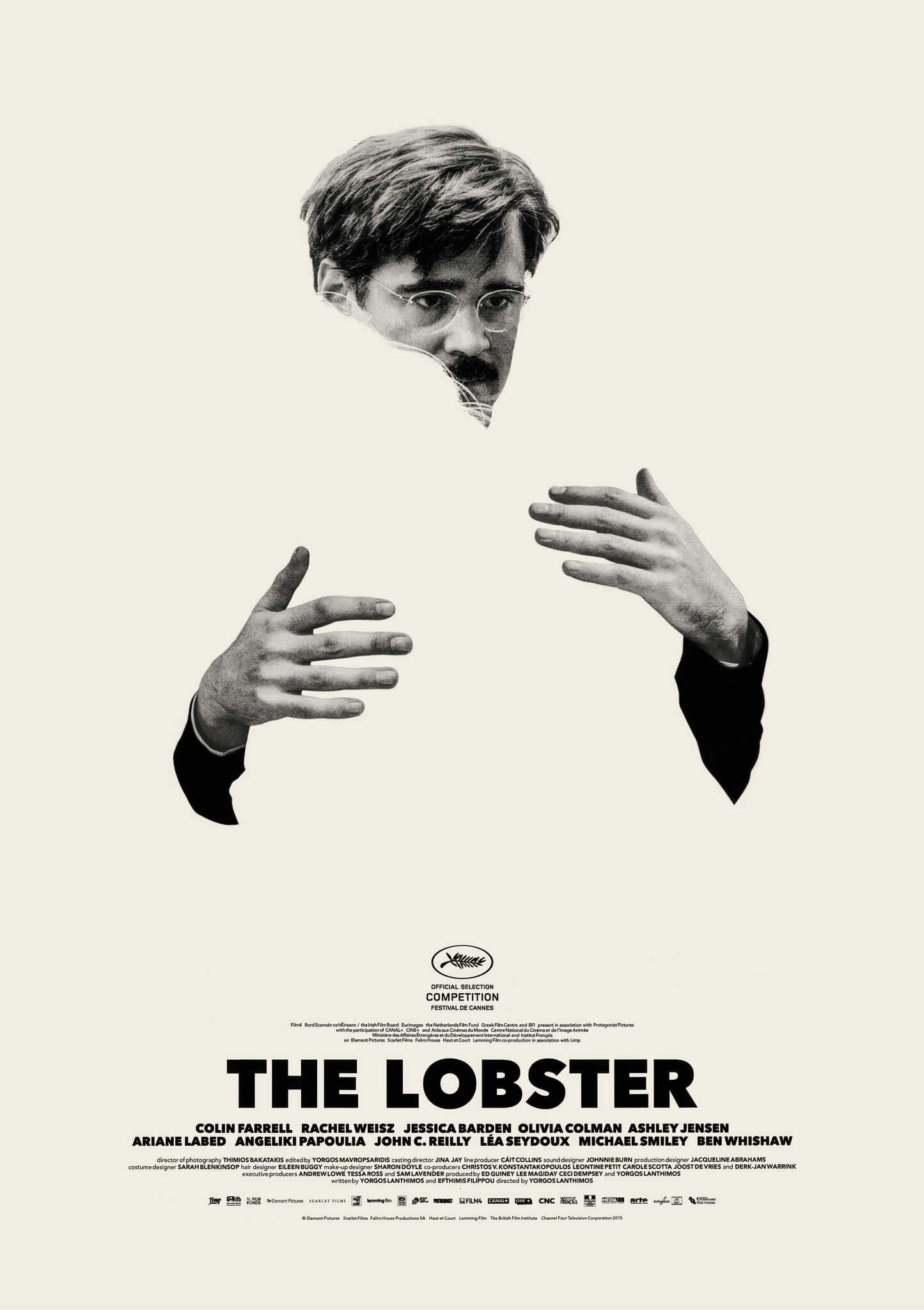

The Family Fang

By Brian Eggert |

With its melancholy score by Carter Burwell, The Family Fang tells a humorous yet substantive dysfunctional family story. Burwell, a frequent contributor to the Coen brothers’ body of work, and more recently Charlie Kaufman’s stop-motion animation wonder Anomalisa, uses of woeful oboes to channel all the pain and lingering unfulfillment of the film’s two siblings, whose roles as test subjects in an experimental artist family have left them to inherit a wealth of middle-aged hang-ups. Destined to be grouped alongside Wes Anderson’s superior The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) and Noah Baumbach’s more resonant The Squid and the Whale (2005)—both films about talented families reigned over by an often cruel paterfamilias—the film’s dramatic downturns are thoroughly counteracted by its play staging of the titular family’s unique, and often hilarious, performance art. And Burwell, one of today’s greatest scorers, turns the proceedings into a wounded elegy with his music.

