The Evil Dead

By Brian Eggert |

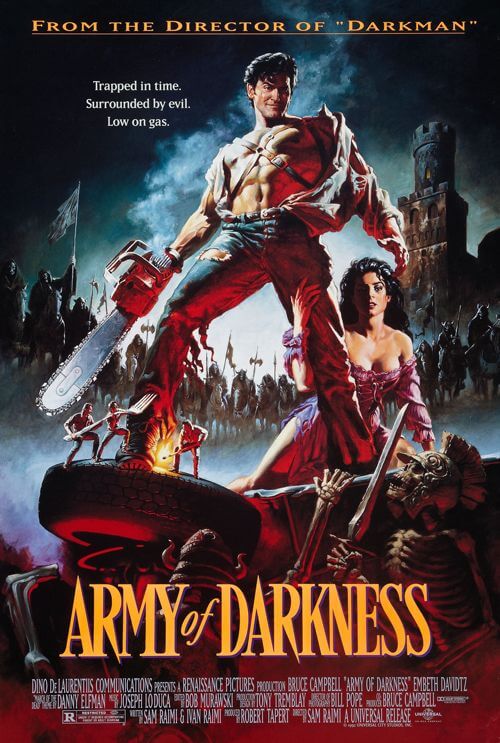

Cult classics have rarely earned more devotion than The Evil Dead, the first feature from Sam Raimi, director of the original Spider-Man trilogy and A Simple Plan (1998). Millions of fans have turned this low-budget cabin-in-the-woods horror yarn from 1982 into a phenomenon spawning two sequels, one remake, videogames, toys, and even a (quite good) musical. Around Halloweentime, you can usually find a theater showing the original, Evil Dead 2 (1987), and Army of Darkness (1992) in a back-to-back marathon. But with all the hullaballoo surrounding it, discussions of the film often veer into its subculture rather than the film itself. More ambush-style horror than the comic slapstick of its sequels, this is an artfully made and frightening experience punctuated by pools of soupy gore. The Evil Dead may not produce an intellectual response for its countless fans of the franchise, but the young Raimi’s innovative production and the directorial bravado on display are impossible to deny. It’s even more impressive when taking into account the shoestring budget and grueling conditions under which it was made. Here, the tenets of the director’s future visceral works seem fully developed and even confident, as though a seasoned master was finally allowed to test his craft.

Looking at the film today, it’s almost inconceivable how a 20-year-old filmmaker from rural Michigan assembled the means to complete his first motion picture, and not only complete it, but complete it with confidence that solidified his unique style. Born in 1959, Raimi grew up a movie brat, raised on a steady diet of movies, television, and the Three Stooges. As a teenager, he toyed with amateur magic and practiced parlor tricks on his friends and family, fascinated by how showmen disguised their illusions. He also made short films with schoolmates on his family’s Eastman Kodak 8mm camera. Eventually, he purchased his own camera with money he earned from raking leaves. Along with friends Scott Spiegel, Robert Tapert, Bruce Campbell, and brother Ted, among others, Raimi formed the Metropolitan Film Group, otherwise known as the “Michigan Mafia.” Together, they made a series of short films, largely slapstick, with punctuated titles like It’s Murder! to set apart their own brand of gonzo amateur filmmaking. To learn about the business, Raimi also apprenticed under advertising director Verne Nobles and soaked up every jot of information he could to enhance his understanding of the technical craft and industry tricks. As with many a short filmmaker, the time came when Raimi and company decided to produce their own feature-length film.

By the late 1970s, low-budget horror movies emerged as a genre with potentially huge box-office returns. Tobe Hooper and Wes Craven proved as much with their respective hits, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977). Raimi resolved to test himself in the genre, making the short Clockwork in 1978, a minimal slasher about a serial killer hunting a lonely woman. Taking a cue from Hooper and Craven, as well as George A. Romero’s independent hit Night of the Living Dead (1968), the young director and crew would spin a similar yarn about five college students vacationing in a cabin in the woods, where they would awake an ancient evil from its slumber. Before he dove into a feature, however, Raimi wisely produced the short Within the Woods, a condensed, 32-minute cheapie to show investors what to expect from Raimi’s first feature, originally titled Book of the Dead—a nod to the Necronomicon of Lovecraftian lore. On the strength of Within the Woods, Raimi consulted a family friend, lawyer Phil Gillis, on how to produce a film, and then he and his cohorts went to every friend and family member to solicit investments. They even secured a loan from a bank in Detroit. For their efforts, the young filmmakers assembled $90,000, and then, with their curiously short 14-page script in hand, began casting auditions in their parents’ basements.

