Reader's Choice

The Ex-Mrs. Bradford

By Brian Eggert |

Why do classical Hollywood programmers go down smoother than today’s studio products? The Golden Age of movies operated like a magic factory, churning out smartly crafted pictures to meet the demands of audiences who regularly attended the cinema. Besides the radio, moviegoing was America’s primary pastime in the first half of the twentieth century. At its height of popularity in the late 1920s and early 1930s, upwards of 23,000 movie theaters spanned the country, compared to around 2,300 today. Studios raced to maintain a consistent flow of productions for distribution to and exhibition in theaters they owned. This practice ended in a famous 1948 antitrust case that put a stop to the block booking that discouraged competition. The studio system was a well-oiled machine that, given its regimentation, one might suspect would disperse hollow products due to their almost assembly-line construction. Perhaps the magic of this factorylike system is that most studio programmers from this era seldom feel like they were pieced together on an assembly line. They feel vibrant and alive, filled with charming stars and competent filmmaking. Whereas today’s studio products tip the scale between art and commerce to the latter, classic Hollywood programmers did not need product placements and corporate synergy. They were the product, and they were crafted with care, no matter how formulaic they could be.

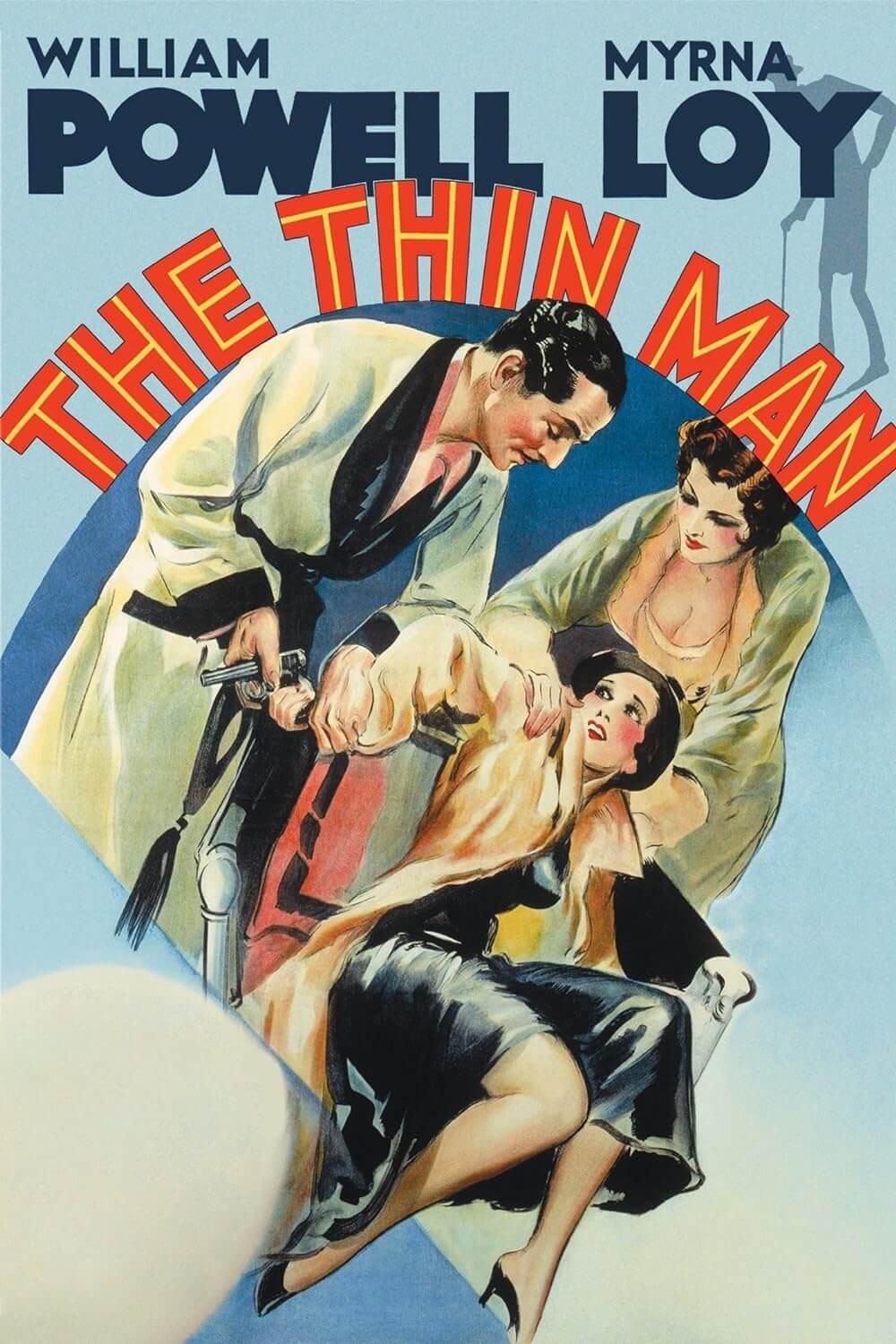

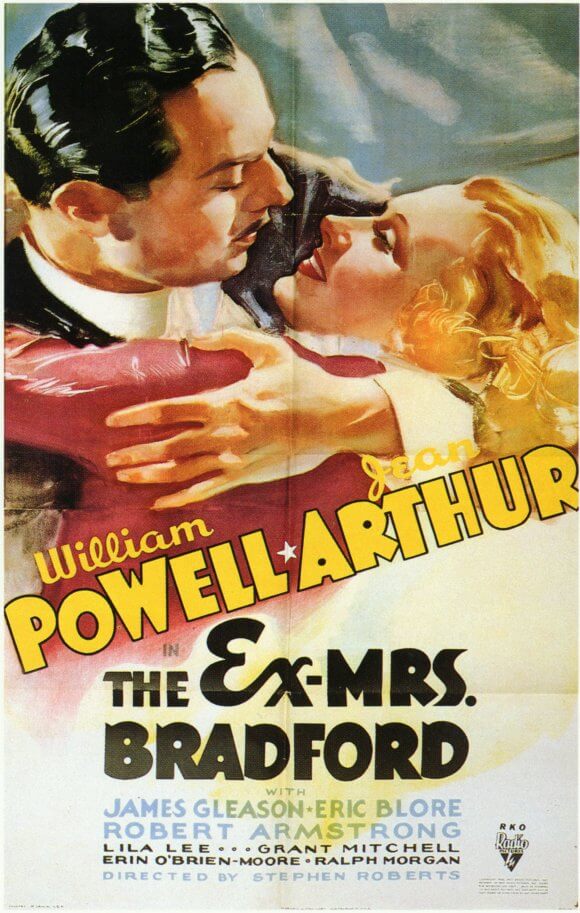

Consider The Ex-Mrs. Bradford, released by RKO Radio Pictures in 1936. By all accounts, it was RKO’s attempt to cash in on the popularity of the quick-witted The Thin Man (1934), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s box-office smash that delighted audiences and critics alike with its blend of murder mystery and comedy, anchored by the charming chemistry between retired detective Nick Charles (William