The Father

By Brian Eggert |

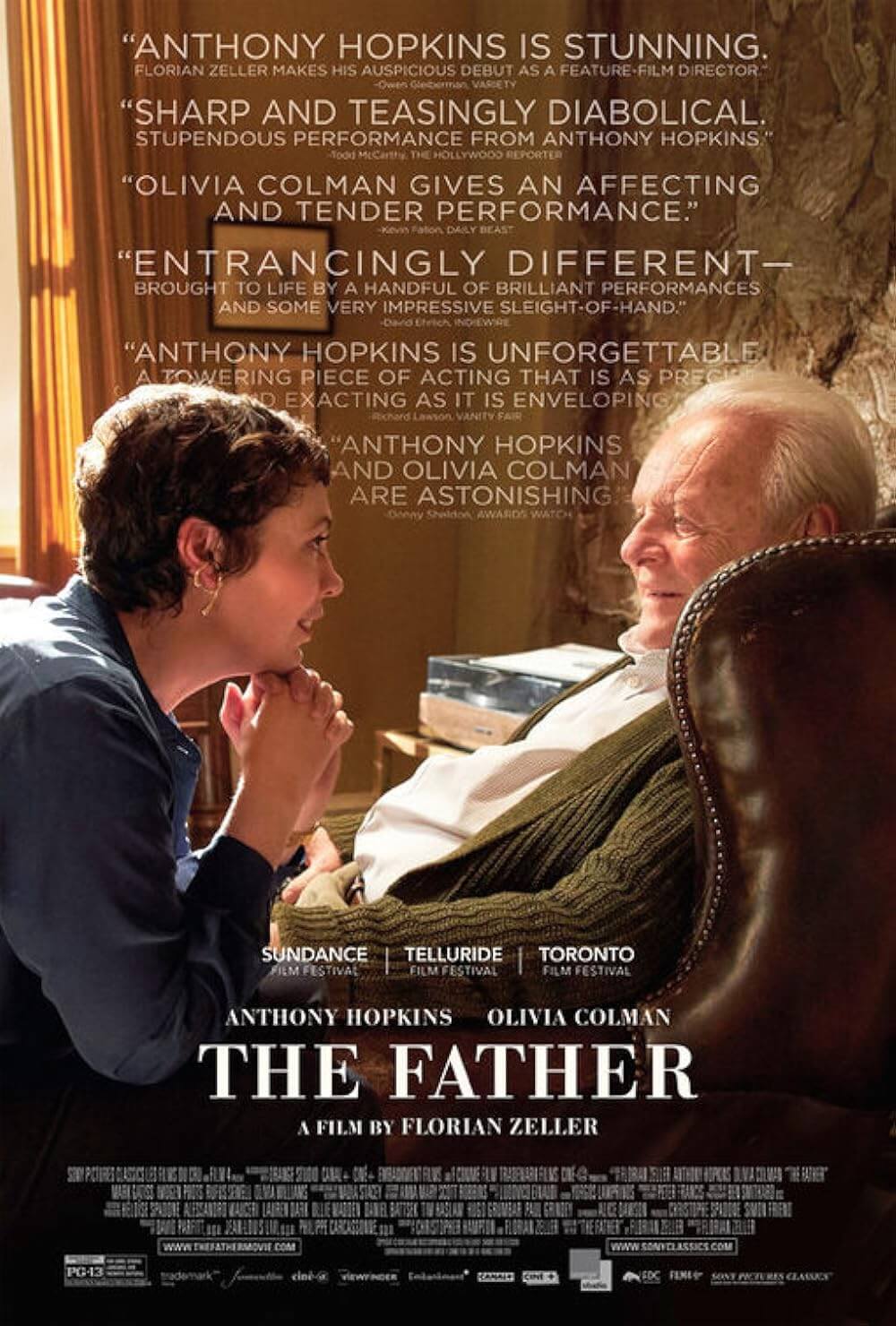

Several films over the past few years have confronted the reality of degenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. They require performers to capture incomplete characters, people who are losing themselves to the effects of dementia—memory loss, gaps in time, lack of concentration, and failed reasoning skills. Sarah Polley’s Away from Her (2006) featured Julie Christie in an Oscar-nominated performance as a woman who loses all memory of her former self and marriage. Julianne Moore won the Best Actress Oscar for Still Alice (2014), playing a linguistics professor who ironically loses her sense of speech to the disease. The latest of these dramas, The Father, feels no less Oscar-baity but takes an alternative approach to a similar story. It’s structured according to the disjointed mental state of its central character, Anthony, played by Anthony Hopkins, who gives his best performance in decades. The film’s complete immersion into his mental state offers a heartrending look at the disease by capturing the patchwork of names, faces, and places that Anthony struggles to connect.

