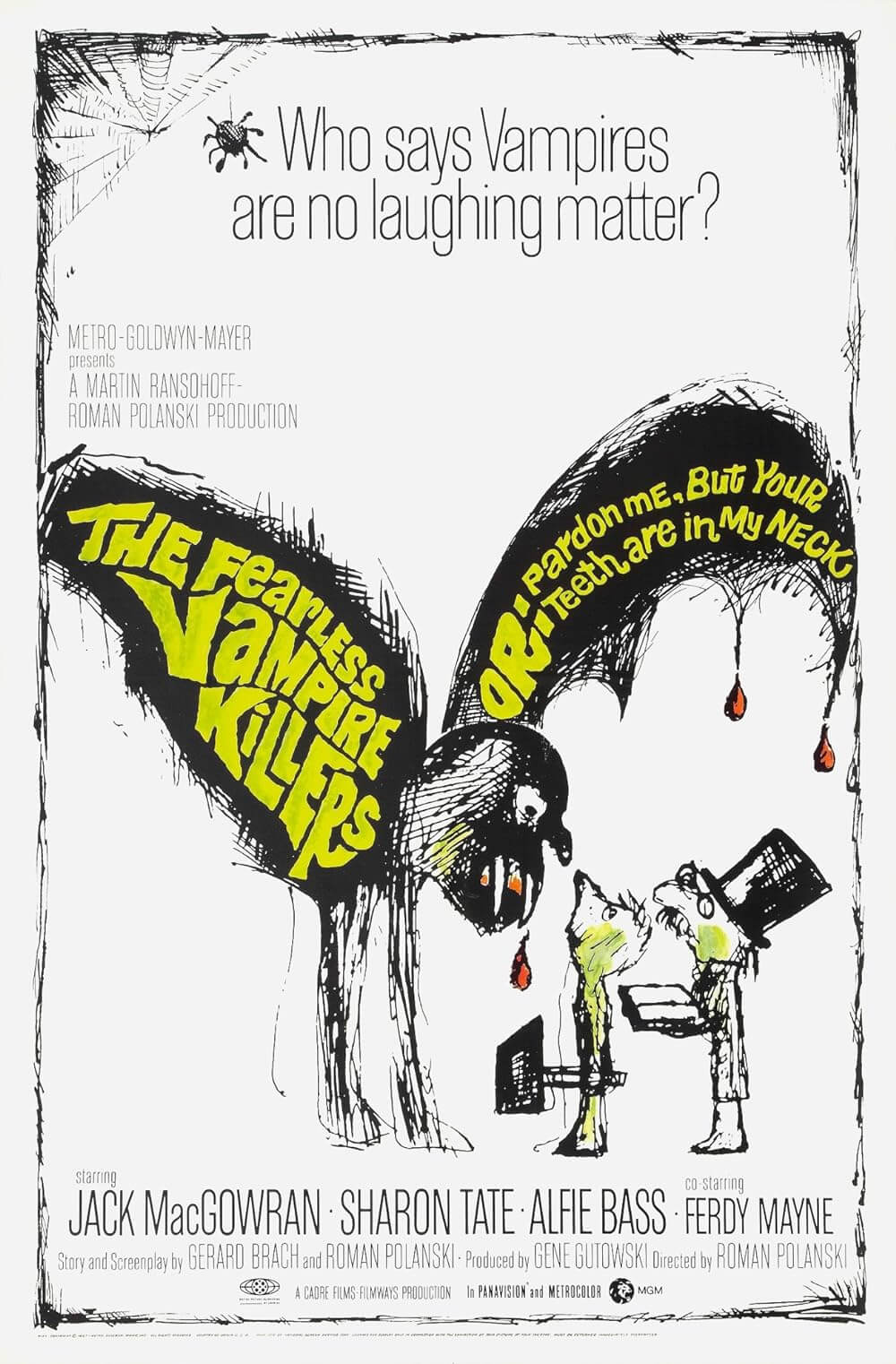

The Fearless Vampire Killers, or Pardon Me, But Your Teeth Are in My Neck

By Brian Eggert |

One of the most endearing parts of Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers, his odd little parody of Hammer horror films, is the presence of Sharon Tate, and the sheer joy she seems to experience as the object of affection for both the viewer and Polanski. Her role as Sarah, the innkeeper’s daughter, is luminous: Polanski shoots her in light that flatters and shimmers, capturing her in the bathtub or through a frosted window. Ultimately, she’s doomed by the fangs of the resident vampire, Count von Krolock. While her scenes could be accused of reducing Tate into a superficial role, her extratextuality enhances her scenes. Sarah’s thematic importance in the film, the director’s affection for Tate, her life with Polanski off-screen, and her own ability to command the viewer’s attention despite a limited character make The Fearless Vampire Killers a film marked by her presence.