Powell) and his New York socialite wife, Nora (Myrna Loy). Directed by Stephen Roberts, The Ex-Mrs. Bradford even stars Powell, who replicates his reluctant detective routine in a similar husband-wife dynamic, this time with a delightful, squeaky-voiced Jean Arthur. Not a review from the era fails to mention The Thin Man in its assessment of The Ex-Mrs. Bradford. The staff at Variety called such comparisons “natural” yet qualified, “The film is much better than a copy.” In the New York Times, Frank Nugent praised the film next to The Thin Man, arguing it “comes closest to approximating its gayety, impudence and ability to entertain” and is “one of the year’s top-flight comedies.” The many similarities between the two films might be distracting if The Ex-Mrs. Bradford wasn’t such an entertaining film and far superior to the other films that borrowed The Thin Man’s template.

Around the same time as The Thin Man, audiences saw several obvious imitators featuring a high-society couple that doubles as a detective duo investigating a murder in a glamorous setting. While MGM continued the adventures of Nick and Nora Charles into the late 1940s with five diminishing but no less entertaining sequels, other studios, including MGM, sought to replicate their appeal. Marco Page’s 1938 novel Fast Company, about a couple of rare booksellers, Joel and Garda Sloane, who moonlight as amateur sleuths, was adapted into a feature by director Edward Buzzell that year. The Sloanes returned in MGM’s Fast and Loose and Fast and Furious, both released in 1939. However, different actors played the characters in each installment: Robert Montgomery and Rosalind Russell in the former, Franchot Tone and Ann Sothern in the latter. MGM’s Fast series was never as popular as its competition, perhaps owing to the inconsistent cast. By contrast, audiences returned to each Thin Man installment not just for Nick and Nora Charles (and Asta!) but also to see Powell and Loy together again.

