The Flash

By Brian Eggert |

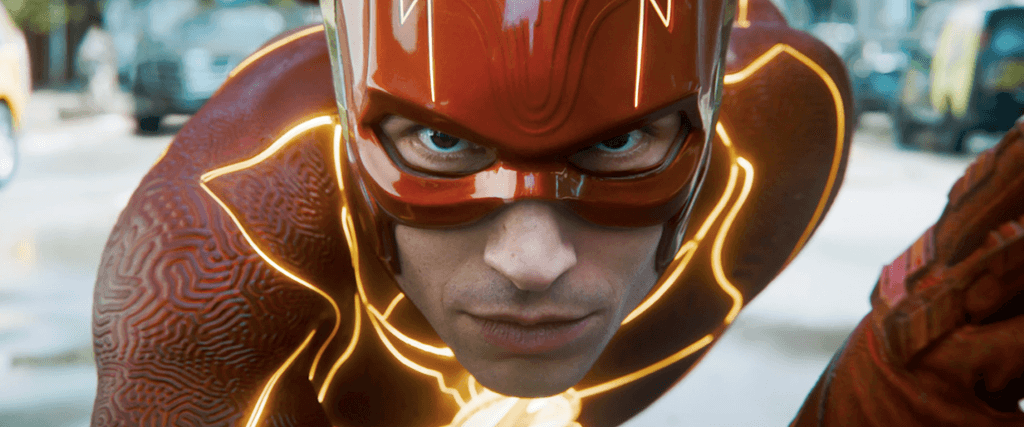

After two television series and years of development, the DC Comics superhero The Flash finally receives a feature film. Refreshingly, The Flash dispenses with the gloomy mood usually associated with DCEU fare, replacing it with a mishmash of multiversal and time-travel logic, self-aware humor, and enough references to appease the vocal fanbase. The movie also features a baby in a microwave, awkward virgin energy, and faster-than-the-speed-of-light running scenes depicted in slow motion. Yes, this is a weird blockbuster, even spoofy at times. But somehow, it’s fitting that Ezra Miller stars, playing the hyperactive superhero with a penchant for zippy behavior and motor-mouthed dialogue. Miller’s volatile presence aligns with the movie’s throw-everything-at-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks approach, deploying the randomness of the tired multiverse concept to an erratic and not altogether satisfying effect. One must admire the ambition involved in a production that’s not straightforward; rather, it zig-zags in bizarre directions that do little to improve on the DCEU’s unfocused overarching franchise. While far from a creative breakthrough, The Flash has its moments, including a worthy theme that not every problem can be solved with superpowers.

With the movie arriving two weeks after the similarly themed Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, Hollywood’s current obsession with multiverses now feels as commonplace as intergalactic titans (Thanos, Darkseid) seeking an all-powerful weapon to destroy the universe were a few years ago. But when the DCEU copies the MCU, it’s carrying on the decades-long tradition of DC Comics and Marvel Comics stealing from each other. For instance, after DC launched Green Arrow in 1941, Marvel created its own bow-and-arrow-wielding hero, Hawkeye, in 1964; after Marvel introduced Sub-Mariner in 1939, DC came up with Aquaman in 1941. The examples are endless. So, after the MCU used the multiverse in Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021) to bring three variations of the Web-Head together, the DCEU couldn’t ignore the capitalistic crossover potential. After all, besides the awesomeness of seeing variants from other timelines interact, it’s also smart corporate synergy. Once Disney acquired Marvel and 20th Century Fox, it would have been bad business not to splice their franchises, opening the door for other established heroes, such as the X-Men and Fantastic Four. Likewise, Warner Bros. realized they have over 40 years of cinematic DC iconography to play with, so why not exploit it?