By the late 1970s, low-budget horror movies emerged as a genre with potentially huge box-office returns. Tobe Hooper and Wes Craven proved as much with their respective hits, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and The Hills Have Eyes (1977). Raimi resolved to test himself in the genre, making the short Clockwork in 1978, a minimal slasher about a serial killer hunting a lonely woman. Taking a cue from Hooper and Craven, as well as George A. Romero’s independent hit Night of the Living Dead (1968), the young director and crew would spin a similar yarn about five college students vacationing in a cabin in the woods, where they would awake an ancient evil from its slumber. Before he dove into a feature, however, Raimi wisely produced the short Within the Woods, a condensed, 32-minute cheapie to show investors what to expect from Raimi’s first feature, originally titled Book of the Dead—a nod to the Necronomicon of Lovecraftian lore. On the strength of Within the Woods, Raimi consulted a family friend, lawyer Phil Gillis, on how to produce a film, and then he and his cohorts went to every friend and family member to solicit investments. They even secured a loan from a bank in Detroit. For their efforts, the young filmmakers assembled $90,000, and then, with their curiously short 14-page script in hand, began casting auditions in their parents’ basements.

Their deceptively simple story consisted of one-note characters facing a series of horrific and unpredictable trials, all designed to elicit potent reactions from the audience. In a remote cabin in the Tennessee woods, two couples—Ash (Campbell) and Linda (Betsy Baker), and Scott (Richard DeManincor) and Shelly (Theresa Tilly)—are joined by Cheryl (Ellen Sandweiss), Ash’s sister. In addition to being the fifth wheel, Cheryl finds herself rattled by a haunting presence in the woods chanting, “Join us.” Later, the group finds materials left in the cabin by a professor who unearthed the ruins of an ancient city called Kandar: a ceremonial knife, a Sumerian Book of the Dead woven in human flesh, and a tape recorder. When they listen to the tape, they discover the professor has recorded funerary incantations, and when played, they awaken a demonic Force within the woods. Even the woods themselves are possessed, as Cheryl learns when she goes out looking for the source of the chants and ends up raped by living trees. Unable to escape because their environment seems to have come alive to isolate them, the vacationers are possessed by the Force one by one and turned into monstrous tormentors who turn on one another in a series of relentless, jarring, and disgustingly gory primary-colored attacks. The friends must kill and dismember each other to stop the evil. By the end, the otherwise goofball Ash has become the lone hero, having killed his friends and decapitated his girlfriend to survive. But in the last sequence, one of Raimi’s frantic Force-perspective shots rushes upon Ash to claim him.

A proposed six-week shoot starting in October 1979 moved the crew from their homes in Michigan to Morristown, Tennessee, to avoid the cold Michigan winter. Except, this particular year was one the coldest in Tennessee and one of the mildest in Michigan. The thirteen-member cast and crew settled to a secluded spot in the woods in a ramshackle cabin with no electricity, running water, or heat. Given the script’s length, they relied on improvisation in sequence after sequence, as Raimi and company figured out how to accomplish what they wanted with their limited funds. Special FX guru Tom Sullivan quickly assembled masks, and the limited supplies often meant the actors needed to stay in makeup for days. The experience was famously punishing for all, but Raimi flourished in these conditions—the director admits that his creativity blossoms when he’s able to torture his actors. For the famous POV shots where the Force reels through the woods, cinematographer Tim Philo mounted their camera on a piece of wood and sprinted through a swamp. For the finale, when the Force races down a hill, through the cabin, and into Ash, the filmmakers secured the camera to a bicycle—which collided with Campbell when they filmed this shot. Gradually, the production’s funds were depleted, and everyone was staying longer than they had originally agreed. The Tennessee shoot finished by January 1980, but insert shots and reshoots still needed to be completed in Raimi’s basement and garage, while Sullivan took another 10 months to complete the stop-motion animation FX for the finale’s gore-splosion. Something to consider: these were not professional filmmakers, but people with day jobs and bills who, after principal photography, worked on finishing the film in their off-hours.

A proposed six-week shoot starting in October 1979 moved the crew from their homes in Michigan to Morristown, Tennessee, to avoid the cold Michigan winter. Except, this particular year was one the coldest in Tennessee and one of the mildest in Michigan. The thirteen-member cast and crew settled to a secluded spot in the woods in a ramshackle cabin with no electricity, running water, or heat. Given the script’s length, they relied on improvisation in sequence after sequence, as Raimi and company figured out how to accomplish what they wanted with their limited funds. Special FX guru Tom Sullivan quickly assembled masks, and the limited supplies often meant the actors needed to stay in makeup for days. The experience was famously punishing for all, but Raimi flourished in these conditions—the director admits that his creativity blossoms when he’s able to torture his actors. For the famous POV shots where the Force reels through the woods, cinematographer Tim Philo mounted their camera on a piece of wood and sprinted through a swamp. For the finale, when the Force races down a hill, through the cabin, and into Ash, the filmmakers secured the camera to a bicycle—which collided with Campbell when they filmed this shot. Gradually, the production’s funds were depleted, and everyone was staying longer than they had originally agreed. The Tennessee shoot finished by January 1980, but insert shots and reshoots still needed to be completed in Raimi’s basement and garage, while Sullivan took another 10 months to complete the stop-motion animation FX for the finale’s gore-splosion. Something to consider: these were not professional filmmakers, but people with day jobs and bills who, after principal photography, worked on finishing the film in their off-hours.

