The Exorcist: Believer

By Brian Eggert |

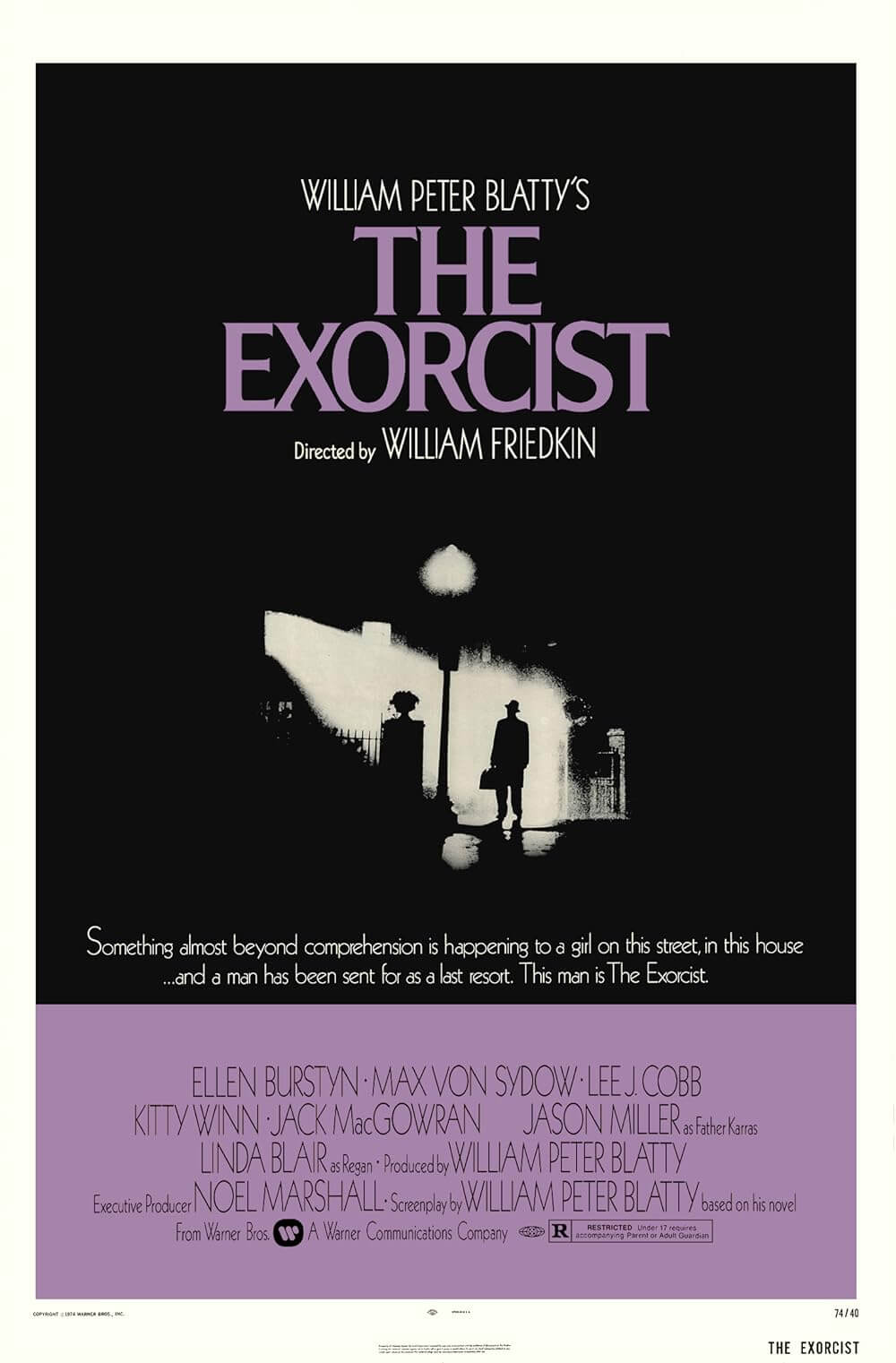

When The Exorcist debuted 50 years ago, audiences had never seen anything like it. The late William Friedkin’s film had shaken moviegoers to their core, both challenging and elevating preconceptions about what a horror movie could be. It reinforced the faithful and instilled a flicker of dreadful doubt among confirmed skeptics. The New Yorker critic Pauline Kael later described the film as “the biggest recruiting poster the Catholic Church has had,” which certainly helped the phenomenon become the highest-grossing film ever at that time. And in the half-century since its release, countless imitators have hoped to bank on The Exorcist’s cultural impact. Moviegoers have since seen one exorcism film after another—and not just in the two sequels or maligned prequel(s), but a whole subgenre of nasty exorcism pictures, most featuring young women possessed by a demon, making them contort their bodies and say awful things. This has become a cynical aspect of The Exorcist’s legacy. So when Blumhouse enlisted David Gordon Green, the director who made their new Halloween trilogy, to create a new Exorcist installment (and a reported two more to follow), he faced a challenge: Not only did he have to work in the shadow of the 1973 film, but he had to provide a direct sequel that somehow lived up to the original classic, while also accounting for the dozens of other exorcism movies since.

