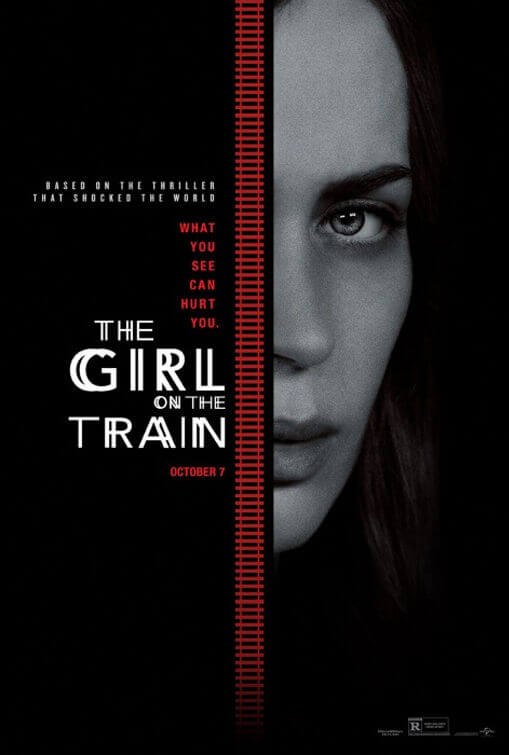

The Girl on the Train

By Brian Eggert |

Emily Blunt’s performance may be the sole reason to seek out The Girl on the Train, a big-screen adaptation of Paula Hawkins’ novel from 2015. Blunt plays an alcoholic somehow involved in a murder case involving scopophilia, various infidelities, and domestic violence. Suburban discontent and a rampant desire for childbearing also have a significant thematic presence in this predictable whodunit, which smacks of Adrian Lyne’s work such as Fatal Attraction and Unfaithful. An overriding lack of dimensionality presides over the entire, rather drab film, as one-note characters behave in ways that propel the story but don’t necessarily feel natural, and certainly not believable. Apart from the film’s acting, fans of the source material should ignore the adaptation and preserve their imagination’s picture of Hawkins’ novel.

The scenario combines Hitchcock with melodrama worthy of daytime television. Screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson attempts to preserve the book’s structural arrangement, but the chapters, announced by white-on-black titles, jump around in way more suitable for literature than for film. Rachel (Blunt) rides to and from Manhattan each day, looking from her train window into the comfortable backyards and windows of luxurious Ardsley-on-Hudson suburban homes. There, she sees her former abode, where her now-ex-husband Tom (Justin Theroux) lives with his new wife, Anna (Rebecca Ferguson), and their new child. For reasons that aren’t exactly clear, Rachel has developed a voyeuristic obsession with the couple two doors down, where Tom’s restless nanny Megan (Haley Bennet) lives with her husband Scott (Luke Evans).

Peered only through the train window, Rachel idealizes Megan and Scott, placing their apparent love on a pedestal. But after she spies Megan kissing another man (Édgar Ramírez), she reaches a personal low on a much-revisited drunken evening—the events of which Rachel cannot remember. When she comes to, she finds a wound on her head, bruises on her back, and vague impressions of what occurred the night before that disturb her—even more so when she learns Megan has gone missing. Could Rachel have killed Megan? That becomes less likely once the film spends time with the other ill-behaved characters, who are written as singularly driven: Rachel exists in a haze of booze; Megan’s damaged past leaves her unsettled; Anna’s primary drive is motherhood and the difficulty with which she handles that task. As for the husbands, Scott just wants a baby and Tom plays a nice guy routine.

Because most of the story is told through the eyes and occasionally misremembered recollections of a drunk, director Tate Taylor (The Help) and his cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen visualize Rachel’s disorientation in distracting, repetitive ways. A viewer can only endure so many fuzzy, unstable, slow-motion shots meant to evoke Rachel’s blurred vision. For whatever reason, Taylor doesn’t trust his film’s strongest component—Blunt’s performance—to stand for itself. Behind her character’s blotched appearance, glassy eyes, and ever-smeared makeup, Blunt presents a (justifiably) wounded protagonist the audience is meant to doubt for far too long. Instead of allowing Blunt’s performance to command the story, the filmmakers rely on a distracting formal presentation.

The sympathy we have for Blunt’s character hardly makes up for her aimlessness for most of the story; only after the climax does she finally discover some purpose. Blunt puts more into the performance than the screenplay allows. Many of the supporting players feel wasted too. Talented actors such as Ramirez and Evans appear as red herrings, nothing more. (Also, Ramirez distractingly plays a Middle Eastern character with a Spanish accent and dialogue, and his character conspicuously disappears once the plot has no use for him.) Allison Janney stars in an underdeveloped role as a hardened detective investigating Rachel and various other suspects. Janney normally plays goofy or eccentric characters, but she’s doing fine work with her otherwise abbreviated screen time. Likewise condensed is the appearance of Lisa Kudrow as an acquaintance from Rachel’s past.

Instead of exploring these characters with meaningful complexity, Taylor’s film is all surfaces: steamy, exploitative love scenes; distracting bookend narration; talented actors who lend their familiar faces to thankless roles; and flashy editing to suggest Rachel’s fractured memory. The cool, detached quality to The Girl on the Train’s color palette and characters cannot help but bring to mind another Girl-titled adaptation, Gone Girl from 2014. But everything that is laughable and absurd about Taylor’s film somehow found a thrilling seriousness in David Fincher’s. Had the filmmakers treated the material as more than just another Hollywood based-on-a-best-seller, and more than a plot, they could have mined the depths of these characters and created something memorable. Alas, The Girl on the Train is easy to forget.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review