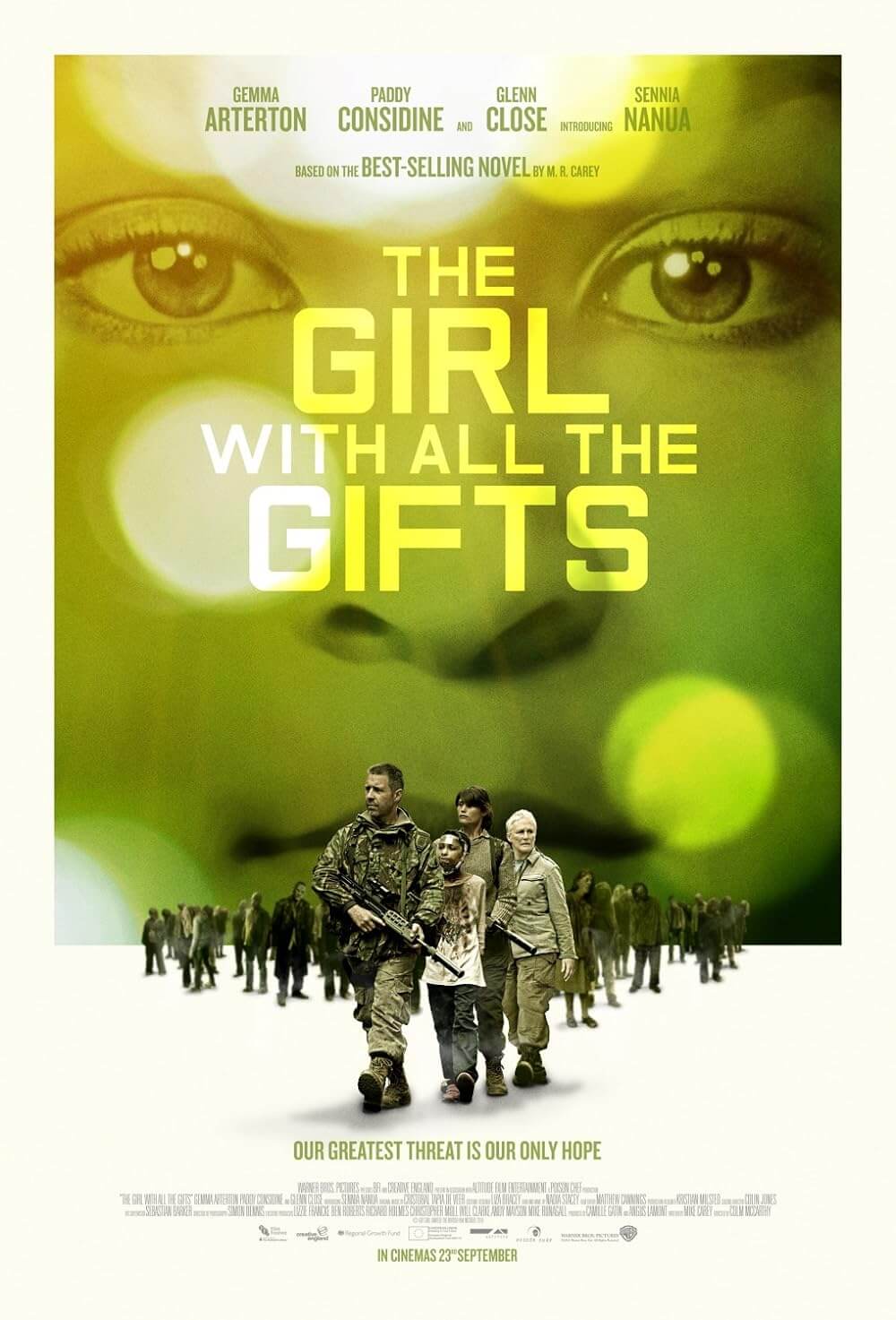

The Girl with All the Gifts

By Brian Eggert |

At the center of The Girl with All the Gifts resides a persistent irony that children, customarily presented as beacons of innocence who demand protection from adults, are treated like bloodthirsty killers. In an underground military bunker somewhere in the U.K., seemingly normal children are strapped to wheelchairs and escorted at gunpoint to a classroom where they’re given basic lessons. Occasionally, they receive a bowl of live worms for nourishment. They know nothing more than this existence, nothing of the outside world beyond going back-and-forth between an empty concrete cell to a spare classroom, all under chilly fluorescent lights and the frightened eyes of their keepers. The brightest among the children is Melanie (Sennia Nanua). She absorbs information easier than her fellow students and tries to engage with her dismissive guards, who treat her like a bomb that’s about to go off.

