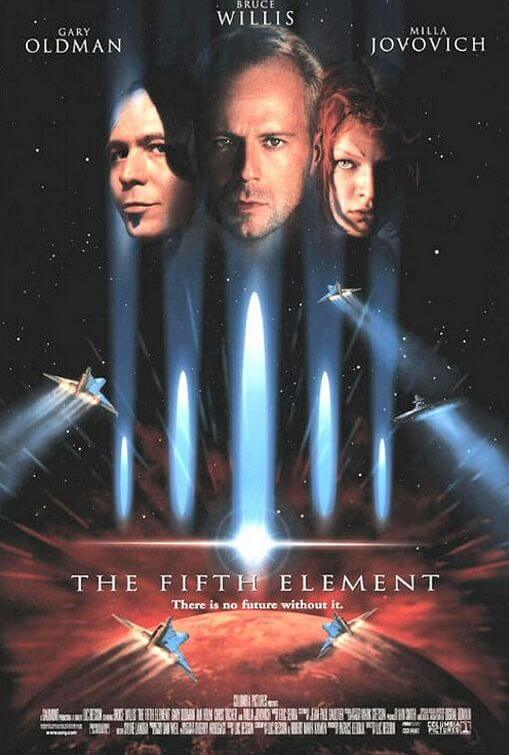

The Fifth Element

By Brian Eggert |

The 1990s exploded with The Fifth Element, writer-director Luc Besson’s big, colorful, silly production that’s more about absurd, eye-popping visuals than telling a good story. But any quibbles we might have about the lacking plot are flooded away by the overdose of aesthetics, clearly conceived with little but boldness and vastness and a fun-loving spirit in mind. You have to respect a film that goes so far over-the-top and doesn’t falter except in its moments of buffoonish peculiarity. As if cyberpunk and Star Wars had been tossed into a cotton candy machine, the film could easily be criticized as a product of stylistic self-indulgence—more accurately artistic masturbation—except, the ride is just too damn fun. With its choppily percussive editing and a color palette of space-aged Skittles, this $90 million Gaumont release (the most expensive of its kind at the time, 1997) contains a pointedly European cartoon flair and, regardless of its eccentricities, earned plenty at the box-office, and stands today as a watchable lark.

The story involves the type of unconditional conflict between Good vs. Bad that can only be designated by capital letters: Every five hundred years a prophesied Great Evil threatens to destroy the universe. Luckily there’s a Supreme Being, named Leeloo (Milla Jovovich, from Resident Evil), who concentrates the Four Elements (Earth, Fire, Wind, and Water) into a Divine Light that will stop this Great Evil (a psychic black planet with the ability to cause bleeding from the scalp). Makes sense, right? But the toddler-voiced, jittery, and hyperactive Leeloo, awakened in the year 2263, needs some help, despite her supremeness. Enter ex-military man-turned-taxicab driver Korben Dallas (a bleach-blonde Bruce Willis playing the future’s John McClane) who’s looking for the perfect girl. His ability to blow away bad guys comes in handy when attracting Leeloo. Expert in all things Supreme Being-related, Priest Vito Cornelius (Ian Holm) trails along, determined to protect Leeloo himself.

As for bad guys, there’s the seedy Zorg (Gary Oldman), an industrialist with a Southern drawl and his hands in everything from black market weaponry to mischievous deeds in the name of the Great Evil. Zorg and the Earth government (headed by the President, played by Tom Lister, Jr.) are in a deadly race to obtain four stones. (Is it a coincidence that this European production’s “American” characters are either evil Southerners, muscle-bound political leaders, or one-note action heroes? I think not.) When placed in a particular alignment with Leeloo, the stones have been prophesied to stop the Great Evil. But there are other concerns too. I haven’t even mentioned the lizardy mercenary aliens the Mangalores, flamboyant disc jockey Ruby Rhod (Chris Tucker, whose performance is wonderfully terrible), or the curious appearance of Luke Perry. They’re all fashion victims thanks to gaudy, futurist costumes designed by Jean-Paul Gaultier.

