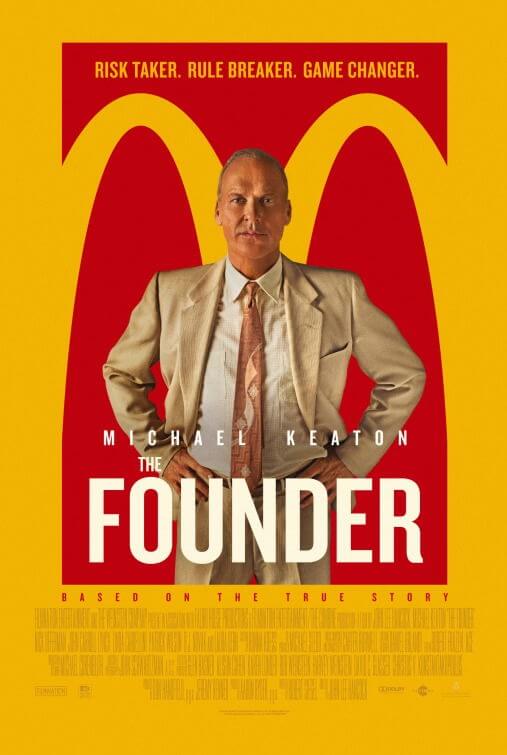

The Founder

By Brian Eggert |

The Founder should come with a warning: Film proves blander than it may appear. In another case of aggravatingly deceptive trailers, following 2016’s Chris Pratt and Jennifer Lawrence starrer Passengers, the advertisements for the biopic of McDonald’s shyster Ray Kroc appear to contain a more engaging film than the one delivered. The first official trailer has been available since April 2016, with the film’s release planned for the following August. After talk of potential awards consideration for Michael Keaton, whose energetic portrayal of Kroc contains all the bravado of his turn in Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), the film shifted dates to a limited release in December, and finally a wide distribution in January. For nearly ten months, prospective viewers have been sold a formally innovative, fast-paced picture in which the fourth-wall-breaking protagonist revels in his duplicitous back dealings.

Of course, trailers are lies meant to draw audiences. And as Passengers demonstrated, the more egregious the advertising lie, the more viewers will reject the film for the disparity. As a critic accustomed to such deception, I should have been better prepared for it and not allowed my expectations to influence my eventual assessment. Nevertheless, dear reader, I am a human being and devoted moviegoer, just like you. And just like you, I am capable of disappointment. Frankly, I wanted to see a better film than the one delivered by director John Lee Hancock. It’s a bland, decidedly straightforward film instead of the lively one advertised. Worse, the film neglects to ask what may seem like obvious questions given the subject matter.

Specifically, the screenplay by Robert Siegel fails to consider the implications of McDonald’s from any other perspective than biographical. Not that this comes as a shocker, given its director. In recent years, Hancock has made several of the most frustratingly one-note films about otherwise complex topics. His Oscar-winner The Blind Side (2009) raised eyebrows by telling the story of underprivileged student-turned-football-player Michael Oher from the perspective of a sassy, well-to-do white woman. Next came Saving Mr. Banks (2013), a fictionalized account of Walt Disney’s attempts to adapt P. L. Travers’s Mary Poppins, except with a fabricated ending that suggests Travers and Disney got along swimmingly (the opposite was true). And so, most of the hard-hitting questions about Ray Kroc and the economic, environmental, and dietary consequences of the McDonald’s empire on American, nay, world culture are simply ignored in The Founder.

The story begins in 1954, as Illinois salesman Ray Kroc (Keaton) peddles milkshake mixers to drive-in restaurants throughout the Midwest, while his wife, Ethel (Laura Dern), remains lonely and bored at home. Kroc soon learns of an order for six mixers from a single San Bernardino burger stand and resolves to visit the owners personally—after all, he can hardly sell a single mixer. Who would ever need so many? When Kroc arrives at the first McDonald’s location, he’s intrigued by the efficiency and innovation before him. Employees function as cogs in a well-oiled machine with many moving parts, each timed to maximum output and profit. Rather than use dishes that must be washed or waste money on roller-skated servers, the food is packaged in paper and there’s an order window. Before McDonald’s, the notion of “fast food” simply did not exist. (Note: Kroc wasn’t the only person to visit the McDonalds’ operation. Keith J. Kramer and Matthew Burns also visited them and borrowed their model to launch Burger King, a detail The Founder overlooks.)