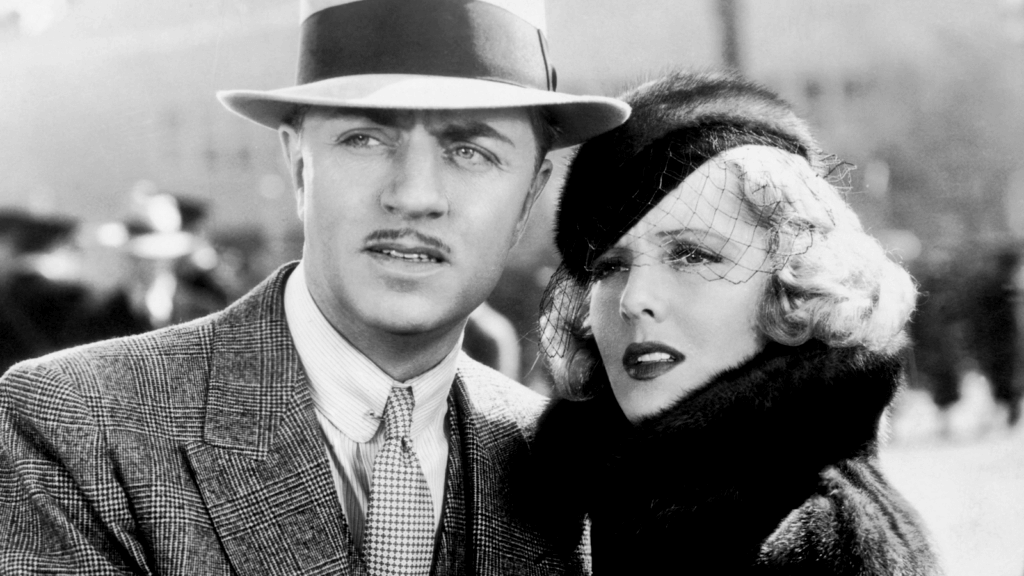

Between The Thin Man and its first sequel, After the Thin Man (1936), Powell had starred in a few pictures designed to bank on the original’s success, both for RKO. For instance, Star of Midnight (1935) found Powell opposite Ginger Rogers in another programmer for director Stephen Roberts. The story again follows socialites who help search for a missing dancer, only to find themselves wrapped up in a murder mystery. Powell, of course, had been a screen detective for years, such as in his 1928 talkie debut, Interference, after which he most notably starred in several pictures as detective Philo Vance. Alternating between serious crime yarns and comedies, Powell was versatile. The Thin Man wonderfully combined the actor’s strengths into a sensational blend. Other Thin Man copycats include Mr. and Mrs. North (1942), featuring Gracie Allen and William Post, Jr., about another pair of socialites who find a dead body in their liquor cabinet. The format became so ingrained as a Hollywood archetype that Woody Allen paid homage in Manhattan Murder Mystery (1994), a charming effort featuring Diane Keaton, Alan Alda, and Anjelica Huston.

Based on a story by James Edward Grant, The Ex-Mrs. Bradford, with a screenplay credited to Anthony Veiller, centers on renowned surgeon Dr. Lawrence “Brad” Bradford (Powell). His wife Paula (Arthur) divorced him because her career as a murder mystery writer kept getting him entangled in various real-life murder cases, which he found “intolerable.” She thought it was “fun.” Content to spend his evenings drinking and relaxing, aided by his beleaguered butler Stokes (Eric Blore), Brad is shocked to discover his wife is suing him for nonpayment of alimony. His excuse? She “already has two-thirds of the money in California.” Paula aims to remarry Brad, and, in the meantime, she moves into his apartment in exchange for alimony payments. Like Nora Charles, Paula is more than the classic Hollywood equivalent of a manic-pixie-dream-girl—she’s a progressive instigator in the relationship and screen story, wrestling her love interest out of his apathy to get him involved in the world at large. This time, Paula convinces Brad to examine a dead jockey who dies suspiciously of heart failure, though only two weeks earlier, Brad happened to have examined the victim and found no reason for alarm.