Having produced and directed a number of both French- and English-language films over the years, Besson, a Frenchman, abandons his usual temperance and poetic touch. Watching his competitive deep sea diving picture The Big Blue, made in 1988, we see his ability to circulate around and gently submerge his audience in the subject; with The Fifth Element, Besson dunks our heads under, nearly drowning us, and doesn’t let up until the last possible moment. Besson’s best pictures are marked with a balance between action and emotion, described most movingly by his popular narrative guise: the hitman-with-a-heart-of-gold theme explored both in La Femme Nikita and Léon (aka The Professional). We can thank Besson for introducing the world to both Natalie Portman and the ultra-cool Jean Reno in the latter, a tragically dark fable punctuated with a spree of bullets and falling tears. The Fifth Element is like Léon (and almost every other Besson film) in that it’s a well-paced action movie about a tough hero rescuing a young woman.

Having produced and directed a number of both French- and English-language films over the years, Besson, a Frenchman, abandons his usual temperance and poetic touch. Watching his competitive deep sea diving picture The Big Blue, made in 1988, we see his ability to circulate around and gently submerge his audience in the subject; with The Fifth Element, Besson dunks our heads under, nearly drowning us, and doesn’t let up until the last possible moment. Besson’s best pictures are marked with a balance between action and emotion, described most movingly by his popular narrative guise: the hitman-with-a-heart-of-gold theme explored both in La Femme Nikita and Léon (aka The Professional). We can thank Besson for introducing the world to both Natalie Portman and the ultra-cool Jean Reno in the latter, a tragically dark fable punctuated with a spree of bullets and falling tears. The Fifth Element is like Léon (and almost every other Besson film) in that it’s a well-paced action movie about a tough hero rescuing a young woman.

And while the manic, seemingly out-of-control pace nearly drops the viewer out of this sci-fi adventure, Besson’s wild images alone are just enough to keep us clinging to the ledge by our fingertips. Doing his best to achieve epic sci-fi status, Besson follows in the footsteps of his betters from the aforementioned Star Wars to Blade Runner, creating mythologies and writing whole languages for his characters. Not that we have the time necessary to stop and appreciate the fine details. We’re too busy spinning along with the film’s psychedelic color wheel and keeping up with the offbeat slapstick humor. Besides, his made-up Divine language seems like gibberish and his mythology like a videogame plot line, both awash in the breakneck pace that’s matched only by the passages of color and violence bursting onscreen.

It all flies by at impossible speeds, welcoming repeated viewings to catch every visual facet. We lose ourselves in the bustling flying car chases amid the air traffic of the future’s New York City, impossibly easy gun battles that are more exercises in making Willis look badass, and those body-bending feats in martial artistry composed by Jovovich. Adding to Besson’s kinetic energy is the music, conceived primarily of Middle Eastern melodies infused with dance floor percussion by Eric Serra, Besson’s frequent composer, which occasionally delves into a sort of corny sitcom theme. Fight scenes play like a music video, with diegetic and non-diegetic music working joyously in unison. One sequence intercuts Leeloo battling gnarly aliens on a space cruise liner, on the other side of which a techno-operatic concert performed by the blue, tendril-laden diva Plavalaguna (Maïwenn Le Besco) conveniently scores the fight. Punches connect on beat, the tempo picks up with the violence, and they both conclude with applause.

As irresistible—if occasionally annoying—popcorn-munching escapism, The Fifth Element remains an experience of diversionary entertainment, and almost exclusively about rehashing previously explored surfaces with a new sheen. Bruce Willis’ hero doesn’t need character development because he’s played this role before, perhaps dozens of times. The Earth metropolis doesn’t need an intricate survey because it’s assembled from pieces of Metropolis and Blade Runner (specifically the large-scale McDonald’s monitor, which echoes the Coke ad in Ridley Scott’s film). Any question about the story’s interplanetary system of worlds and how they relate to each other is clarified in such a brief shorthand that the viewer feels no need or interest to explore the idea further. From start to finish, we laugh and cheer and ooh and ahh at the pretty colors, explosions, and movement onscreen—all composed with breathtaking effects for their time, but nothing much backs them up. Even still, the experience leaves you drained in that way only an effective escape can achieve. Sometimes that’s all viewers need.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review