye. George Clooney plays Captain Jake Geismer, an American military journalist for The New Republic sent to cover the conference. Shortly after his arrival, Geismer is drawn into a murder mystery and political conspiracy linking his German ex-lover, Lena Brandt (Cate Blanchett), and the killing of his appointed driver, Patrick Tully (Tobey Maguire). Like another cinematic Jake—Jack Nicholson’s Jake Gittes in the neo-noir Chinatown (1974), marking the first of many references to that Roman Polanski film—Geismer finds himself always a step behind and trying to expose powers beyond his control.

Most fascinating is Lena, who wants out of Berlin. She spends her time with Tully, who works for the American military motor pool. With access to incoming and outgoing shipments, Tully rakes in the dough by selling Black Market booze and other rare commodities to whomever he pleases. Maguire’s portrayal of Tully is crass and aggressive—a stretch for the creaky-voiced actor—and it’s suggested that he’s been unbridled by the corruptive powers of Berlin. Though his character’s hedonism is never fully explained, Lena suggests his behaviors amount to the actions of a “boy.” Jake becomes personally involved when he discovers Tully and Brandt are now lovers, but he doesn’t realize they’re only lovers because Lena is using him. In an allusion to Marlene Dietrich’s character in A Foreign Affair, Lena uses everyone. She sells herself to survive and endures Tully even though he beats her. She will do anything to survive and eventually get out of Berlin, just as she did anything to survive the war, which includes marrying a Nazi, despite being Jewish. Lena doesn’t take pride in this behavior; it’s simply a fact of life in wartime and postwar Berlin—you do what you must to survive.

Most fascinating is Lena, who wants out of Berlin. She spends her time with Tully, who works for the American military motor pool. With access to incoming and outgoing shipments, Tully rakes in the dough by selling Black Market booze and other rare commodities to whomever he pleases. Maguire’s portrayal of Tully is crass and aggressive—a stretch for the creaky-voiced actor—and it’s suggested that he’s been unbridled by the corruptive powers of Berlin. Though his character’s hedonism is never fully explained, Lena suggests his behaviors amount to the actions of a “boy.” Jake becomes personally involved when he discovers Tully and Brandt are now lovers, but he doesn’t realize they’re only lovers because Lena is using him. In an allusion to Marlene Dietrich’s character in A Foreign Affair, Lena uses everyone. She sells herself to survive and endures Tully even though he beats her. She will do anything to survive and eventually get out of Berlin, just as she did anything to survive the war, which includes marrying a Nazi, despite being Jewish. Lena doesn’t take pride in this behavior; it’s simply a fact of life in wartime and postwar Berlin—you do what you must to survive.

Unfolding in labyrinthine fashion at a flat, measured pace, the conspiracy at the heart of the film finds Soderbergh once more exposing the self-interested and moral corruption of institutions, specifically the American government. Paul Attanasio’s knotty script details an elaborate cover-up to conceal proof that a valuable German scientist used slave labor to develop the V-2 rocket and worked at the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. Lena’s husband, Emil (Christian Oliver), has proof of the scientist’s war crimes, which, if exposed, would prevent the American government from employing him to develop rockets for its military. Emil is eventually murdered, and though Geismer retains Emil’s documented proof of the scientist’s crimes, Geismer trades the information to get Lena out of Berlin—in a detail echoing Casablanca’s letters of transit. While fictional, the story draws from the true story of Arthur Rudolph and Wernher von Braun, who hatched deals with the American government to build rockets for NASA to avoid any consequences for their roles in Nazi concentration camps. America’s collusion with Nazi scientists would never be the subject of a classical Hollywood film, and Soderbergh deploys the theme to rethink history and form in an alternative context.

Audiences didn’t respond to Soderbergh’s conceit, despite the star-studded cast. The Good German earned a mere $6 million on a $32 million budget. Likewise, most critics dismissed the film upon its release in 2006, claiming the plot was too complicated to follow and the approach too experimental. Sure, the story involves murder, conspiracies, wartime horrors, and the A-Bomb, but it’s no more confusing than the classics from which it derives influence. Regardless, the best mysteries aren’t about the details; they’re about how well they involve you in the search for answers. Clooney’s performance as Jake has been compared to Humphrey Bogart’s Rick from Casablanca, except, unlike Bogart, the script doesn’t allow for Clooney to develop into an engaging character, Clooney’s charms notwithstanding. Audiences have loved Rick for over 80 years; it’s difficult to imagine anyone loving Jake beyond the end credits. In Casablanca, Rick becomes endearing only after flashbacks that explain his history with Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman). Because we see sections of Rick and Ilsa’s past romance, we care about their future. Jake, conversely, is a one-note character whose past remains uncertain, and his only drive is the desire to solve a mystery. The film shows us mere pebbles of Jake’s personal life. His alleged love for Lena is never described, so the audience doesn’t understand why this mystery is so important for Jake to solve.