In that task, Gordon’s The Exorcist: Believer is not altogether successful. But it performs the obligatory duty of rebooting a franchise and making it once more commercially viable. Then again, perhaps “reboot” isn’t the right word. Scream fans might call it a “requel,” others a legacy sequel—they both revive a franchise and provide a sequel to the original, often using retroactive continuity. So, while things may be different, they’re also very much the same, reminding fans what they loved about the first film and reintroducing the milieu for those unfamiliar (the only people who might enjoy it). With those ambitions, the screenplay by Green and Peter Sattler deploys many hallmarks of the original with another innocent teenage girl (actually, two of them to up the ante) possessed by a demon; another urination scene; another uncomfortable, squirm-inducing medical examination; another look up at a second story bedroom window; more flashes of demonic faces; more flickering lights; more head spinning; and more disbelievers made into the faithful during the climactic exorcism. With all of those boxes checked, the film is suitably familiar apart from the particulars. The only problem is, it isn’t all that scary.

When The Exorcist came out, movie exorcisms were not so commonplace as they are today, and they certainly never featured anything so taboo as what Friedkin conceived (for instance, a 12-year-old girl stabbing herself in the vagina with a crucifix and yelling, “Let Jesus fuck you!”). Today, at least one exorcism movie is released each year, sometimes more (for recent examples, see last year’s The Seventh Day or this year’s The Pope’s Exorcist). We’ve seen the same maneuvers so many times by now that there’s nothing new to explore, and if there is, Green hasn’t done it. However, Believer offers a few worthy innovations. Note how his film’s message attempts an alternative lesson: it takes a village. The exorcism process is not merely about two men of the cloth doubling down on the Catholic Church’s views and rulebook about God; it’s about putting faith in other people and belief systems different than yours. The idea is that, no matter your beliefs, if enough people focus on the same outcome, they can rescue the possessed children at the film’s center. If that means a Catholic priest must work alongside an ex-nun, an atheist, and a mystic priestess, then so be it. Even so, that message proves superficial at best and self-conflicted at worst.

When The Exorcist came out, movie exorcisms were not so commonplace as they are today, and they certainly never featured anything so taboo as what Friedkin conceived (for instance, a 12-year-old girl stabbing herself in the vagina with a crucifix and yelling, “Let Jesus fuck you!”). Today, at least one exorcism movie is released each year, sometimes more (for recent examples, see last year’s The Seventh Day or this year’s The Pope’s Exorcist). We’ve seen the same maneuvers so many times by now that there’s nothing new to explore, and if there is, Green hasn’t done it. However, Believer offers a few worthy innovations. Note how his film’s message attempts an alternative lesson: it takes a village. The exorcism process is not merely about two men of the cloth doubling down on the Catholic Church’s views and rulebook about God; it’s about putting faith in other people and belief systems different than yours. The idea is that, no matter your beliefs, if enough people focus on the same outcome, they can rescue the possessed children at the film’s center. If that means a Catholic priest must work alongside an ex-nun, an atheist, and a mystic priestess, then so be it. Even so, that message proves superficial at best and self-conflicted at worst.

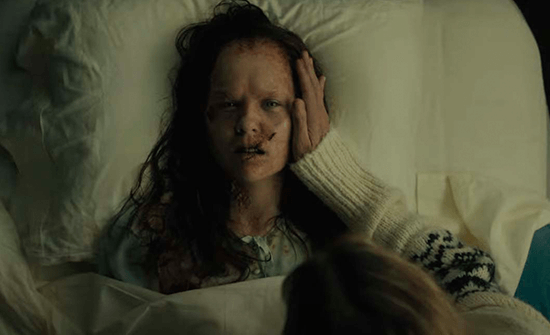

With a screen story conceived by Green, Danny McBride, and Scott Teems (who wrote 2021’s Halloween Kills together), the opening in Haiti finds photographer Victor (Leslie Odom Jr.) losing his pregnant wife in a disastrous earthquake, leaving him to raise their daughter alone. Many years later, Victor lives a comfortable life in Georgia with his surviving child, Angela (Lidya Jewett), who is now a teen and curious about her mother. Accompanied by her friend Katherine (Olivia Marcum), Angela disappears in the woods after school to contact her mother in a secret séance, using a candle, a pendulum, and a photograph. When the girls go missing and cause panic in the community, only to resurface three days later with no memory of where they’ve been, their erratic, inexplicable, and self-destructive behavior alarms the unbelieving Victor and Katherine’s religious parents—the shaken Miranda (Jennifer Nettles) and the combative Tony (Norbert Leo Butz), who believe Katherine visited hell while she was away like Jesus did after dying on the cross. While Katherine’s parents seek help from the church and their faith, Victor soon resolves to have Angela placed in a mental institution. It’s only upon the suggestion of Victor’s neighbor, the would-be-nun-turned-nurse Ann (Ann Dowd), that he searches outside his belief systems to find Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn)—the actress-mother of The Exorcist’s original victim.