Moreover, given the ailing state of the Zack Snyder versions of these heroes over the last decade, it probably seemed logical to both squeeze out as much brand recognition as possible while also pressing the reset button on the DCEU, using the multiverse device as a business tool to restart several franchises at once (Superman, Batman, etc.). Besides those lofty ambitions, The Flash also serves as an origin story of sorts, since Miller’s version of the eponymous hero never received one—even though their Barry Allen already appeared in several entries, beginning with Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016). So there’s a lot of pressure on The Flash, not only to deliver in narrative terms on the complexity of multiverse storytelling, but also in terms of series rearrangement. No wonder it boasts a typically long, 144-minute runtime. Still, no matter how entertaining The Flash can be at times, it’s difficult not to see the executive strings pulling the story in a particular direction out of a need for Warner Bros. to revisit lucrative intellectual properties.

Moreover, given the ailing state of the Zack Snyder versions of these heroes over the last decade, it probably seemed logical to both squeeze out as much brand recognition as possible while also pressing the reset button on the DCEU, using the multiverse device as a business tool to restart several franchises at once (Superman, Batman, etc.). Besides those lofty ambitions, The Flash also serves as an origin story of sorts, since Miller’s version of the eponymous hero never received one—even though their Barry Allen already appeared in several entries, beginning with Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016). So there’s a lot of pressure on The Flash, not only to deliver in narrative terms on the complexity of multiverse storytelling, but also in terms of series rearrangement. No wonder it boasts a typically long, 144-minute runtime. Still, no matter how entertaining The Flash can be at times, it’s difficult not to see the executive strings pulling the story in a particular direction out of a need for Warner Bros. to revisit lucrative intellectual properties.

Behind the scenes, The Flash has had a long road to the screen, going back decades. The DCEU version alone has undergone several false starts, including those by directors Seth Grahame-Smith and Rick Famuyiwa, who both left after parting with Warner Bros. over “creative differences.” The screenplay, too, has been ever-evolving. Christina Hodson receives sole screen credit, while John Francis Daley, Jonathan Goldstein, and Joby Harold take “story by” credit. But many more writers contributed in some way or another to the script’s development, drawing from the popular Flashpoint storyline from the comics. Watching the movie, one notices remnants of shifting tones from past drafts, some humorous, some serious. All of this might suggest that The Flash would end up a mess, pieced together from parts of countless drafts over the years. But Hodson—who also wrote Birds of Prey (2020), one of the better DCEU movies—delivers a cohesive story that keeps all the multiverse mumbo-jumbo straight, and it’s serviceably directed by Andy Muschietti (the two It movies). But there are other aspects about The Flash that don’t fare so well.

The basic story involves Barry Allen’s desire to prove his father (Ron Livingston, taking over for Billy Crudup) innocent of killing his mother (Maribel Verdú, from 2001’s Y tu mamá también) years earlier. The incident has prompted Barry, currently serving as the “janitor” of the Justice League, to seek a day job in a crime lab, hoping to find forensic evidence that proves the wrongly accused innocent. It also prompts him to run so fast that he reverses time, despite receiving a warning about playing with timelines from Bruce Wayne (Ben Affleck). Barry figures that if he can just make a small alteration to the past, he can ensure that his mother survives, and his father never has to face a murder trial. Instead, Barry breaks the universe. He saves his mother but accidentally winds up in the past, in an alternate timeline no less, just days before General Zod (Michael Shannon) begins terraforming Earth in Man of Steel (2013). Well, sort of. Anyway, Barry teams with his 18-year-old self to locate the Justice League, stop Zod, and restore the timeline—an unlikely feat given the spaghetti metaphor used to describe what he’s done to the multiverse.

With massive scope and stakes, and a reported budget north of $200 million, The Flash doesn’t look like a contemporary blockbuster. The CGI is especially bad in some sequences, if not embarrassing. Take a scene from early in the film involving falling babies; they look like monstrous siblings of that dancing baby screensaver from 25 years ago. Later, when Barry enters what he calls the “Chrono Bowl,” a vast kaleidoscopic arena where he can see alternate timelines playing out, the rendering of these branches enters Uncanny Valley territory—complete with melty-faced characters who look like they were designed for a Playstation 3 game. The effect returns multiple times in the movie and even supplies the location of the climax. But it’s underwhelming when Barry glimpses the many alternate universes out there, and he sees superheroes from throughout television and film history—icons of the screen come back to life—albeit animated with CGI that makes them seem like silly looking throwbacks to Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf (2007). The fights, too, seem less cinematic than inspired by video games like Injustice: Gods Among Us (2013), right down to a few recognizable moves.