Tate also has the same quality in The Fearless Vampire Killers that Margot Robbie has playing her in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino’s 2019 film. Their lines may be few, their characters central yet peripheral to the action involving each film’s two male leads, but somehow each version of Tate embodies an essential thematic component in their respective films. As I watched Tarantino’s ode to 1969, I found myself thinking about her incandescent quality in Polanski’s film. She resonates with the pleasure of looking beautiful, particularly for Polanski; the attention it brought her as the “it” girl on the film; and pride in her work.

The Fearless Vampire Killers is a weird and uneven film that has taken me several viewings to appreciate fully and not just endure impatience. Marked with a distinctly Central European flavor, the film stars Jack MacGowran as Professor Abronsius, the resident Van Helsing. Polanski co-stars as Alfred, Abronsius’ boyish and hapless manservant. When the two vampire hunters rest at a Transylvanian inn, they discover the locals live in fear of Count von Krolock (Ferdy Mayne), an intimidating Dracula type. Eventually, von Krolock kidnaps Sarah and plans to feed her to his blood-sucking clan, but Abronsius and the enamored Alfred come to the rescue.

The film emerged out of the 1960s brand of farcical comedy, complete with a Pink Panther-esque animated opening and sped-up chases worthy of The Benny Hill Show. Even the full title, The Fearless Vampire Killers, or Pardon Me, But Your Teeth Are in My Neck, reeks of the decade’s kooky mainstream humor. Polanski also had a curious love of slapstick, evidenced here in the numerous bonks on the head, pratfalls, and the dynamic between von Krolock’s predatory son and Alfred that begins to resemble Pepé Le Pew and Penelope Pussycat. The film’s best joke belongs to the Jewish innkeeper who, after being turned into a vampire, is confronted when his victim tries to defend herself with a crucifix: “Boy, have you got the wrong vampire!” Is this the first time a Jewish vampire laughed off a cross? I think so.

But Polanski’s attention to detail elevates the production. The set-pieces used to create the ramshackle inn and the vampire’s castle outdo most Hammer productions of the era featuring Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing. Polanski fills the screen with a series of grotesque faces worthy of Pieter Bruegel for his supporting cast. Patrons of the inn appear unsightly and bulbous, their faces hideous and exaggerated. Art historians will note the presence of Quentin Matsys’ The Ugly Duchess hanging in von Krolock’s castle, an obvious source of inspiration. Elsewhere, the finale’s dance of the vampires sequence, with rotting undead figures engaged in a dress ball, is a stunner.

In the mid-1960s, Polanski was hugely famous even before he arrived in Hollywood. A wunderkind fresh off his Polish thriller Knife in the Water from 1962, he had taken 1960s London by storm. There, he shot Repulsion (1965), an unforgettable psychological thriller starring Catherine Deneuve as a paranoid agoraphobe. He was at the center of Britain’s “youthquake” fashion movement, drove fast cars, kept company with the trendiest people, and enjoyed the attention afforded him by his celebrity. He was also busy making one film per year. While promoting Repulsion in 1966, he was making Cul-de-sac, his morbid and offbeat comedy about a criminal who invades the home of a secluded couple. And while promoting Cul-de-sac, he was making The Fearless Vampire Killers, the film that would introduce him to Tate.

In the mid-1960s, Polanski was hugely famous even before he arrived in Hollywood. A wunderkind fresh off his Polish thriller Knife in the Water from 1962, he had taken 1960s London by storm. There, he shot Repulsion (1965), an unforgettable psychological thriller starring Catherine Deneuve as a paranoid agoraphobe. He was at the center of Britain’s “youthquake” fashion movement, drove fast cars, kept company with the trendiest people, and enjoyed the attention afforded him by his celebrity. He was also busy making one film per year. While promoting Repulsion in 1966, he was making Cul-de-sac, his morbid and offbeat comedy about a criminal who invades the home of a secluded couple. And while promoting Cul-de-sac, he was making The Fearless Vampire Killers, the film that would introduce him to Tate.

Polanski had purchased a small home in London, just around the corner from the apartment where Tate was staying. The production company Filmways had arranged her lodgings on Eaton Place while she made the folk horror yarn Eye of the Devil (1966) and the Tony Curtis comedy Don’t Make Waves (1967). At the same time, Polanski was negotiating with Filmways about his vampire farce, which was called The Dance of the Vampires in Britain. Polanski and Tate met at a party of Filmways people and exchanged numbers. Not long after, they had dinner together, went back to Polanski’s place, took acid, and made love. The rest, as they say, is history.