After some initial and justifiable hesitation, brothers Mac (John Carroll Lynch) and Dick (Nick Offerman)—the former being the restaurant’s friendly face, the latter being its brainchild—strike a deal with Kroc. As a franchise manager, Kroc goes around the country and establishes several locations, while also overseeing quality control. He eventually learns he shouldn’t be seeking out already-privileged investors; rather, he should seek out the American everyman. His pitch to Mac and Dick outlines his intention to associate the McDonald’s “golden arches” with the crosses on every church and the American flag on every courthouse across the country, in essence creating a holy trinity of American values. Kroc’s vision includes providing a place where the American family eats an affordable meal in minutes, while the American investor purchases the American Dream in the form of a franchise. (It should be noted that both Kroc and Hancock define your average American family and employee at McDonald’s in this era as almost exclusively white.)

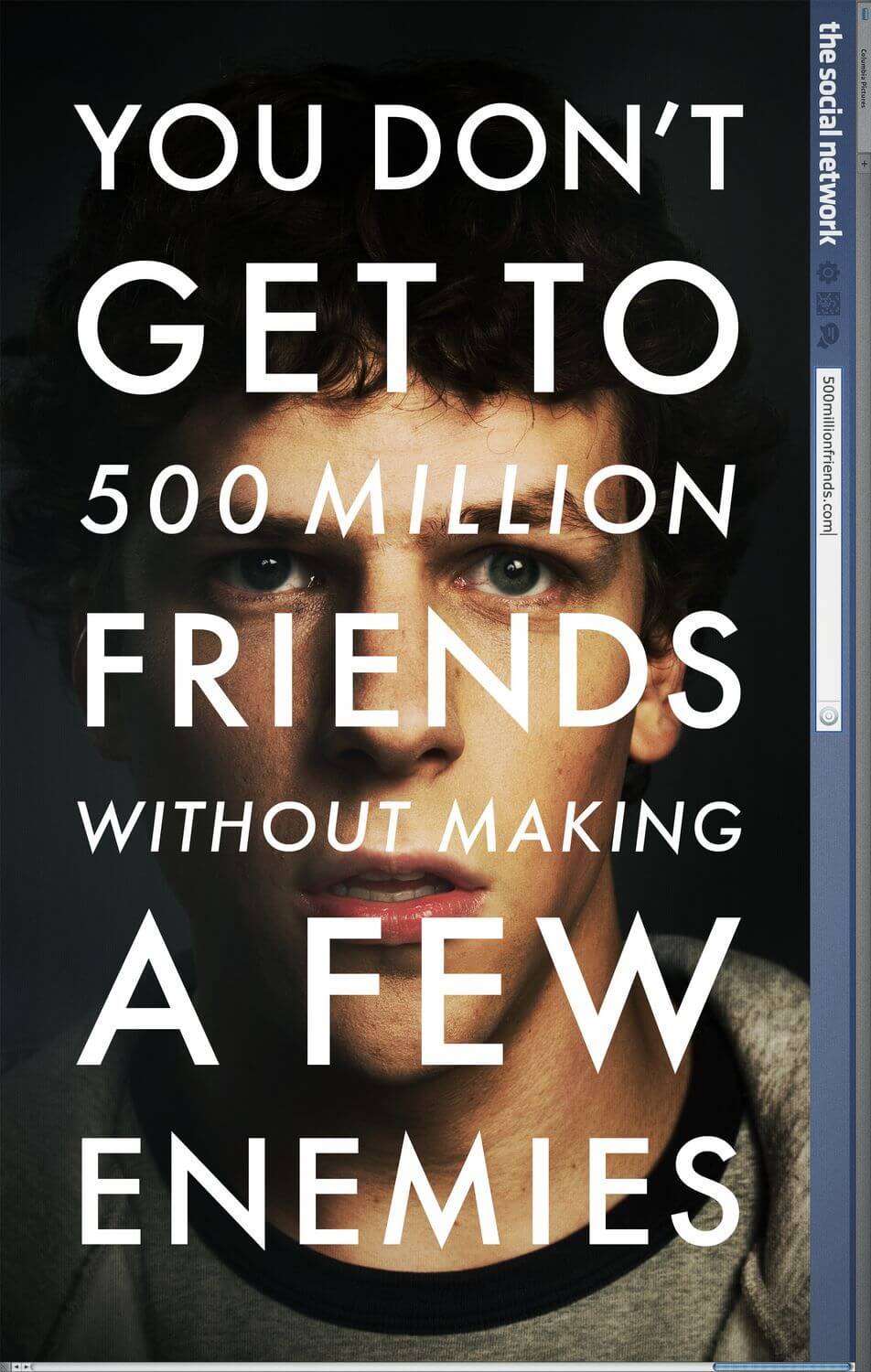

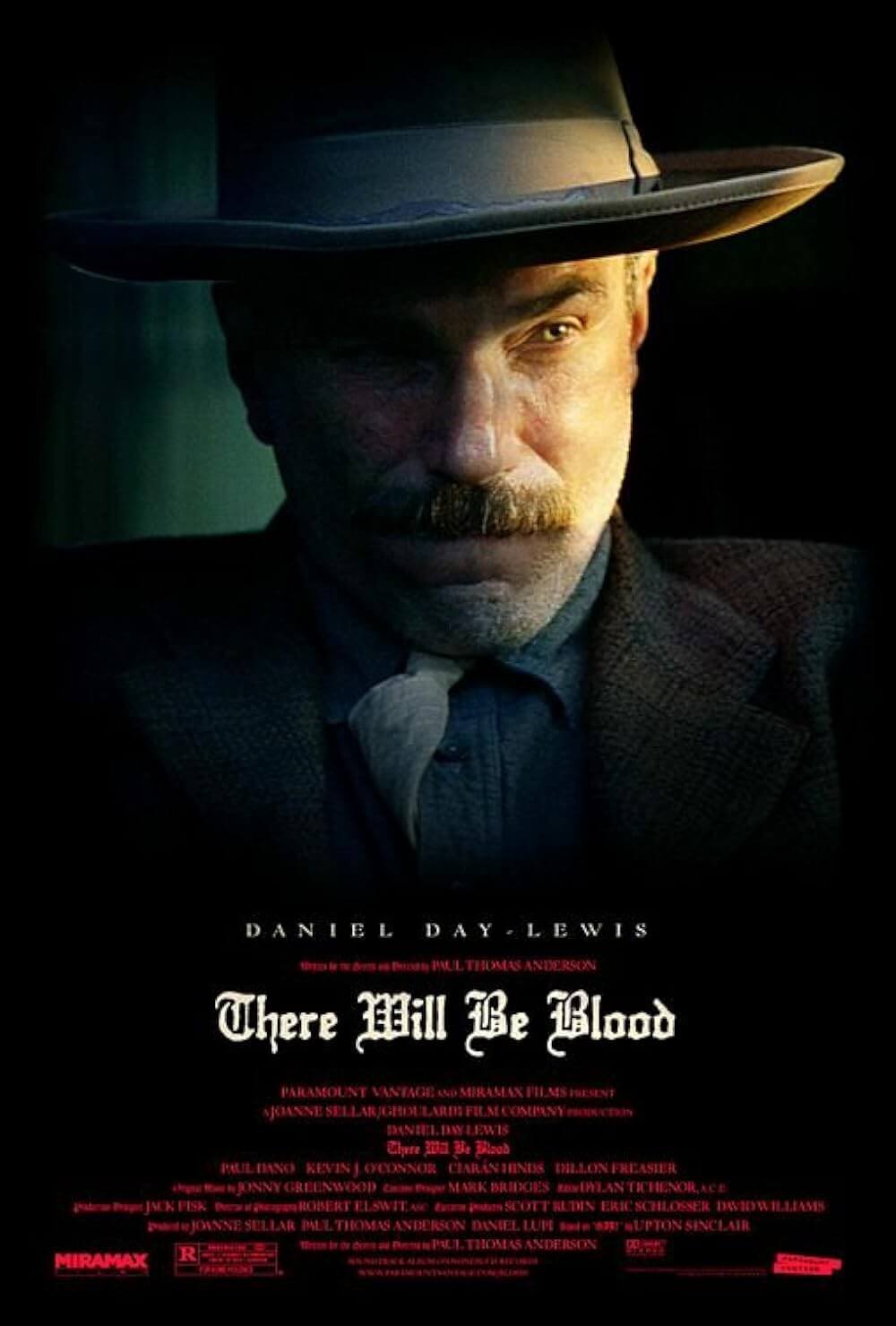

