The Gentlemen

By Brian Eggert |

There’s a scene late in Guy Ritchie’s The Gentlemen where a seedy private investigator named Fletcher, played by Hugh Grant, pitches a film in Miramax’s London offices. The executive, sitting before a wall of golden awards, sounds pleased with Fletcher’s spiel, a summation of the film we’ve just seen to this point, and he wants a deal. “What you want is a sequel,” Fletcher replies with a smile. Hung somewhat obscured behind Grant is a poster of Ritchie’s The Man from U.N.C.L.E. from 2015, a pleasant but underperforming based-on-a-TV-show spy yarn that deserved a follow-up but will never receive one. Did Ritchie implant this detail as a not-so-subliminal message to audiences that the distributors at Warner Bros. should continue the franchise? Or is Ritchie exposing Hollywood’s current obsession with intellectual property as sustainable revenue? It’s a flourish that comes more than an hour after Fletcher argues for the 35mm glory days and cinema that crackles like a record player. But it’s difficult to reconcile whether Ritchie believes Fletcher’s sentiments, or if he’s used Grant’s slithering, predatory character to represent an outmoded style. Maybe it doesn’t matter. Maybe we just appreciate that, after his plethora of surprising performances in Cloud Atlas (2012), his role as the many-layered husband in Florence Foster Jenkins (2016), and his delightful turn in Paddington 2 (2017) as a self-obsessed actor, Grant has found his calling as a character actor.