Director-star Jason Bateman conjures a tender dramedy from Kevin Wilson’s 2011 novel of the same name. Nicole Kidman’s Blossom Films company purchased the film rights to Wilson’s book and hired David Lindsay-Abaire, who wrote the Kidman vehicle Rabbit Hole in 2010, to adapt. Though less stylistically ambitious than Anderson’s aforementioned dysfunctional family film, and less dark than Baumbach’s, Bateman’s second directorial effort demonstrates his growth as a filmmaker. His sweet-if-foul-mouthed debut Bad Words (2013) showed Bateman could juggle sentimentality in otherwise harsh conditions, but The Family Fang contains several layered performances and doesn’t rely on an overt gimmick (in Bad Words, Bateman played a man who participates in children’s spelling bees). Instead, it’s as richly complicated as the most alarming family dynamic.

Siblings Annie (Kidman) and Baxter (Bateman) were dubbed “Child A” and “Child B” when they were growing up. They were given no choice but to participate in the avant-garde performance art conceived by their parents. Take the pre-title flashback to the 1970s that shows the eminent New York artists Caleb and Camille (the younger versions played by Jason Butler Harner and Kathryn Hahn) at work. Caleb gives his wife and young children a pep-talk for what’s about to happen (his motto: “If you’re in control, the chaos will happen around you, not to you”), and there’s talk of fake blood and how to behave dead. Then we see the 9-year-old Baxter (Mackenzie Brooke Smith) attempt to rob a bank of its lollipops at gunpoint, resulting in the innocent death of a bystander, played by his own mother. While the bank patrons don’t take kindly to faux robberies and death in the name of performance art, Caleb believes the truest art resides in creating random, expressive moments in everyday life.

In the subsequent thirty years, Caleb and Camille made a name for themselves as social commentators and pranksters, while Annie and Baxter put distance between themselves and their parents. Christopher Walken (at his mischievous best) and Maryann Plunket play the older Caleb and Camille Fang, whose divisive output has lessened in the years since they’ve performed pieces with their children. In the subsequent years, Annie has grown up into a Hollywood actress of modest celebrity, while Baxter is working on his second novel. Not long after being reunited with Caleb and Camille following a long estrangement, the siblings’ parents appear to have been the victim of a killing. Unsure whether this is another performance piece or the real deal, Annie and Baxter begin to dissect their upbringing, their participation in their parents’ performance pieces, and their resentment of their lack of a normal childhood.

Several amber-hued flashbacks to the family’s various projects and performances shed light on the contemporary storyline. Cinematographer Ken Seng shoots them to look like 8mm or videotape recordings, taking us back into Annie and Baxter’s decades-old memories, while using similar footage when the siblings rewatch their parents’ documented artistic exploits. Bateman works alongside his editor Robert Franzen and knows just where to insert these moments—consider the sequence where, through a seemingly accidental series of events, a teenaged Annie and Baxter are forced to play Romeo and Juliet across from one another on their high school stage. Looking back, the Fang children must weigh the words of their play’s director, who was fired after the siblings’ on-stage kiss: “The best art always leaves scorched earth in its wake.”

The Family Fang may not leave behind scorched earth, but it effectively represents the scorched childhoods of Annie and Baxter. The brother-sister relationship remains the most engaging and tender portion of the film. These are raw, vulnerable roles: Kidman is excellent in her frantic investigation not only of her parents but Annie’s analysis of how she was at once encouraged to create yet painfully neglected; Bateman’s teary-eyed performance is far gushier with his character’s readings from his latest book. Fortunately, the film has much to say about what constitutes art, and how the level of one’s devotion to their vocation (art or otherwise) affects those around them. It’s a particularly meaningful film for anyone who has tried to balance their art with their personal life. Undoubtedly, that element is what drew the talented cast and skilled behind-the-scenes crew to the film, and what makes The Family Fang feel genuine.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review