The Eclipse

By Brian Eggert |

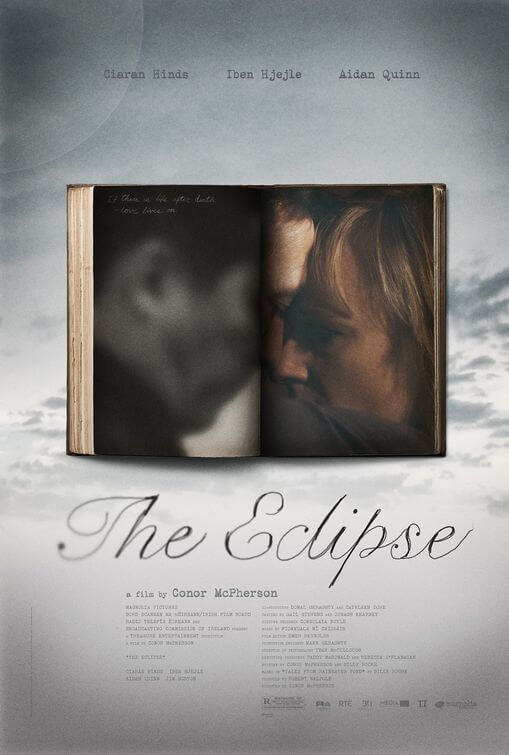

Part ghost story, part drama about middle-aged romance, part somber examination of loss, The Eclipse proves so subdued that putting one genre-specific label on the result does it an injustice. This quiet and eerily involving tale from Irish filmmaker Conor McPherson uses the supernatural, even a shocker moment or two, to tell a story that otherwise fully embraces the tone and atmosphere of a drama. The two styles wouldn’t seem to go together, but McPherson has crafted an unusually affecting film, one whose occasional horror imagery only heightens the emotional core.

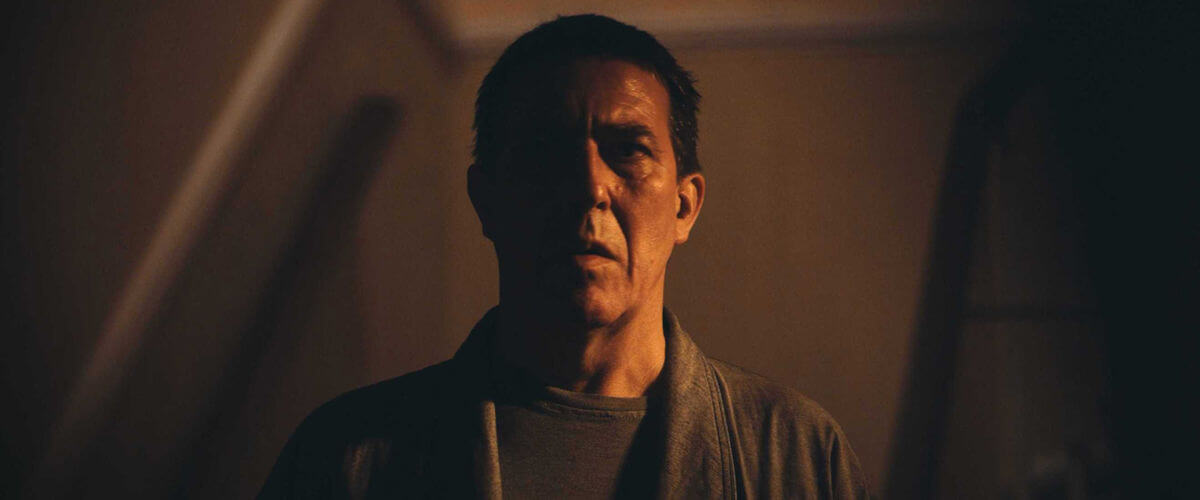

Ciarán Hinds, who frequently plays a supporting actor in fine pictures like Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day and There Will Be Blood, takes an infrequent yet welcome lead role in the film. Hinds plays Michael Farr, a widower, and father of two children. Still in mourning over his wife, who slowly died of cancer, he’s unable to let go of her memory. Reminding him of his wife is his father-in-law, who now fades away in an assisted care center for the elderly. In the night, Michael begins to hear sounds and see shadows that he believes are the spirit of his not-yet-dead father-in-law, but how can that be? Even those who believe in ghosts believe someone must be dead to have a wandering spirit.

Meanwhile, Michael has long since abandoned his own aspirations to be a writer for a quiet life. At his hometown’s annual literary festival, he acts as a gopher and drives around celebrity authors. Aidan Quinn plays Nicholas Holden, a brash, self-absorbed best-seller who anxiously waits to continue his fling with fellow writer Lena Morelle (Iben Hjejle), though she’s not interested in interrupting Holden’s marriage any more than she already has. Michael drives them both to and from their speaking engagements, enduring Holden and being attracted to Morelle. Eventually, Michael puts enough trust in Morelle to confess that he’s seeing spirits; since ghosts are the specialty in her books, she’s the perfect ear for his troubles.

What ensues alternates between a love triangle connecting Michael and the two writers, a meditative character study of the somber Michael reclaiming his life, and questions about life after death. The supernatural elements strangely work thanks to McPherson’s grave pitch, where lingering thoughts of death and the departed won’t let go of Michael. Interspersed into the drama are sudden jolts of rather horrific imagery, mostly of Michael’s father-in-law reaching out at him. But don’t consider these moments part of an underutilized horror element of the plot; consider them the shocking imagery of a drama about moving beyond the past and learning to live again.

Filmed under the ever-overcast skies of Ireland, the rainy film is comprised of little dialogue and long, thoughtful, wordless sequences that can’t help but draw our attention to the actors. Hinds may be an unlikely leading man, as his dark, long-faced features have made him a more believable movie villain than a romantic protagonist. But he carries impressive weight in his performance, and he’s likely to gain other leading roles because of his work here. For every understated gesture from Hinds, Quinn has an expression bubbling over with exuberant cockiness, extending his character almost into a caricature that doesn’t quite fit the story. Hjejle’s character is more restrained to match Michael, which helps to identify Quinn’s character as the evident oddball in the group of otherwise pensive roles.

It would be easy to condemn The Eclipse for its seemingly anticlimactic ending, as some critics have done, but that would be missing the point. The story doesn’t wrap up the burgeoning romance between Michael and Morelle, which is frustrating. Nor does it answer our questions about the ghostly, terrifying imagery. But it does bring a conclusion to Michael’s limbo—the emotional rut that he was well into as the film began. As the title suggests, the film only dwells on a brief moment in time for Michael, a dark in-between passage in his life. Once he says goodbye to his wife, he’s able to move on. The story is never more complicated than that. And yet, even if the plot is standard stuff, McPherson’s hushed, almost poetic treatment of the material has a way of getting under the skin and lasting long after the film has ended.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review