In the decades since the first film’s events, Chris has given up acting and become an expert on the practice of exorcism in various cultures, at the cost of losing touch with her daughter, Regan (Linda Blair). And since Believer is a requel, it pretends that the events in Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) and The Exorcist III (1990) never happened. Chris’ presence feels ungainly inserted into the mix for fan service, given that halfway through, she’s brutally attacked and hospitalized for the remainder of the film. Leaving her out entirely may have given the filmmakers more liberty to experiment outside of the original story’s margins. Regardless, what unfolds is another showdown between the demon—Pazuzu, who still remembers Chris and at times evokes Regan—and a ragtag group that receives its strength from its diversity and togetherness. There’s a lot of meat in the room when the dull, climactic exorcism of the two girls begins, with Victor and his friend Stuart (Danny McCarthy) preparing the dining room location by securing two chairs together and then having the spiritualist Dr. Beehibe (Okwui Okpokwasili) draw chalk symbols on the floor. Once the Christians show up, the group throws a lot of exorcism spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks, but none of it is particularly thrilling.

Green’s direction is competent, and the actors all give serviceable performances, but the material has lost its edge, or at least it feels that way in Green’s hands. Cinematographer Michael Simmonds uses plenty of ominous shadows to disguise faces and ratchet up the fear that something will pop out at you. Editor Tim Alverson follows Friedkin’s playbook and inserts brief, unsubtle flashes of demonic faces that never prompt viewers to wonder, Did I just see that? It’s too obvious to miss. The score by David Wingo and Amman Abbasi serves the material, repurposing Jack Nitzsche’s iconic theme from the original. But somehow, Believer feels commonplace. Stories from the original film’s theatrical run include patrons fainting, walking out, or throwing up in the aisles. Writing from experience, watching The Exorcist for the first time shocks the system. But the novelty of onscreen exorcisms has passed, and the old tricks feel overdone. Along with prodding viewers with jump scares and an ugly use of CGI smoke and portals (or something), Green follows the visual grammar of movie exorcisms to a fault. The audience in my screening chuckled after every scare rather than shuddering in terror. They were used to this routine, and they weren’t disturbed in the least. So when Angela and Katherine begin to contort their bodies or hurl vile insults at the group of exorcists, it’s received with a certain ho-hum response.

Green’s direction is competent, and the actors all give serviceable performances, but the material has lost its edge, or at least it feels that way in Green’s hands. Cinematographer Michael Simmonds uses plenty of ominous shadows to disguise faces and ratchet up the fear that something will pop out at you. Editor Tim Alverson follows Friedkin’s playbook and inserts brief, unsubtle flashes of demonic faces that never prompt viewers to wonder, Did I just see that? It’s too obvious to miss. The score by David Wingo and Amman Abbasi serves the material, repurposing Jack Nitzsche’s iconic theme from the original. But somehow, Believer feels commonplace. Stories from the original film’s theatrical run include patrons fainting, walking out, or throwing up in the aisles. Writing from experience, watching The Exorcist for the first time shocks the system. But the novelty of onscreen exorcisms has passed, and the old tricks feel overdone. Along with prodding viewers with jump scares and an ugly use of CGI smoke and portals (or something), Green follows the visual grammar of movie exorcisms to a fault. The audience in my screening chuckled after every scare rather than shuddering in terror. They were used to this routine, and they weren’t disturbed in the least. So when Angela and Katherine begin to contort their bodies or hurl vile insults at the group of exorcists, it’s received with a certain ho-hum response.

Worse, Believer’s shallow attempt to instill a “we’re all in it together” message feels hollow when aspects of the film hinge on Christian morality—after all, a large segment of the ticket-buying audience will be part of a faith-based community that wants to see their morals and superstitions reinforced onscreen. Abortion-related revelations in the film find Victor and Ann judged for their respective actions, prompting guilt, condemning looks from the possessed children, and judgment from their fellow exorcists. Intentional or not, Green and his writers imply that a mother’s life is secondary to a child, shaming two characters who had to make difficult decisions concerning pregnancies. If the underwhelming scares weren’t enough, the morals of the religious right sour the otherwise tolerant message. Then again, Tony, ever unwilling to go along with any mumbo jumbo that isn’t Catholic mumbo jumbo, goes against his diversified band of exorcists, and it horrifically backfires on him.

Thematically, then, Believer tries to appeal to all sides in a decidedly noncommittal ideology. It’s not altogether surprising. For all of Friedkin’s braggadocio, he never minced his words or failed to take on his subject directly—his cinema was always head-on and confrontational. Green has a thornier and business-minded game to play, since Blumhouse and distributor Universal Pictures paid a reported $400 million for the Exorcist intellectual property to develop a trilogy and, eventually, house the films on their streaming service, Peacock. Ensuring a return on their investment means their movie shouldn’t piss anyone off. However, this is a miscalculation; some of what made the 1973 film such a cultural landmark and sensation, commercially and critically, was the controversy. Friedkin’s willingness to push boundaries and shake viewers out of their apathy served as an answer to that infamous 1966 issue of Time magazine asking, “Is God Dead?” Friedkin’s film convinced audiences that the devil existed, so God must too, right? Green doesn’t convince us of anything—aside from Hollywood’s rare ability to strip-mine franchises until they’re creatively barren.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review