To assemble the footage, Raimi settled on a Detroit-based editing house where Edna Paul and her assistant Joel Coen (yes, that Joel Coen) produced the 85-minute cut, which the director first screened for rapt audiences at a local Detroit theater. To secure wider distribution, Raimi met with Irving Shapiro, a distributor who worked with everyone from Jean Renoir to George A. Romero. Shaprio provided funds for advertising, publicity shots, and a poster; he also insisted they rename their film, suggesting no one would want to see a film with “book” in the title. Of the several oddball names proposed (such as Lick the Blood Off My Shovel!), Raimi chose The Evil Dead. Thanks to Shapiro, The Evil Dead premiered out of competition at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival and, among other notices, received a stamp of approval from horror author Stephen King, whose enthusiastic review called it “ferociously original.” Without King’s endorsement, the film might never have gathered the interest of British distributor Stephen Wooley, longtime collaborator with The Crying Game (1992) helmer Neil Jordan. New Line Cinema also showed interest and distributed the film stateside. To avoid a proposed X-rating, The Evil Dead was released “unrated” into a limited number of theaters and became popular on the midnight movie circuit, slowly making around $2 million at the box office. Since filming, post-production, and promotion totaled $350,000, the film was something of a hit. And despite a few detractors accusing Raimi of exploitation for his “forest rape” sequence, critics responded admiringly. Los Angeles Times writer Ken Thomas called it “the gristliest well-made movie ever.”

Regardless of positive reviews and meager box-office profits, The Evil Dead would not become a cult classic until it became available to the video market. At home, underage horror fanatics could discover this scandalous “unrated” film on VHS, an attractive proposition until the “unrated edition” became an all-too-common marketing ploy. Video sales only increased as the years went on, reaching a curious height long after the two sequels, when, in 1998, The Evil Dead reached the #3 spot in DVD sales. Internet subcultures and videophiles had turned the franchise into a phenomenon fifteen years after the fact. Along with The Evil Dead series, star Bruce Campbell became a subculture unto himself. An old-fashioned-looking actor with comic wit and a heroic, prominent chin, it’s a pity he wasn’t born in 1910, because by 1930 he would’ve made one helluva leading man. Campbell became a self-styled icon of B-movies, writing two hilarious books about the film series and his status as a B-movie actor: If Chins Could Kill and Make Love! The Bruce Campbell Way. An enduring presence on television shows like The Adventures of Brisco County Jr. and Burn Notice, Campbell makes a cameo in nearly every Raimi film, and the director’s die-hard fans now expect to see “The Chin” in every movie, idolizing him largely on the strength of his performance in this series. Other frequent Raimi screen talent includes his brother Ted, and “The Classic”—a 1973 Oldsmobile Delta 88, the color of movie theater popcorn no less, which Raimi has maintained and rebuilt over the last few decades.

Regardless of positive reviews and meager box-office profits, The Evil Dead would not become a cult classic until it became available to the video market. At home, underage horror fanatics could discover this scandalous “unrated” film on VHS, an attractive proposition until the “unrated edition” became an all-too-common marketing ploy. Video sales only increased as the years went on, reaching a curious height long after the two sequels, when, in 1998, The Evil Dead reached the #3 spot in DVD sales. Internet subcultures and videophiles had turned the franchise into a phenomenon fifteen years after the fact. Along with The Evil Dead series, star Bruce Campbell became a subculture unto himself. An old-fashioned-looking actor with comic wit and a heroic, prominent chin, it’s a pity he wasn’t born in 1910, because by 1930 he would’ve made one helluva leading man. Campbell became a self-styled icon of B-movies, writing two hilarious books about the film series and his status as a B-movie actor: If Chins Could Kill and Make Love! The Bruce Campbell Way. An enduring presence on television shows like The Adventures of Brisco County Jr. and Burn Notice, Campbell makes a cameo in nearly every Raimi film, and the director’s die-hard fans now expect to see “The Chin” in every movie, idolizing him largely on the strength of his performance in this series. Other frequent Raimi screen talent includes his brother Ted, and “The Classic”—a 1973 Oldsmobile Delta 88, the color of movie theater popcorn no less, which Raimi has maintained and rebuilt over the last few decades.

