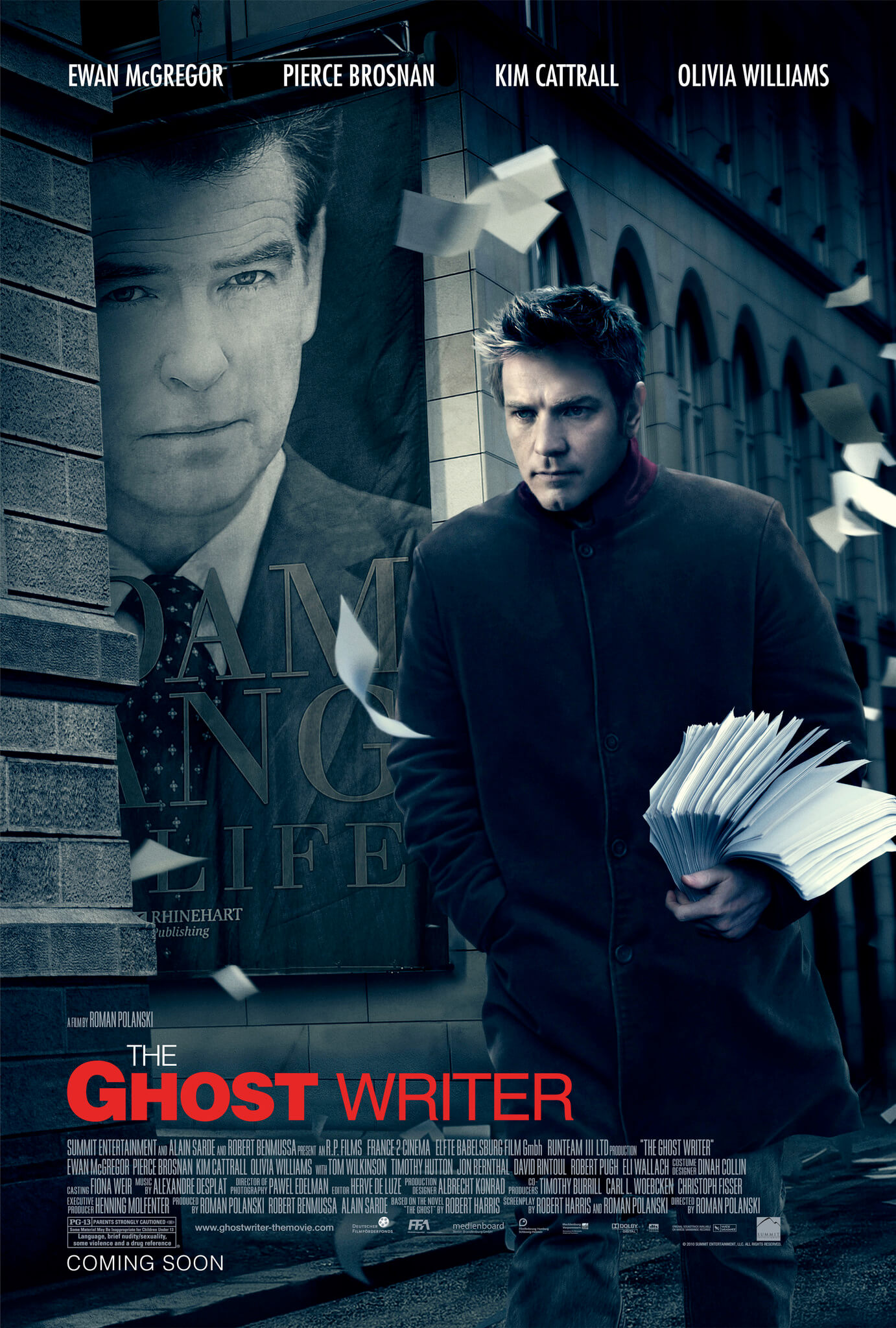

The Ghost Writer

By Brian Eggert |

There’s a scene in Roman Polanski’s The Ghost Writer where former British Prime Minister Adam Lang, played by Pierce Brosnan, has just received some troubling news about being accused of war crimes. Lang is on his cell outside, shouting and swearing at the person on the other end. Our hero, Lang’s nondescript Ghost Writer, watches the call progress through the window. The tension is extremely high and it’s the first time the audience sees Lang as perhaps a dangerous person. Meanwhile, in the frame just behind Lang is a house attendant desperately trying to sweep up leaves and sticks in a violent coastal wind. Every time the wheel barrel fills up, the wind blows its contents away. The audience forgets about Lang’s life-and-death call for a moment to notice this funny, unimportant man struggling to do his remedial job.

