The French Dispatch

By Brian Eggert |

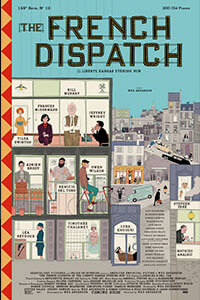

The French Dispatch is Wes Anderson’s billet-doux to The New Yorker magazine. His tenth feature is also his latest in a long line of odes to French cinema. Like any of his other films, it’s an imaginative, meticulously designed, and intentionally constructed objet d’art. It’s a pretty thing that one stands back from and reflects, “Isn’t that a pretty thing.” Every moment contains boundless details that have been labored over by Anderson and his team of artists, designers, and craftspeople, and much of their work points to particular writers or movies. The effort that goes into each frame is staggering. Adopting the structure of a magazine, the film is composed of several articles or stories. It plays like an anthology, weaving characters galore and nimble plotting together into an intricate and deliberate pattern. Anderson shoots in his usual style that makes everything look contained in the frame, like a beautiful stage made from miniatures, moveable walls, and fabricated spaces erected with fabulist flair. The French Dispatch would doubtless win the blue ribbon prize in a competition for the best living diorama. But it’s deficient of a particular element, some might say an essential requirement, of narrative cinema: emotion.

Afterward, I thought to myself, “What an impressive piece of filmmaking that made me feel next to nothing.” When it was over, I didn’t feel a strong desire to hug my wife, repair a damaged relationship with a friend or family member, or even squeeze my dog (as one often does after Anderson films). Though not without the occasional chuckle or tender feeling, the material does not challenge the viewer, and one feels impressed only by the amount of work that went into its making. In some ways, The French Dispatch might reveal Anderson at his most fastidious and uncurbed. He leans into his own worst tendencies here, concerning himself primarily with all those fascinating details that merely supply the accents and aesthetic quirkiness to his earlier films. Of course, it’s remarkable that Anderson has remained visually consistent for so long. His directorial signatures have been thoroughly examined and studied, parodied and copied, to the extent that they have become dependable and predictable. However, his latest shows that his lack of growth as an artist has become troublesome. He so loses himself in craft, technique, and artifice—and enough references to Tati, Godard, and Truffaut to please even casual Francophiles—that he forgets to give the story any heart.

Still, his ensemble cast and central conceit hold countless promises, and Anderson’s treatment of visual and aural stimuli keeps our eyes and ears delighted. Even if the viewer has never read The New Yorker and wouldn’t know Mavis Gallant from Mavis Leno, Anderson’s face-value approach, which has increasingly become his defining mode over the years, proves appealing in its accessibility. It’s impossible to absorb every nod to great writers or classic French movies on a single sitting, but The French Dispatch’s denotative quality does not preclude enjoyment. Still, its references remain entrenched in a surface-level saturation of detail that will tickle those capable of identifying them—they might also be the whole point of the film. Anderson’s screenplay gives us some flavor of another sophisticated world, seen through the eyes and words of writers. A magazine published out of rural Kansas and overseen by editor Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray)—based on The New Yorker’s longtime editor Harold Ross—the film’s titular publication is coming to an end. We see the final issue unfold over four stories, followed by the obituary of its editor, who leaves strict orders to halt publication in the event of his passing.

Still, his ensemble cast and central conceit hold countless promises, and Anderson’s treatment of visual and aural stimuli keeps our eyes and ears delighted. Even if the viewer has never read The New Yorker and wouldn’t know Mavis Gallant from Mavis Leno, Anderson’s face-value approach, which has increasingly become his defining mode over the years, proves appealing in its accessibility. It’s impossible to absorb every nod to great writers or classic French movies on a single sitting, but The French Dispatch’s denotative quality does not preclude enjoyment. Still, its references remain entrenched in a surface-level saturation of detail that will tickle those capable of identifying them—they might also be the whole point of the film. Anderson’s screenplay gives us some flavor of another sophisticated world, seen through the eyes and words of writers. A magazine published out of rural Kansas and overseen by editor Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray)—based on The New Yorker’s longtime editor Harold Ross—the film’s titular publication is coming to an end. We see the final issue unfold over four stories, followed by the obituary of its editor, who leaves strict orders to halt publication in the event of his passing.

In traditional anthology fashion, the top-level story centered on Howitzer’s editorial office frames the other segments. Howitzer meets with the issue’s various writers, whom he fiercely protects and respects. “Make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose,” he tells them. Each of them writes an article set in the town of Ennui-sur-Blasé—a comically stereotypical French name, to be sure, which captures the New Wave spirit that Anderson so adores. Before the main features, Owen Wilson appears as a travel writer who turns in a short piece on the flavor and mood of the town. Then comes the first long segment: Tilda Swinton’s character offers a story about a convicted killer (Benicio del Toro) who creates painterly masterworks of modern art—though oddly, we see her character relay the story in a public lecture and not Howitzer’s reading of it. The second story follows Frances McDormand’s journalist getting personally involved in the 1968 student riots in France, with plenty of teargas, sadness, and young love to follow. The final report, and the best of them—this one told to a TV talk show host—involves a food critic (Jeffrey Wright) on assignment to sample some French police cuisine, only to become embroiled in a kidnapping and ransom yarn.