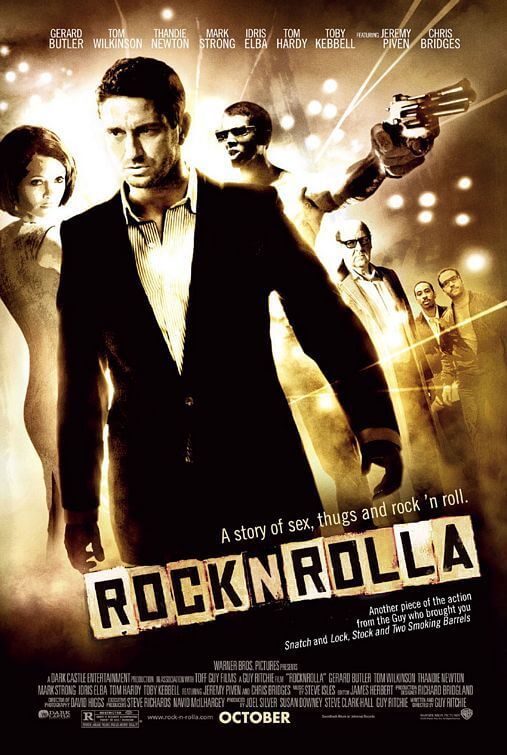

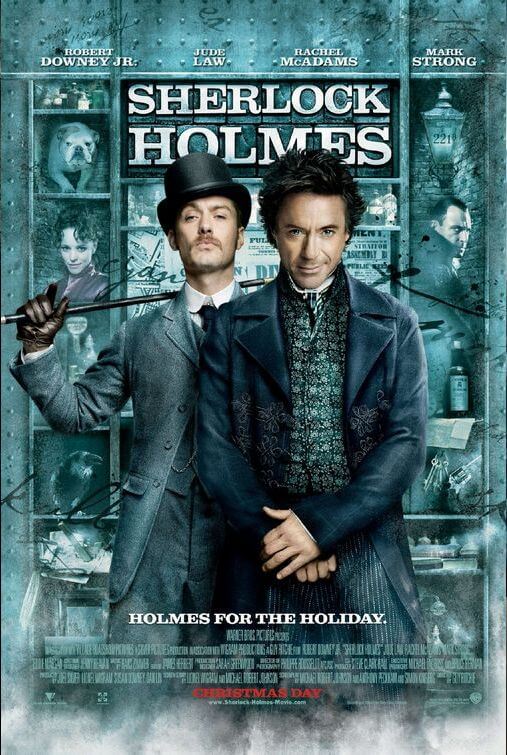

By most accounts, the Cockney-accented, post-Tarantino flavor of Ritchie’s early output has dissolved into an indistinguishable blockbuster aesthetic over the last decade. His arrival with the pulsive energy of Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998) and Snatch (2000) made him hugely popular, giving the British gangster genre a resurgence in UK cinema. He managed to repeat his darkly comic, zigzag-plotted, and juicily worded mode of crime story at least once, with 2008’s RocknRolla, before gradually blotting out his signature with a series of increasingly impersonal tentpoles—Sherlock Holmes (2009) and its sequel look like passion projects next to King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2017) and last year’s live-action Aladdin. By comparison, The Gentlemen has a back-to-basics feel, with its star-studded cast of quirky characters, most of them men distinguished by the single trait Ritchie has written for them. It’s a film about drug kingpins and wannabe hoodlums, tough guys and brash businessmen, heroin junkies and lords of the manor, underwritten roles for women and racial humor in the name of equal-opportunity offenses. Ritchie has returned to subject matter that made him famous, only to discover that some of his methods belong in the past.

Ritchie contains his story within two narrative structural devices, though usually, one is enough. The Gentlemen opens with Matthew McConaughey, playing London’s premier marijuana magnate Mickey Pearson, an American dressed to the nines in a London pub. An Oxford dropout and horticulture whiz, Mickey made his fortune building indoor farms on property owned by the most recent generation of British lords and ladies, who need his payoffs to finance the upkeep on their venerable estates. In the first scene, after ordering a pint and a pickled egg, he sits down and seemingly takes a bullet to the head. Then Ritchie takes us back to the beginning in a loose whodunit style, begging the audience to view every character in his rogues’ gallery as a possible suspect. Since Mickey has quietly planned to sell his empire and retire into middle-age contentment, the culprit could be any number of competitors: Jewish businessman Matthew Berger (Jeremy Strong), another American like Mickey, plans to pay $400 million for Mickey’s organization. But an ambitious Chinese gangster called Dry Eye, played by Henry Golding with all the combustible energy of Joe Pesci in Casino (1995), wants the empire for himself. Meanwhile, Big Dave (Eddie Marsan), the sleazy editor of a local tabloid, has hired Fletcher to keep tabs on Mickey after a personal slight at a posh soiree.

“There’s fuckery afoot,” as one Cockney gangster observes, and the whole sordid mess is retold in flashback by Fletcher, who details the various players and their motivations to Mickey’s bookish consigliere, Raymond (Charlie Hunnam). Fletcher has invited himself into Raymond’s home at night with a blackmail scheme, hoping to get millions for his downright cinematic understanding of the events as they happened—-along with the occasional flirtatious advancement at Raymond, signaling a kind of villainy around the implied gayness. As Fletcher proceeds with “laying the pipe, as they say in the film world,” The Gentlemen flashes back to the events as Grant’s unreliable narrator, an apparent stand-in for Ritchie himself, imagines they happened. Having written a screenplay called Bush, he layers the tale with self-aware cinematic imagery “in full 2.35:1 scope,” and Alan Stewart’s lensing adjusts the frame accordingly. And while Fletcher’s film-within-a-film affords us the pleasure of listening to a superb Grant comment on each scene, Ritchie gives up on the device in the last third, and the story loses its momentum. This is in part due to the remaining murder mystery device, and the fact that we never really believed Ritchie would kill his film’s biggest star, even if it would have been a bolder choice.