Tate was an inexperienced actress when she appeared in The Fearless Vampire Killers. She always would be. In her youth, she had been a homecoming queen, a cheerleader, and later a model. Then she pursued acting, landing roles on popular television series like Mister Ed, The Beverly Hillbillies, and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. after meeting Filmways co-founder Martin Ransohoff. Despite this early success, she was racked with anxiety, often biting her fingernails. Her nervousness didn’t inhibit her, though. By all accounts, she was both insecure and unbound. “What had impressed me most about her,” Polanski wrote in his autobiography, Roman by Polanski, “quite apart from her exceptional beauty, was the sort of radiance that springs from a kind and gentle nature. She had obvious hangups yet seemed completely liberated. I had never met anyone like her before.”

In The Fearless Vampire Killers, Tate’s role as Sarah symbolizes innocence and beauty taken by an ugly force of evil, and Polanski, who fell in love with her on the set and films her as though she’s an emblem. She’s first glimpsed in a bathtub at the inn (“I got into the habit at school,” Sarah says), a tantalizing peek that assures Alfred’s continued attention. Later, Alfred, in the courtyard making a snowman, spies her looking down at him from a window. Snow gently falls on the scene, which is set to lovelorn humming on the soundtrack. It’s transfixing.

Alfred is enchanted, almost haunted by her. It is her image behind the falling snow and her love that incites Alfred to draw a heart on the frosted window, and her allure that compels Alfred to reference his pocket edition of A Hundred Goodlie Ways of Avowing One’s Sweet Love to a Comlie Domozel. After Count von Krolock takes her, it is her blood on the bubbles of her bath that drives Alfred to action, her ethereal song in the halls of von Krolock’s castle that wakes him at night, and her spell that causes him to ignore the bite marks on her neck. Sarah is everything to Alfred. And I can’t help but feel that the burgeoning love between Tate and Polanski enhanced this quality of her character in immeasurable ways, both in terms of what we see on the screen and the extratextuality we recognize as viewers.

Tate, or her character anyway, has a similar effect in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Tarantino uses her to evoke the spirit of 1969. And so her presence in the film is cheerful—full of life and upbeat possibility. Watch the scene where Robbie’s version of Tate goes to see herself in an afternoon matinee of The Wrecking Crew (1968), one of her only major roles and a bright example of her comedic chops. With her bare feet resting on the seat in front of her, Robbie’s Tate savors the laughter in the lightly attended moviehouse, her smile brimming with pride. Wisely, Tarantino uses actual footage of Tate’s role in The Wrecking Crew instead of digitally inserting Robbie opposite star Dean Martin. It’s almost as though we see Robbie appreciate Tate’s undeniable onscreen charisma from outside of the diegesis.

Tate, or her character anyway, has a similar effect in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Tarantino uses her to evoke the spirit of 1969. And so her presence in the film is cheerful—full of life and upbeat possibility. Watch the scene where Robbie’s version of Tate goes to see herself in an afternoon matinee of The Wrecking Crew (1968), one of her only major roles and a bright example of her comedic chops. With her bare feet resting on the seat in front of her, Robbie’s Tate savors the laughter in the lightly attended moviehouse, her smile brimming with pride. Wisely, Tarantino uses actual footage of Tate’s role in The Wrecking Crew instead of digitally inserting Robbie opposite star Dean Martin. It’s almost as though we see Robbie appreciate Tate’s undeniable onscreen charisma from outside of the diegesis.

Both roles, Tate and Robbie performing as Tate, are figurative. After all, Sharon Tate was more often than not objectified in her few Hollywood roles. She deserved better and only just began to show signs of something more than an attractive surface. A brief scene in Tarantino’s film takes place in a book store where Tate buys a copy of Thomas Hardy’s controversial Tess of the d’Urbervilles for Polanski, hoping he’ll adapt it for her (he did, albeit in 1979, with Nastassja Kinski). Tate’s performance was haunting in Eyes of the Devil, and she was downright tragic in 1967’s Valley of the Dolls, her most substantive role.

If The Fearless Vampire Killers teaches us anything—besides the lesson that Jewish vampires are impervious to crucifixes—it’s that Tate had the rare ability to take a largely dimensionless part and mesmerize her audience with her charisma in front of the camera and life off-screen. Finding this quality in her work today requires some searching outside of the text, but it’s there in the biographical and historical details, and the effect she has on her audience even today. What remains is her presence, both in the film and her life beyond it, and how it has been remembered.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review