Comedy and fear almost never work well together in a thriller, except where Alfred Hitchcock and Roman Polanski are concerned. That’s why they’re masters who time and again find new ways to entertain us using the same old stories. Polanski’s film is an expert thriller, not-so-plain and not-so-simple. The film is smart and comical and gripping all at once. It simultaneously employs the usual tricks of the thriller genre while defying them with a wry sense of wit about how the story is told. There are no guns or explosions, there’s one very ambiguous chase sequence, and the roots of the film are just suspicion and fear and suspense. A sense of danger radiates from the screen and it’s incredibly involving. That it was made by an infamous director should make no difference to you, unless it drives you to see the film. Don’t let the questionable shenanigans of one man prevent you from seeing one of the year’s best films.

Ewan McGregor plays a ghost writer of memoirs; when hired he writes the life story of his client for a fee and allows them to take the credit. And given his trade, he bears the risk of having no identity of his own. And yet, in one of his best performances, McGregor makes the character a rather pleasant Hitchcockian everyman, one with no name or past in the film other than his position. He’s commissioned by the staff of Brosnan’s Lang, a Tony Blair-esque figure both charming and diabolical, to complete a much-anticipated autobiography in a matter of weeks. The Ghost Writer, as he’s known, is flown out to an island off the coast of New England to complete the text. Almost immediately thereafter, it’s announced that Lang is under investigation by a war crimes tribunal for possibly ordering the torture of terrorism suspects. The attention in the press only makes the Ghost Writer’s job juicier and more profitable, but his post suddenly becomes dangerous when he learns he wasn’t the first ghostwriter and the previous one may have been murdered.

McGregor’s character is confined to Lang’s island home to complete the job. He’s not allowed to remove the manuscript from the premises, and Lang’s personal staff, lead by his assistant-cum-mistress (Kim Cattrall), always seems to be around the corner. Polanski creates a claustrophobic environment where there’s almost no safety, giving his audience the feeling that nothing is right, and that everyone working for Lang has a sinister agenda. As the Ghost Writer digs into his subject’s past, he uncovers more and more secrets, all very vague but nonetheless present. Polanski’s supporting actors are experts at giving the story an ominous feeling, particularly when McGregor’s writer meets a character played by Tom Wilkinson (from Batman Begins, Michael Clayton). Dialogue dominates the film’s most spine-tingling encounters—but what magnificent dialogue, adapted for the screenplay by Robert Harris from his novel. Everything is evasive and indirect, and Polanski forces us to try to focus and create a clear image of this intriguing mystery.

McGregor’s character is confined to Lang’s island home to complete the job. He’s not allowed to remove the manuscript from the premises, and Lang’s personal staff, lead by his assistant-cum-mistress (Kim Cattrall), always seems to be around the corner. Polanski creates a claustrophobic environment where there’s almost no safety, giving his audience the feeling that nothing is right, and that everyone working for Lang has a sinister agenda. As the Ghost Writer digs into his subject’s past, he uncovers more and more secrets, all very vague but nonetheless present. Polanski’s supporting actors are experts at giving the story an ominous feeling, particularly when McGregor’s writer meets a character played by Tom Wilkinson (from Batman Begins, Michael Clayton). Dialogue dominates the film’s most spine-tingling encounters—but what magnificent dialogue, adapted for the screenplay by Robert Harris from his novel. Everything is evasive and indirect, and Polanski forces us to try to focus and create a clear image of this intriguing mystery.

