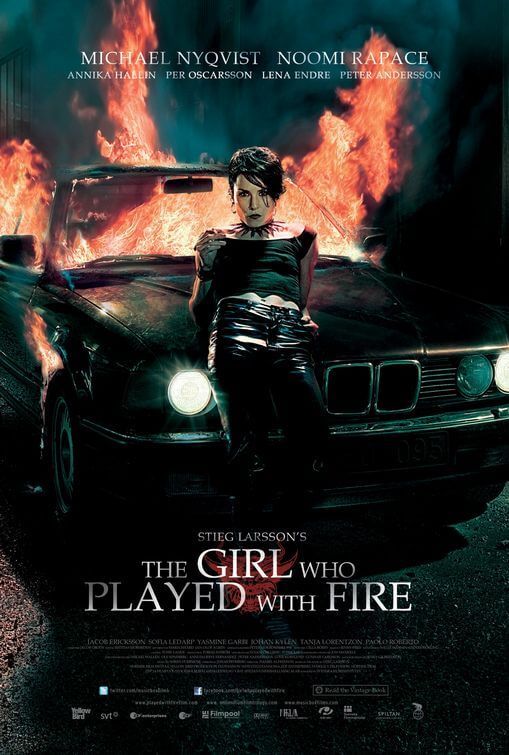

The Girl Who Played with Fire

By Brian Eggert |

In a curious trend, impressive international book sales have made Steig Larsson’s “Millennium Trilogy” a pop-culture phenomenon, suggesting that today’s readers have an affinity for trite mystery, themes of rape, and prose in which the author gives consumer reports on computer technology. The Swedish film adaptations from 2009 have been imported by Music Box Films, earning minor U.S. distribution on the art house circuit; but their popularity has struggled, probably from the announcement that David Fincher (Se7en, The Social Network) plans to make English-language versions for Hollywood. Indeed, if you haven’t seen the Swedish films, this critic’s recommendation is that you wait and experience the story for the first time through Fincher’s eyes. It can only be better.

Still, appraisals of the Swedish versions among the majority of critics are favorable, yet strange given the films’ consistent paradoxical sexuality and the substandard presentation of their mysteries. Take The Girl Who Played with Fire, the second in the trilogy. Director Daniel Alfredson jumps between points of view, among them his two leading protagonists, while other perspectives are indecipherable, and thus muddles any hope for a consistent tone. In turn, the films have been received as both feminist and misogynist by various critics; such a split does not occur because of sound storytelling. This is unfortunate because the basics of the story are not grossly feminist or misogynist, per se, just handled in such a way that twists any interpretation into a confused one.

Larsson’s mystery formula becomes apparent within the first half of The Girl Who Played with Fire, enough so that viewers familiar with the first film, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, will easily predict how the sequel ends, even if the specific culprits can’t be guessed by name. The story begins with more research and hacking montages. There’s more fetishized sex. Another conspiracy involves even more sex crimes among the power classes. The protagonist, troubled goth hacker Lisbeth Salander (Noomi Rapace), once again forms an association with Millennium magazine editor-turned-lover, Mikael Blomkvist (Michael Nyqvist), to solve the rash of crimes. Witnesses die. We learn more about Lisbeth’s sordid past. And in the end, yet again, the villain explains everything before his inevitable failed attempt to kill Lisbeth.

The specifics: A new freelance writer for Blomkvist’s magazine has uncovered a sex trafficking ring among police authorities. Blomkvist and his staff plan to expose those involved, but the evildoers have schemes of their own. When they get wise to the story breaking, they murder the freelance writer and his girlfriend, making it look like Lisbeth committed the crime. These people, you see, are also involved with the seedy lawyer that raped Lisbeth in the first film; that he was eventually blackmailed by Lisbeth is a problem, so he’s murdered too. And so, Lisbeth becomes Public Enemy No. 1, framed for a triple murder. She reaches out to Blomkvist for help, who uses his reporter powers to dig deeper than any detective could. What he uncovers is a conspiracy linked directly to Lisbeth’s past, her alleged insanity, and likely the reason she internalizes her feelings by wearing lots of dark makeup, facial piercings, and spiked collars. This leads to a confrontation with James Bond-esque villains: a man of incredible power who is crippled physically but protected by another man—a massive, blond cartoonish brute who feels no pain.

Perplexing is how this series has handled sexuality. Certainly, in the first film, the off-putting juxtaposition of Lisbeth’s sexual conquests against her graphic rape scene left the viewer in a state of sexual shock and confusion. Here, Lisbeth’s trauma-induced passion for punishing men who abuse women remains a noble aim. But the film hardly sympathizes with her, fuelling the justifiable criticism that Larsson’s trilogy, particularly on film, confuses any hope of bringing awareness to sexism—Larsson’s admitted aim. Instead of telling the story from Lisbeth’s point of view, she is an outsider to her own tale. The filmmakers regard her sex life with gawking, scopophiliac eyes. The film tells us how awful it was that she was raped, or that girls are being trafficked by men in high places, but it treats Lisbeth’s sexuality with a fetishist approach, shooting her love scenes like softcore porn. In a scene where Lisbeth beds a casual female lover, the camera captures the juiciest angles possible in an attempt to entice the viewer. There’s no purpose to this scene, other than the filmmakers’ decision that ‘we need a sex scene here’. It turns Lisbeth into a sexual object for a moment contrary to the rest of the picture. Furthermore, given the number of sex crimes present in this film and its predecessor, it’s doubtful that any viewer has the ability to be turned on by a token sex scene.

Several cold and meaningless moments like this exist in the film and not all of them are sex scenes. Where the screen should be radiating emotion or thrills, Alfredson’s blank approach suggests that he and screenwriter Jonas Frykberg were more concerned about remaining faithful to the book than truly adapting its content to film. Readers of Larsson’s trilogy will find this book’s finer points carried over with impressive detail, though unseasoned for mass consumption. There’s a car chase sequence that peters out before it begins. And there’s a fight scene between a boxer and the blond brute (which even includes a sudden slow-mo knee-to-the-head, complete with laughable reverb on the boxer’s battle cry). Along with the obligatory sex scene mentioned above, these cliché thriller moments show no attempt by Alfredson to involve the viewer. No rousing music. No inventive camerawork.

Perhaps Alfredson sought to make The Girl Who Played with Fire an atypical yarn, pointedly non-Hollywood, and this is why such moments diverge from what we’re used to. It may also be that Swedish thrillers shouldn’t be compared to Hollywood thrillers. But audiences familiar with The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, a capable if troubled mystery, will notice a sharp decline in the quality of storytelling here. And since it’s Larsson’s text that contains the film’s silly clichés and laughable characterizations, Alfredson can only take so much of the blame. Somewhere in the material is a strong story that in the right hands will make a good movie. Those hands do not belong to Daniel Alfredson; maybe they belong to David Fincher.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review