Perhaps it’s her humanist intentions, the mystery around her motivations, or her sordid Nazi associations and past, but Blanchett’s Lena Brandt brings a pulpy quality to The Good German, which is otherwise absent from the film. She’s at once the most interesting and troubling character onscreen. Looking like Lauren Bacall, Blanchett delivers each line in a perfect deep German accent in song with Marlene Dietrich—to the extent that the performance feels pieced together by imitations of other performers to distracting effect. Still, the material allows Blanchett to emerge from behind the clear influence of her predecessors. Like Jake, Lena is driven by a single desire, and she’s capable of anything. There’s something so urgent and desperate about her struggle that we can’t help but empathize with her, even after she confesses to selling out her fellow Jews to the Gestapo to survive. Is Lena a victim of circumstance, just someone who happened to be born in the wrong country—Germany—at the wrong point in history? Is she a killer? A Nazi? Can the audience, more specifically Jake, judge her for her actions, given her desperate situation? Can anyone survive in Germany in the 1940s without becoming a criminal or compromising their morals? “You can never really get out of Berlin,” says Lena, in a line reminiscent of the famous one that concluded Chinatown.

Perhaps it’s her humanist intentions, the mystery around her motivations, or her sordid Nazi associations and past, but Blanchett’s Lena Brandt brings a pulpy quality to The Good German, which is otherwise absent from the film. She’s at once the most interesting and troubling character onscreen. Looking like Lauren Bacall, Blanchett delivers each line in a perfect deep German accent in song with Marlene Dietrich—to the extent that the performance feels pieced together by imitations of other performers to distracting effect. Still, the material allows Blanchett to emerge from behind the clear influence of her predecessors. Like Jake, Lena is driven by a single desire, and she’s capable of anything. There’s something so urgent and desperate about her struggle that we can’t help but empathize with her, even after she confesses to selling out her fellow Jews to the Gestapo to survive. Is Lena a victim of circumstance, just someone who happened to be born in the wrong country—Germany—at the wrong point in history? Is she a killer? A Nazi? Can the audience, more specifically Jake, judge her for her actions, given her desperate situation? Can anyone survive in Germany in the 1940s without becoming a criminal or compromising their morals? “You can never really get out of Berlin,” says Lena, in a line reminiscent of the famous one that concluded Chinatown.

The sheer potency of Lena’s character would have never survived the Hays Code of 1930, nor would most of the film. The Hays Code had three General Principles: 1) the movie should not lower the morals of moviegoers or encourage wrongdoing, 2) the movie should portray the “correct standards of life” as determined by the Code’s enforcement division, and 3) law should always be respected and enforced. Motion pictures from the Golden Age often circumvented these principles by fooling the review board with clever dialogue, metaphors, and historical analogies. But in The Good German, graphic sex, vulgar language, and bloody violence all appear without restraint—an exception not only for classical Hollywood cinema but also for Soderbergh’s films. The director seems to amplify scenes of sexuality or violence to highlight their incongruity within a classical presentation. The tactic feels overemphasized and occasionally unnatural. Similarly, Soderbergh often relies too heavily on allusionism, replicating iconic scenes, such as modeling his final scene at the airport after the analogous one in Casablanca. Even The Good German’s movie poster bears an unmistakable resemblance to Casablanca’s, which begins to feel like Soderbergh was less inspired by classics than stealing from them outright.

With its winks at wartime thrillers, film noirs, and neo-noirs, The Good German spends much of its time in reference mode. Soderbergh’s visual and aesthetic homages to classic Hollywood and even New Hollywood cinema situate his film in a post-post-modern context, where he not only deconstructs and modernizes traditional narratives but reconfigures his formal approach into a conceptual interplay between various epochs of influence. The film might be one of Soderbergh’s last great experiments, which were more frequent in the first decade or so of his career—see Kafka (1991) and Schizopolis (1996)—when he often steeped his work in process, stylistic analysis, and bold narrative swings. But the average movie watcher could never randomly find The Good German streaming somewhere and appreciate its layers; Soderbergh hasn’t constructed it that way. And while some of his choices result in dissonance, that’s also the point. It’s not meant to be watched as a mere narrative; instead, it operates as a complex exchange between styles, stories, and the factors that influence them over time. If it’s not always successful as a scenario and sometimes leans too far into allusion, it’s nonetheless a fascinating project that demands more consideration than it was given in 2006.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on August 21, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Baker, Aaron. Steven Soderbergh. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

DeWaard, Andrew and R. Colin Tait. The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh: Indie Sex, Corporate Lies, and Digital Videotape. Wallflower Press, 2013.

Gallager, Mark. Another Steven Soderbergh Experience: Authorship and Contemporary Hollywood. University of Texas Press, 2013.

Kaufman, Anthony. Steven Soderbergh Interviews. Jackson University Press, 2002.

Palmer, R. Barton and Steven M. Sanders. The Philosophy of Steven Soderbergh. The University Press of Kentucky, 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review