The mystery and subsequent victims involve a few innovative details, including the mysterious presence of gelatin, a racetrack murder, and, later, a black widow spider. Otherwise, the narrative structure follows The Thin Man right down to the finale, where Brad insists on bringing together all suspects to expose the culprit, borrowing a strategy from Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot. While the mystery proves clever and engaging, The Ex-Mrs. Bradford works mainly because Powell and Arthur have such effortless chemistry. The stars had appeared together previously in two Philo Vance mysteries, The Greene Murder Case and The Canary Murder Case, both in 1929, and the 1930 crime drama Street of Chance. But their onscreen pairing was never better than here, where the humor enriches their rapport. And if anyone could hope to compare to Loy—who starred in fourteen films with Powell—it’s Arthur, who handles the roles effortlessly. She embodies Paula as a loving foil who isn’t above playful insults (she calls him “sissy”) and affectionate critiques. Paula jabs at her husband in adorable ways, teasing him that he has always wanted to be a “boy detective.” One suspects that one of the reasons she divorced Brad is because he wasn’t adventurous enough for her, and prompting him to solve murders brings out that quality.

Even if the material and its type of characters have been done before, The Ex-Mrs. Bradford contains too much to admire in Veiller’s script and Roberts’ execution for the similarities to be a distraction. To be sure, even the heavy drinking of the Thin Man series carries over here, adding to the occasional silliness throughout. Several setups also prompt a laugh, such as Paula writing Brad a farewell note that says she’ll return in 10 minutes. The dialogue is consistently sharp and funny. Later, Brad asks, “What’s a cocktail dress?” His ex-wife replies, “Something to spill cocktails on.” Roberts also concocts a few memorable sequences that enrich the thrills. A shooting about mid-film has a kinetic quality that raises the tension. The visual highlight occurs during a racetrack sequence that finds Brad trying to capture the culprit on film. He arranges eight cameras to film the suspects interacting with the likely jockey target, and editor Arthur Roberts delivers a memorable montage that crackles with genuine suspense for the big event.

The Ex-Mrs. Bradford debuted in May and received impressive box-office receipts, enough to wonder why MGM didn’t continue the Bradfords’ adventures. Maybe the prospect was dampened by Roberts’ premature death by a heart attack at the age of 40 in 1936, two months after The Ex-Mrs. Bradford’s release. Throughout the 1920s, Roberts made short films before advancing to full-length features in the 1930s. He made some memorable films in those six brief years, most of which he spent at Paramount Pictures. Among his credits are the controversial classic The Story of Temple Drake (1933), featuring Miriam Hopkins as a fallen woman; the Gary Cooper vehicle One Sunday Afternoon (1933); and the Czech immigrant melodrama Romance in Manhattan (1934). Like many directors from the era, Roberts served as a studio journeyman, making whatever script his studio put before him. The Ex-Mrs. Bradford was the final film in his short-lived career, which deserves more consideration given the memorable titles to his credit.

Romanticizing classics such as The Ex-Mrs. Bradford comes easy when filmmakers are content delivering little more than escapist entertainment, occupying the familiar mode of screwball mystery-romance without constantly referencing its antecedents or selling the viewer a product other than the film itself. There’s something curiously satisfying about being served this sort of meal—one devoured many times before—yet it remains a comfort despite bringing nothing particularly new to the recipe. Though Powell and Loy’s collaborations would be more significant given the influence of the Thin Man series and their other collaborations, Powell and Arthur share a similar appeal as an onscreen couple. But then, Powell usually had that effect, evidenced in his pairing with Carole Lombard in My Man Godfrey (1936) and other leading ladies. One should not overlook Arthur’s appeal either; shining in several features by Frank Capra, Billy Wilder, and Howard Hawks over the years, she has an effervescent quality that she delivers here and in many of her roles. If the film is more of the same, it’s the best Thin Man copycat from this era, replicating with affectionate skill like a painting forged so well that it blurs the line between art and imitation.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on April 30, 2024. Thank you for your continued support, Elizabeth!)

Bibliography:

Bryant, Roger. William Powell: The Life and Films. McFarland & Company, 2006.

Francisco, Charles. Gentleman: The William Powell Story. St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

Harvey, James. Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, from Lubitsch to Sturges. Knopf, 1987.

Nugent, Frank S. “Two Slight Cases of Murder: ‘The Ex-Mrs. Bradford,’ at the Rivoli, and ‘The Case Against Mrs. Ames.’” The New York Times, 28 May 1936. https://www.nytimes.com/1936/05/28/archives/two-slight-cases-of-murder-the-exmrs-bradford-at-the-rivoli-and-the.htm/. Accessed 20 April 2024.

Variety Staff. “The Ex-Mrs. Bradford.” Variety, 31 December 1935. https://variety.com/1935/film/reviews/the-ex-mrs-bradford-1200411155/. Accessed 20 April 2024.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review