The driving irony of director Colm McCarthy’s film never subsides. And to Nanua’s credit, the viewer continues to see her as a child, even after we realize she’s a “hungry”—the film’s version of a zombie. Set twenty years after a post-apocalyptic event, the film, adapted by Mike Carey from his own 2014 novel, finds humanity dwindling away after a zombie outbreak of the fungal variety. Viewers familiar with “zombie ants” will recognize its reference to Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, the real-life fungus that takes control of an ant, grows a sporous stalk from its head, and forces the ant to behave in ways that benefit the continuation of the fungus. In the film, that fungus has mutated and turned humans into a race of hungries that own the world, aside from a few highly secure military sites.

Researchers trying to find a cure use children like Melanie—a second generation of hungries, who were carried within an infected mother only to, horrifically, eat their way out—because they have the fungus but also have mental capabilities beyond their mindless first generation counterparts. Dr. Caroline Caldwell (Glenn Close) believes the children are not human, merely hosts to the fungus; so does the hardened Sergeant Parks (Paddy Considine), who calls the children “abortions.” More sympathetic is teacher Helen Justineau (Gemma Arterton), who cannot help but see someone like Melanie as a living, breathing personality, not an instinctual eating machine. Even so, one whiff of a human scent and Melanie begins to twitch, and her fungus will mindlessly compel her to eat human flesh. (Among the film’s most inspired ideas are the tubes of “blocker” humans use to hide themselves from the hungries’ sharp olfactory sense.)

Inevitably, fast-moving hungries overrun the human compound, sending Caldwell, Parks, Justineau, Melanie, and another soldier (Fisayo Akinade) on a desperate cross-country expedition. To be sure, the film’s second act settles into a familiar rhythm for the zombie genre, where the survivors must travel the perilous road, facing several tense and scary situations. We learn that hungries will rest standing up in a catatonic state, but they awake from a sound or smell. Because the survivors block their sent, they can silently maneuver through a crowd of hungries until, unavoidably, someone makes a peep. Meanwhile, Melanie remains handcuffed with a clear Hannibal Lecter mask strapped to her face, an image the viewer never become accustomed to seeing on a child.

Inevitably, fast-moving hungries overrun the human compound, sending Caldwell, Parks, Justineau, Melanie, and another soldier (Fisayo Akinade) on a desperate cross-country expedition. To be sure, the film’s second act settles into a familiar rhythm for the zombie genre, where the survivors must travel the perilous road, facing several tense and scary situations. We learn that hungries will rest standing up in a catatonic state, but they awake from a sound or smell. Because the survivors block their sent, they can silently maneuver through a crowd of hungries until, unavoidably, someone makes a peep. Meanwhile, Melanie remains handcuffed with a clear Hannibal Lecter mask strapped to her face, an image the viewer never become accustomed to seeing on a child.

The group dynamic among the troupe of characters bears similarities to material like The Walking Dead or the double-feature of 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later (which really needs a sequel). Fortunately, the actors are compelling enough to distinguish themselves. Nanua, in her first screen performance, remains pleasant and natural, yet her humanity also gives way to convincing displays of animal violence. Arterton is excellent in another protective mother role, similar to her jealously parental vampire in Byzantium, while both Close and Considine capture layers of cold logic and reticent humanity. A pack of feral children show up in the film’s third act, and the performances occasionally seem silly, in the same way the post-apocalyptic kids in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome did.

Scottish director McCarthy has helmed episodes from some of U.K. television’s best shows, including Sherlock, Peaky Blinders, Ripper Street, and Dr. Who. And while the film’s low budget becomes apparent in CGI shots that explore the scope of devastation, the director and his cinematographer Simon Dennis deliver a composed presentation and a convincing depiction of post-apocalyptic landscapes. The film’s intentional pacing does much to support our investment in these characters, as does the hypnotic score by Cristobal Tapia de Veer, which hums along with electronic sounds and vocals that recall Radiohead’s album Kid A. Overall, McCarthy’s treatment makes the reported $5 million budget look like ten times that. He delivers a thoughtful entry into a genre that often feels like it has overstayed its welcome; but with this and last year’s Train to Busan, there are clearly some compelling stories left to tell.

Gamers who played The Last of Us may approach with suspicion another story about a journey across a fungus-infected zombified wasteland, in which rugged human characters escort a young girl with a potential cure. But aside from some basic similarities, The Girl with All the Gifts contains a decidedly less humanistic fatalism. Most innovative is the material’s acceptance that humanity doesn’t inherently deserve to continue; rather, Nature chooses which species survive. And if humanity is to be replaced by something else, then so be it. Nature’s progression does not represent a tragedy, just a naturally occurring evolution. To call such a resolution bittersweet would be an understatement, but it’s a sensible conclusion when the human ego is set aside in favor of equilibrium in the biosphere.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review