Lost somewhere in the fanaticism surrounding The Evil Dead is the purity of technical filmmaking and personal style implemented by its director. With this first feature, Raimi breaks rules, creates new ones, and demonstrates profound confidence in his approach. For example, take the opening scene, when the vacationers drive on a winding road to their destination. Raimi innovates on the standard of cross-cutting between two elements to create tension by introducing a third element. He cuts back-and-forth from the college students in “The Classic” to an oncoming truck on a collision course to enhance the suspense. Raimi one-ups this traditional technique by adding a third element, a POV Force shot—a mysterious unknown presence watching from the woods. Doing this in any film is risky; making it work as the first scene in your movie might be genius. Raimi’s visual and narrative styles depend on unpredictability. He feeds on the audience expecting one thing, if only so he can deliver another. Later, on the forest trail to the cabin, we hear that typical heartbeat sound effect that’s corny but nevertheless builds suspense; when they arrive, we realize it’s not a heartbeat but a hanging porch swing thumping against the cabin from the wind. But then it stops all of a sudden. Something is very wrong. Has our heart stopped? It’s about to.

After about 20 minutes of watching these otherwise dull characters unpack for their weekend getaway, the small hints and unnerving sounds that suggest something is off begin to build. Cheryl is overcome by this unseen presence, which takes her over in a seizure and forces her to draw a crude rendition of the Necronomicon in her sketchbook. And then, once she heads out into the forest (following her Horror Movie 101 rulebook), Raimi’s unruly shock and awe campaign launches against the audience. To say Raimi takes the material over the top is an understatement. Cheryl’s forest rape alone is easily the most unsettling moment in Raimi’s career, so much so that he would later admit to going too far. Once the demons, known as “Deadites,” begin to possess the students, we realize there’s no traditional villain in the film. Friends become enemies, twisted into demon-like zombies, and we’re subject to a series of bloody expressions, mutilations, and unbelievably vivid violent acts with a shovel, fire poker, shotgun, Kandarian knife, and chainsaw. Raimi’s visual style is almost vaudevillian, his arrangement of shots, tilted angles, wide-angle lenses, breakneck editing, and in-your-face camerawork become dizzying and sometimes wildly cartoonish. He’s not above finding the occasional laugh amid the screams either, which is another way he toys with his audience. It’s a quality that lends the film its campiness yet also distinguishes it as self-aware satire.

After about 20 minutes of watching these otherwise dull characters unpack for their weekend getaway, the small hints and unnerving sounds that suggest something is off begin to build. Cheryl is overcome by this unseen presence, which takes her over in a seizure and forces her to draw a crude rendition of the Necronomicon in her sketchbook. And then, once she heads out into the forest (following her Horror Movie 101 rulebook), Raimi’s unruly shock and awe campaign launches against the audience. To say Raimi takes the material over the top is an understatement. Cheryl’s forest rape alone is easily the most unsettling moment in Raimi’s career, so much so that he would later admit to going too far. Once the demons, known as “Deadites,” begin to possess the students, we realize there’s no traditional villain in the film. Friends become enemies, twisted into demon-like zombies, and we’re subject to a series of bloody expressions, mutilations, and unbelievably vivid violent acts with a shovel, fire poker, shotgun, Kandarian knife, and chainsaw. Raimi’s visual style is almost vaudevillian, his arrangement of shots, tilted angles, wide-angle lenses, breakneck editing, and in-your-face camerawork become dizzying and sometimes wildly cartoonish. He’s not above finding the occasional laugh amid the screams either, which is another way he toys with his audience. It’s a quality that lends the film its campiness yet also distinguishes it as self-aware satire.

Composer Joseph LoDuca once described Raimi’s approach as a series of pranks. Whenever there’s a quiet moment in an Evil Dead film, expect the very next moment to leave you shocked, revolted, or laughing. Although The Evil Dead strives for more scares than laughs (whereas the sequels are increasingly more interested in comedy than inducing terror), Raimi’s embrace of the horror genre is never a one-note experience. His directorial touches and resourcefulness behind the camera incorporate a sly degree of innovation. Certainly, the plot itself presents a twist on traditional cabin-in-the-woods horror, where a masked killer cuts down unwitting students; the film’s internal threat alone is novel. Moreover, the squeamish and faint of heart should stay away, far away; the level of high-voltage horror energy Raimi wields is immeasurable and leaves one shaken upon first viewing. But the film’s true mark of distinction resides in Raimi’s kinetic control over the proceedings. If Alfred Hitchcock played his audience like a classical piano, Raimi plays us through a series of dissonant, off-key notes both startling and astonishingly original. The Evil Dead is an experience from which its strange effect, unique shifts in tone, and visual showmanship have been cemented in cult film history, and whose qualities remain impossible to duplicate, except perhaps by Sam Raimi himself.

Bibliography:

Campbell, Bruce. If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor. LA Weekly Books for St. Martin’s Press, 2001.

Muir, John Kenneth. The Unseen Force: The Films of Sam Raimi. Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2004.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review