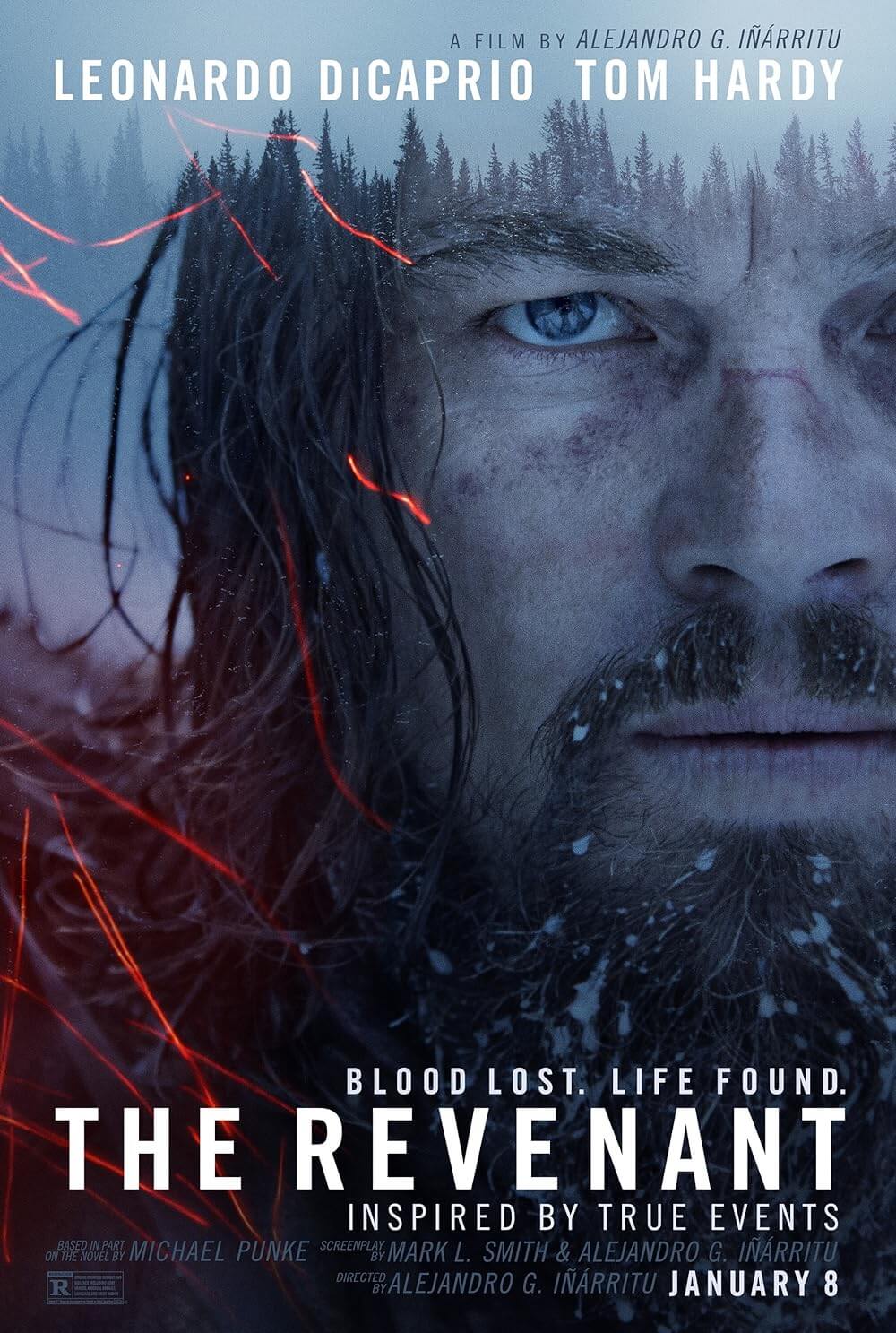

The drama plays out in a way not dissimilar from David Fincher’s The Social Network (2011), in which the innovator steals an idea from the inventor for himself. Kroc learns from his future business partner (B.J. Novak) that he shouldn’t be relying on a percentage of each franchise for his income; he should be buying the land on which the franchise locations are built. After weaseling his way into a fortune by betraying his partners, Kroc’s arrogance and opportunism transform him into a sunnier version of Daniel Plainview from Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007). Although, Hancock seems to admire Kroc’s ambition and persistence, as well as the resulting legacy, instead of despising the obvious ethical downfalls. The film certainly does not admonish Kroc through his formal choices. The Founder is a bright and hopeful-looking film, whereas Anderson and Fincher reflected the moral horrors of their narratives through an appropriately gloomy, occasionally scary presentation. Perhaps McDonald’s refused to allow their namesake without some control over how it was used, or perhaps Hancock simply chose to produce another of his populist based-on-a-true-story productions.

Regardless of the specific ethical consequences related to McDonald’s, Kroc and his empire represent a dramatic change in America’s capacity for greed and ambition that seems all-too-commonplace today, particularly given the state of the union. Acknowledging the cost of this new paradigm seems like a minimum requirement for such a story. However, Hancock once again avoids digging into his subject with anything approaching a critical eye. Even if The Founder had contained the energy and formal bravura advertised, the script’s lack of perspective on the material would still have meant the film had failed to tackle its subject matter sufficiently. Setting aside the multi- and extratextual factors of the film, Hancock’s capable production offers an effortless viewing experience, thanks in large part to Keaton’s outstanding performance. Offerman and Lynch deserve high praise for their performances as well. If only the actors had given their performances to a film with something to say.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review