With massive scope and stakes, and a reported budget north of $200 million, The Flash doesn’t look like a contemporary blockbuster. The CGI is especially bad in some sequences, if not embarrassing. Take a scene from early in the film involving falling babies; they look like monstrous siblings of that dancing baby screensaver from 25 years ago. Later, when Barry enters what he calls the “Chrono Bowl,” a vast kaleidoscopic arena where he can see alternate timelines playing out, the rendering of these branches enters Uncanny Valley territory—complete with melty-faced characters who look like they were designed for a Playstation 3 game. The effect returns multiple times in the movie and even supplies the location of the climax. But it’s underwhelming when Barry glimpses the many alternate universes out there, and he sees superheroes from throughout television and film history—icons of the screen come back to life—albeit animated with CGI that makes them seem like silly looking throwbacks to Robert Zemeckis’ Beowulf (2007). The fights, too, seem less cinematic than inspired by video games like Injustice: Gods Among Us (2013), right down to a few recognizable moves.

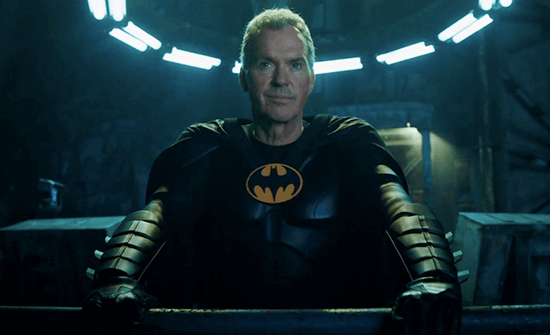

What The Flash bungles in franchise reconstruction and formal execution, it gets right in fan service and momentary pleasures. Writing about Across the Spider-Verse, I’ve already remarked on how multiverse scenarios serve fandom, offering baskets of empty Easter eggs for die-hard fans to discover. The same is true here, with the movie making countless throwaway references, turning the experience into an intertextual smorgasbord designed to delight fans able to find them all. There’s also a hefty helping of nostalgia poured on top like gravy. Warner Bros. paid the 71-year-old Michael Keaton a reported $10 million to reprise his role as Batman from the 1989 and 1992 movies, only to have him repeat famous lines like, “You wanna get nuts? Let’s get nuts.” Still, Keaton’s considerable presence in the movie’s second half, accompanied by notes from Danny Elfman’s iconic score, can’t help but generate some warm memories. The same goes for Affleck in Batman’s blue-gray costume, the brief return of Gal Gadot as Wonder Woman, and a nod to Eric Stoltz. Less impressive is Sasha Calle as Supergirl, a moody and undeveloped character with too little screen time to leave an impact.

Through it all, Miller is a constant source of energy, alternating between amusingly animated to Barry’s description of himself as “abrasive and exhausting”—particularly in the teen version of the character. Even so, Miller manages some laugh-out-loud bits of physical comedy, interspersed with occasionally grating inflections, making for an uneven but mostly enjoyable experience overall. Fortunately, The Flash is such a peppy hodgepodge of a movie that it’s enhanced by Miller’s additions to its manic energy. The result never quite satisfies as a stand-alone movie, and as a slate cleaner for a new cinematic universe, it never resolves the messy continuity issues thanks to a downright confusing last scene, implanting a sense of continued indifference toward the DCEU and its future. Yet, fans will enjoy its playful humor and superhero geekdom. The Flash is diverting enough to keep the casual viewer involved, while the superhero movie fanatics will no doubt respond with hyperbole.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review