Based on Florian Zeller’s 2012 play (Le Père), the film is also Zeller’s directorial debut. It’s an incredibly accomplished, well-structured chamber drama, aided in its translation to English by playwright and screenwriter Christopher Hampton (A Dangerous Method). The film begins with Anthony’s daughter, Anne (Olivia Colman), visiting him at his London flat. Although he insists “everything is fine” and he can manage on his own, his forgetfulness becomes apparent. He misplaces his prized watch and makes accusations when he cannot locate it. He’s also grown stubborn, angrily dismissing the latest in a string of nurses Anne has hired for him. His behavior is a growing concern for Anne, who feels guilty about being burdened by her father’s decline. Nevertheless, she moves him into her flat, much to the displeasure of her husband. Except, Anne’s flat bears an uncanny resemblance to Anthony’s flat, bringing into question how long Anthony has been living there. As The Father unfolds, it becomes clear that the film itself has been situated in Anthony’s subjective experience.

In other words, we see the idea of Anne and her apartment, but it’s unclear if the viewer is actually seeing them or if Anthony’s memory has blended one face and place with another. It’s disorienting when Anne comes home from shopping one afternoon and is no longer played by Colman, but rather Olivia Williams—prompting us to wonder whether two Olivias were cast as Anne to confuse the audience further. Anne’s husband, Paul, first appears as Mark Gatiss, but later, he’s played by Rufus Sewell. The uncertainty continues as scenes repeat themselves, mixing up when the scene originally took place and who was involved. At some point, Anthony’s watch was stolen. Was it stolen by Paul, or the nursing attendant Bill, also played by Gatiss? Did Paul or Bill slap Anthony during an argument? Is Anne really leaving for Paris to live with a man she’s met, or has she been married for some time? One of the nursing attendants, Laura, initially seen as Imogen Poots, looks like Anthony’s other, favorite daughter, Lucy, a world-traveling artist who was in some sort of accident—an incident that he sometimes remembers, sometimes doesn’t. There’s no telling to which character Poots’ face belongs, but the gradual realization of Anthony’s confusion aches.

Although the shifts in casting and location represent Anthony’s muddled sense of recognition, the film also employs a brilliantly subtle set design of familiar hallways, paintings, doors, and rooms. The Father takes place almost exclusively in blandly welcoming interiors, with some rooms in Anne’s flat decorated like a doctor’s office or nursing home, giving way to transition from one to the next. The attentive viewer will notice slight variations in the view out the window, the change in beds, or how Anne’s flat and the doctor’s office have the same door. The set and art decoration have been superbly blended and mixed up from scene to scene, creating uncertainty about what happened where and when. Zeller goes to such incredible lengths to portray Anthony’s perspective that it seems odd when he includes scenes alone with Anne, or Anne and her husband—they feel misplaced in the proceedings because they break our immersion into Anthony’s point of view.

Although the shifts in casting and location represent Anthony’s muddled sense of recognition, the film also employs a brilliantly subtle set design of familiar hallways, paintings, doors, and rooms. The Father takes place almost exclusively in blandly welcoming interiors, with some rooms in Anne’s flat decorated like a doctor’s office or nursing home, giving way to transition from one to the next. The attentive viewer will notice slight variations in the view out the window, the change in beds, or how Anne’s flat and the doctor’s office have the same door. The set and art decoration have been superbly blended and mixed up from scene to scene, creating uncertainty about what happened where and when. Zeller goes to such incredible lengths to portray Anthony’s perspective that it seems odd when he includes scenes alone with Anne, or Anne and her husband—they feel misplaced in the proceedings because they break our immersion into Anthony’s point of view.

The most impressive aspect of The Father is how Zeller keeps the viewer rapt in the emotional tone of any given scene instead of trying to unlock the patchwork of memories in Anthony’s mind. Each scene’s immediacy owes much to the actors—Hopkins and Colman were both nominated for Oscars for their work here—who convey each moment with a rewarding naturalism. Alas, this is betrayed by Ludovico Einaudi’s string score, which at times plays like the music to a paranoid thriller, creating tension in the viewer, as though we’re on the cusp of discovering some great conspiracy against Anthony. At other times, it creates links between scenes, a familiar series of notes that connect to an emotion from an earlier scene. Nevertheless, Einaudi’s music feels overly emphatic (just as it did in Nomadland), putting too fine a point on emotions, whereas no score at all may have been a more confronting and poignant choice.

What happened when and to who is less important than the central dramatic arc of The Father: it’s a story about a father and daughter, and as the father’s health declines, the daughter’s life begins to disintegrate as well. Eventually, she must find a way to say goodbye. Perhaps The Father‘s biggest surprise is how Hopkins manages to catch the viewer unprepared for his vulnerable performance. His character remains somewhat mysterious, with a past clouded by his condition. Is he just being playful with the new nurse when he tells her he used to tap dance or perform in the circus? Or is that some version of himself so distant that it now seems like another person? When the final scene comes, Hopkins manages to completely devastate the viewer with a breakdown that reflects how the aged often return to a state of childlike dependency. It’s a stirring piece of acting in a drama of finely tuned performances and accomplished filmmaking.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review