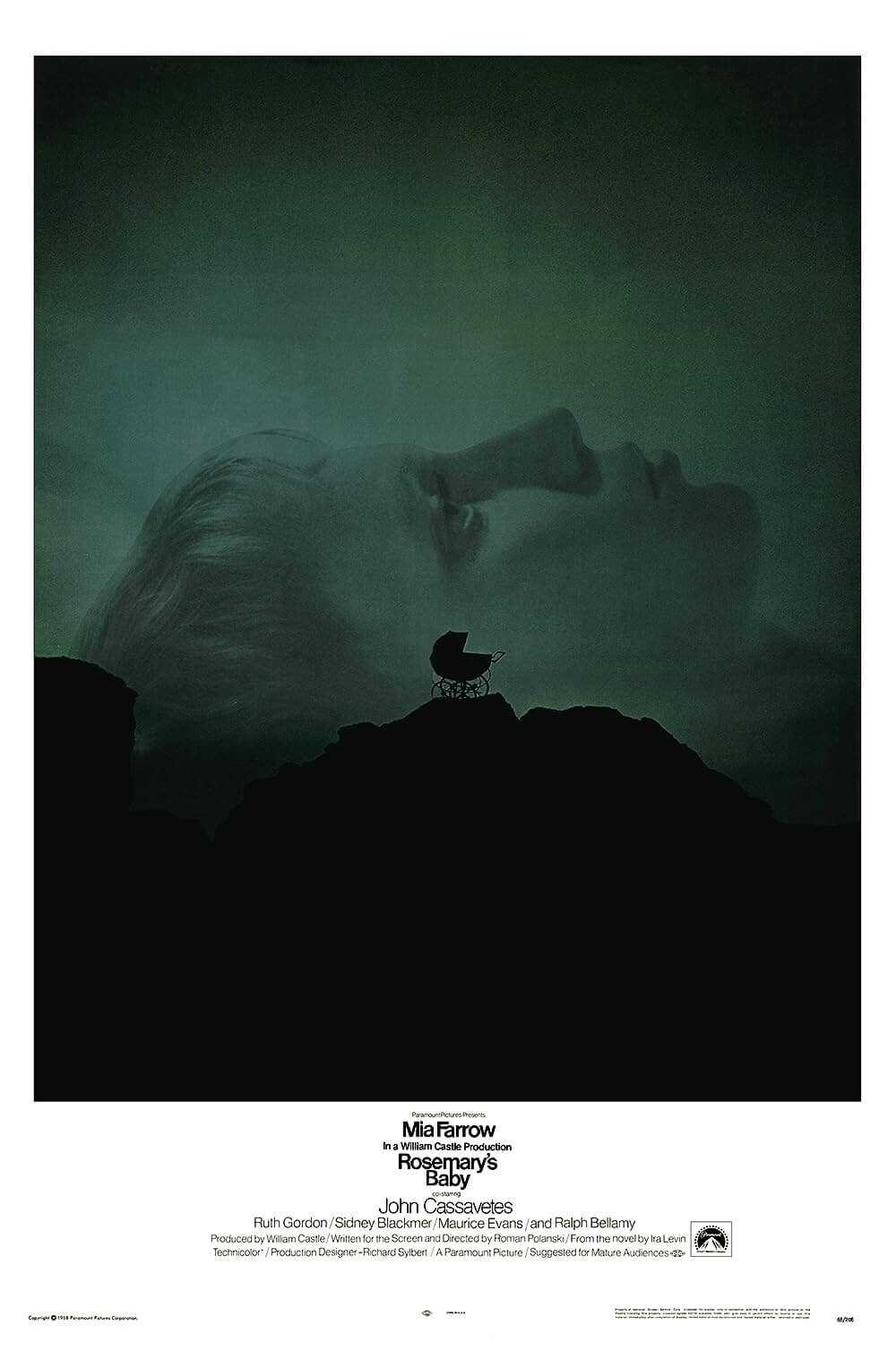

Audiences familiar with Polanski’s thrillers know that his films are all about the often comedic details, and how these details work to enhance the impact of the suspense by forcing the audience to let their guard down. In Rosemary’s Baby, the silliness of the elderly neighbors the Castevets becomes even more twisted when it’s revealed that they’re Satanists. In The Tenant, we laugh one moment at the sudden cross-dressing and obligation to social niceties, then gasp in another moment when there’s a human tooth found in the wall. And certainly, that star Jack Nicholson went through the majority of Chinatown with an awkward bandage on his nose was meant to make the audience laugh, which only intensifies our sympathy for the otherwise serious film noir character.