“There’s fuckery afoot,” as one Cockney gangster observes, and the whole sordid mess is retold in flashback by Fletcher, who details the various players and their motivations to Mickey’s bookish consigliere, Raymond (Charlie Hunnam). Fletcher has invited himself into Raymond’s home at night with a blackmail scheme, hoping to get millions for his downright cinematic understanding of the events as they happened—-along with the occasional flirtatious advancement at Raymond, signaling a kind of villainy around the implied gayness. As Fletcher proceeds with “laying the pipe, as they say in the film world,” The Gentlemen flashes back to the events as Grant’s unreliable narrator, an apparent stand-in for Ritchie himself, imagines they happened. Having written a screenplay called Bush, he layers the tale with self-aware cinematic imagery “in full 2.35:1 scope,” and Alan Stewart’s lensing adjusts the frame accordingly. And while Fletcher’s film-within-a-film affords us the pleasure of listening to a superb Grant comment on each scene, Ritchie gives up on the device in the last third, and the story loses its momentum. This is in part due to the remaining murder mystery device, and the fact that we never really believed Ritchie would kill his film’s biggest star, even if it would have been a bolder choice.

Though Ritchie’s crime films usually entail small-time crooks getting in over their heads with intimidating and deadly bosses, he approaches The Gentlemen from the other end. It’s a tougher sell, rooting for someone on top, whereas the desperate maneuvers of those on the bottom have an inherent drama to them. Mickey spends more time waxing philosophical about his station (“there’s only one rule in this jungle: when the lion’s hungry, he eats” or “it’s not enough to act like the king, you must be the king”) than he does earning the audience’s favor. More interesting, as always, are Ritchie’s supporting players. Colin Farrell plays Coach, a boxing trainer whose posse of students, among them, British rapper Bugzy Malone, create music videos out of their fights. Likewise, Mickey’s wife Rosalind (Michelle Dockery) could have used some additional runtime. She’s usually on Mickey’s arm, but on the side, she runs an all-women mechanic shop as a legitimate business. Her character may be interested in showcasing women, but Ritchie uses Rosalind as a device—she’s “the wife” who, hardened though she may be, still needs to be rescued from rape in a climactic scene.

About midway into The Gentlemen, the accumulation of its slight homophobia, limited roles for women, and casual racism defended as all-in-good-fun begin to distract. To be sure, there’s would-be comic repartee about Berger, a backdealing Jew and gay stereotype, who is accompanied by two bodyguards he calls the “Mossad Crabs.” Christopher Benstead’s score borders on an “Oriental riff” during scenes with Chinese gangsters, while Goulding is referred to as the Chinese James Bond with a “rice-sense to kill.” At one point, Coach must explain to a black student that one of his peers made a racist joke out of love. And the generous use of “cunt” in various situations, with multiple meanings and nuances, is bound to offend mostly U.S. viewers who unfortunately haven’t warmed up to the pliable word. Of course, Ritchie’s screenplay openly dismisses such un-PC material as a trap for the hyper-sensitive, preferring to embrace the offensive and profane as part of a style derived from grittier British crime films such as Get Carter (1971), Scum (1979), and The Long Good Friday (1980). You get the impression that, after working with studios like Warner Bros. and Disney for the last decade, Ritchie couldn’t wait to unleash every foul impulse in one film.

Whether you consider Ritchie’s approach old-fashioned (as in paying homage to an era of blistering British crime cinema), self-referential (as in trying to recapture his own style from the turn of the century), or some combination of both, The Gentlemen seems to ruminate on the past and present in unclear ways. Even so, the film contains memorable moments that make the messy and twisting plot worth trying to figure out: Farrell’s introduction as an honorable fighter in an embarrassing tracksuit shows him hilariously confronting some rowdy teens. Hunnam’s role might seem to be Mickey’s accountant until it’s revealed what he’s carrying underneath his coat. And it’s refreshing to see Goulding avoid another typecast role as the rom-com hunk. But it’s Grant who steals the show, lending the film a character at once despicable, charming, funny, and complicated. To whatever degree Fletcher reflects some aspect of Ritchie remains uncertain and, frankly, less interesting than the pleasure of watching Grant do his thing. The Gentlemen may contain some questionable material at times, but it’s too entertaining in its richness of character to ignore.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review