Anderson fashions each story with an embarrassment of cinematic riches. Look at the cast of recognizable faces and names, far too many to list in this review. Actors like Saoirse Ronan, Christoph Waltz, and Elisabeth Moss have roles limited to a line or two. That’s part of the fun, sure, but it’s borderline gluttonous. In a sense, the film captures how any artistic project, be it a feature film or a single issue of a magazine, requires the work of so many supremely talented people that sometimes go unnoticed or underutilized. Accordingly, the staggering cast feels overshadowed by the sheer volume of technical trickery and visual input on display. Anderson uses black-and-white photography, miniatures, various aspect ratios (though mainly the boxy Academy Ratio), stop-motion animation, and scale models to render a fanciful world from his imagination. A few animated sequences recall the cartoon Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin from the 1960s. One sequence on a stage feels like a Max Fischer production. In the final story, Anderson uses a split-screen to show a culinary delicacy on the left; at the same time, the police chief (Mathieu Amalric) details his plan to recover his kidnapped son on the right. Given that English subtitles stylistically translate the French dialogue, compelling the viewer to read them, we can’t possibly appreciate the delicacy and read the exposition. So naturally, our eyes gravitate to the food, and we miss the chief’s plan.

As similarly overloaded scenes like this unfold, the viewer feels like Anderson has sabotaged us. It’s impossible to keep up, requiring either multiple viewings or retreat. Two or three more screenings might do the trick, if The French Dispatch contained the emotional resonance that so many of his films do, thus rewarding a rewatch. However, for all the film’s flashes of greatness, charming ornamentation, whimsical formal choices, saturated nostalgia, and even the occasional inspired performance—despite the crushingly limited screentime reducing every character to a note or two—there are no powerful feelings to be had. Under such conditions, the viewer has nothing to cling to but the production’s details and eccentricities, combined with a few unfortunate tendencies. Take Anderson’s usual function for female characters, limited to love interests or disapproving and stoic figures, often in the form of a mother. Among the film’s dozen or so roles for women, there are exceptions to this rule. But Anderson cannot resist portraying his female leads through the lens of their sexuality, resorting to his usual full-frontal displays of female nudity—even Swinton’s goofy art lecturer appears naked in a random and throwaway gag. It’s all quite typical for Anderson, and it might even be forgivable if the experience led to something more than just a mountain of fascinating surface details.

As similarly overloaded scenes like this unfold, the viewer feels like Anderson has sabotaged us. It’s impossible to keep up, requiring either multiple viewings or retreat. Two or three more screenings might do the trick, if The French Dispatch contained the emotional resonance that so many of his films do, thus rewarding a rewatch. However, for all the film’s flashes of greatness, charming ornamentation, whimsical formal choices, saturated nostalgia, and even the occasional inspired performance—despite the crushingly limited screentime reducing every character to a note or two—there are no powerful feelings to be had. Under such conditions, the viewer has nothing to cling to but the production’s details and eccentricities, combined with a few unfortunate tendencies. Take Anderson’s usual function for female characters, limited to love interests or disapproving and stoic figures, often in the form of a mother. Among the film’s dozen or so roles for women, there are exceptions to this rule. But Anderson cannot resist portraying his female leads through the lens of their sexuality, resorting to his usual full-frontal displays of female nudity—even Swinton’s goofy art lecturer appears naked in a random and throwaway gag. It’s all quite typical for Anderson, and it might even be forgivable if the experience led to something more than just a mountain of fascinating surface details.

I consider myself a Wes Anderson fan, having downright loved every film to his credit until Isle of Dogs (2018), a mildly disappointing work of stop-motion animation—beautifully crafted but more concerned with style than substance. My response to The French Dispatch is similar. Something has changed in his work over these last two films, and it’s tempting to diagnose the problem. My first thought was to blame the screenplay since most of Anderson’s best films involve co-writer credits for Owen Wilson, Noah Baumbach, Jason Schwartzman, or Roman Coppola. The latter two receive “Story by” credit here, along with Hugo Guinness, but the screenplay is all Anderson. The same was true of Isle of Dogs, suggesting that the director may need another voice to inject some much-needed heart into the proceedings. Then again, he was the sole credited screenwriter of The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), arguably his best film to date, so there goes that theory. Maybe Wilson’s melancholy or Baumbach’s preoccupation with dysfunctional families could have enriched the proceedings, but that isn’t very likely given the anthology structure. Whatever the explanation, Anderson has changed somehow as a filmmaker. His obsessions have gotten the better of him and consumed his output. Our eyes remain occupied by frenzied consumption, but when it’s over, the experience doesn’t last. Visually stimulating though it may be, something is missing from The French Dispatch.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review