While working in standard conventions, Polanski usurps the norm with his own flourishes to give his characters life and the scenario edge. He does this wonderfully in The Ghost Writer by admitting to the audience that the characters have obligatory thriller roles that they must follow. But the way Polanski presents these roles gives them their dynamic because he doesn’t try to disguise them. Consider a scene where Lang’s troubled wife (Olivia Williams) comes into the Ghost Writer’s bedroom one night. Lang is away on business and she’s been crying in the rain, so she’s robed and her hair is wet. The writer gets up to get Lang’s wife a towel from the bathroom. He looks in the mirror and says, “Bad idea,” which is just what the audience was thinking. When he returns, she’s naked in his bed to warm up. As if pulled by the conventions of storytelling, the writer casually walks to the bed, drops his robe, and gets in. They lay there for a moment, both naked, knowing what their characters are supposed to do, and then they do it. It had to happen. By the final scene, which is utterly perfect, the audience realizes the entire production is an exercise in the manipulation of conventions, and the joke’s on us.

The film has the potential of housing a substantial political commentary but chooses to be a great thriller instead. There’s a sly parallel between Brosnan’s suave portrayal of Adam Lang and Tony Blair as mentioned above, one that implicates Blair as a puppet to U.S. interests. However, The Ghost Writer isn’t about this otherwise apparent message. Polanski is more interested in the isolation of the setup and the interaction of these characters: The cocky writer, the powerful Prime Minister, the mistress-assistant, the jealous and angry wife, and all of their secrets. It’s all very gripping and engulfs the viewer, and the winding yet dryly humorous music by Alexandre Desplat, who was recently nominated for an Oscar for his work on Fantastic Mr. Fox, underscores Polanski’s intention splendidly.

The film has the potential of housing a substantial political commentary but chooses to be a great thriller instead. There’s a sly parallel between Brosnan’s suave portrayal of Adam Lang and Tony Blair as mentioned above, one that implicates Blair as a puppet to U.S. interests. However, The Ghost Writer isn’t about this otherwise apparent message. Polanski is more interested in the isolation of the setup and the interaction of these characters: The cocky writer, the powerful Prime Minister, the mistress-assistant, the jealous and angry wife, and all of their secrets. It’s all very gripping and engulfs the viewer, and the winding yet dryly humorous music by Alexandre Desplat, who was recently nominated for an Oscar for his work on Fantastic Mr. Fox, underscores Polanski’s intention splendidly.

The director’s personal life has unfortunately affected the film, and not only to the point of driving some self-righteous moviegoers away. First, there’s the curious parallel provided by the plot: a Ghost Writer must complete a crucial project on veritable house arrest while his client fears extradition. Polanski all but completed the final cut of the film before being detained in Switzerland in September 2009 for his outstanding warrant, but he put on the finishing touches via laptop while on house arrest awaiting extradition. How foretelling. The film’s editing and structure don’t suffer at all from his detainment; it looks wonderful. But because the distributors at Summit Entertainment feared Polanski’s reputation would hurt the film’s release, to earn a more audience-friendly PG-13 rating audio looping covers derivations of the word “fuck” and replaces them with “bugger” and “frickin’” and so forth. The result is occasionally and momentarily distracting, though most audiences won’t even notice it. It’s a minor quibble, but a likely result of Polanski’s recent media attention nonetheless.

The Ghost Writer is a subtle and elegant thriller, a work that demonstrates a 76-year-old master who after 50 years of filmmaking remains in full control of his artistic faculty. Polanski had his share of rough spots in the 1980s and ‘90s, but he’s returned with his best film in decades. So forget the director if it’s a problem for you. This is a brilliant, paranoid, anxiety-ridden film free of gimmicks and wrought with suspense, not to mention the blackest of black comedy. It’s an achievement in atmosphere and dread, while it also wields a tight plot and superb performances from its cast. When it’s become increasingly difficult to find anything worthwhile in the genre of late, that Polanski has landed such an intelligent contemporary thriller using classic motifs proves extraordinarily satisfying, and a testament to his status as one of the greatest living directors.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review