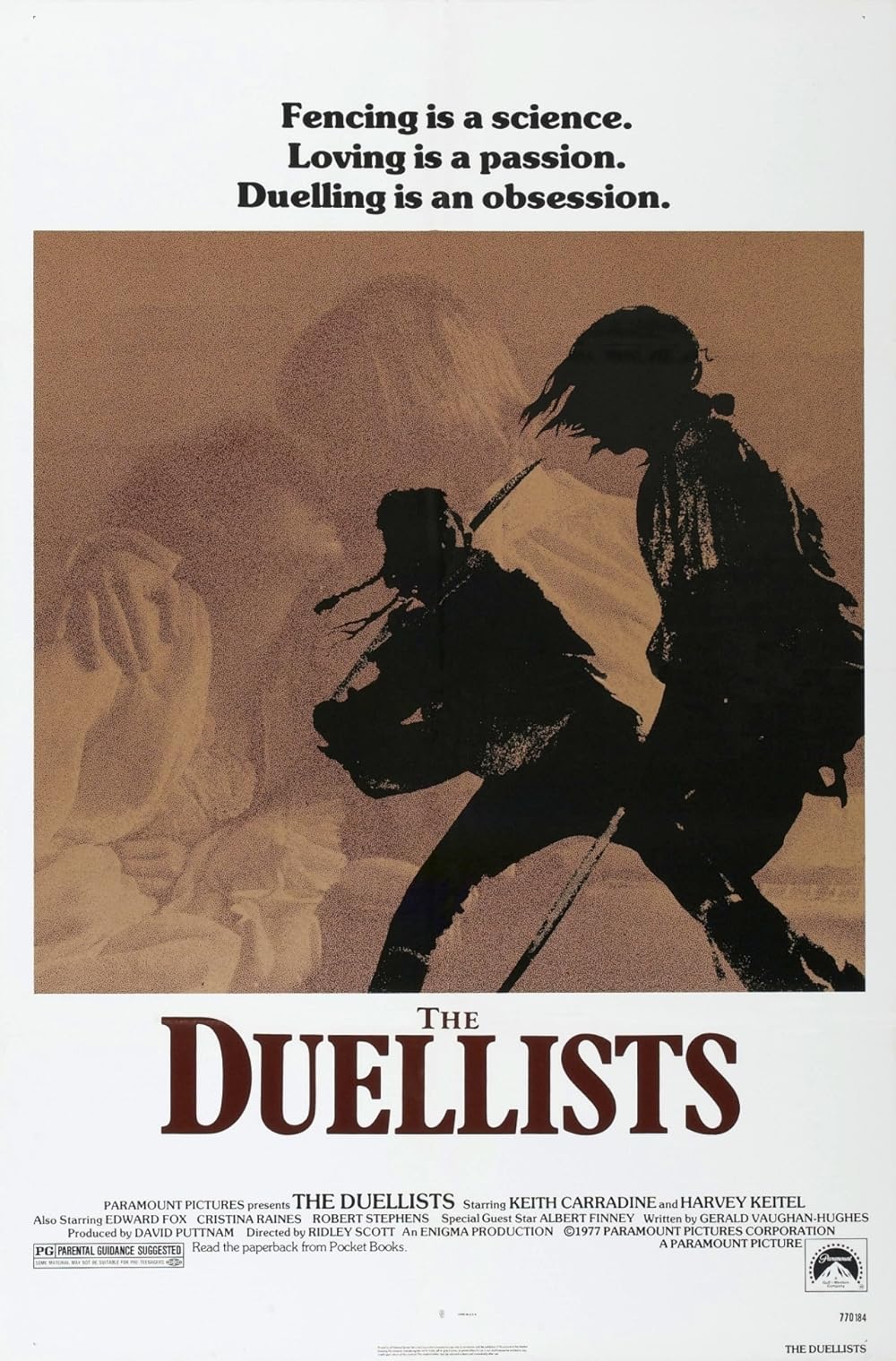

The Duellists

By Brian Eggert |

In the last scene of The Duellists, Feraud stands on a bluff and looks over a vast French landscape; the image recalls the 1830 picture of Napoleon by British painter Benjamin Robert Haydon. Feraud has just lost his last duel with D’Hubert, and as a point of honor, he can never duel with his opponent again. Over 15 years, Feraud, a soldier and former peasant who achieved some rank in Napoleon’s army, has fought D’Hubert in a series of duels. Feraud might seem to behave like a wild animal who fights for any reason whatsoever, and for whom dueling has become a “pastime,” but his drives are not that of an animal. He fights out of stubborn pride in his class—to prove himself to an enduring adversary of noble stock. Now, finally, he has lost to D’Hubert in such a way that he cannot recover. Like Napoleon, Feraud’s revolution is over; his peasant class remains somehow tragically unworthy in the end. As he stands in reflection, the Sun peers out from behind a blanket of clouds, radiating beams of light. This moment conjures history, visual brilliance, and the tragedy of the film’s narrative all in a single image. And yet this fortuitous piece of filmmaking was completely improvised by its director.

The Duellists is the first film by Ridley Scott, and it demonstrates what a supreme visualist can achieve even if limited to a shoestring budget. What he accomplishes is an astoundingly beautiful motion picture and a supremely confident piece of filmmaking. Barely distributed in America upon its 1977 release and subsequently discovered by cineastes abound after earning his rank among the greats, Scott’s intimate yet visually majestic picture, made for virtually pennies, looks and feels comparable to Stanley Kubrick’s sweeping and expensive Barry Lyndon (1975)—an obvious influence to both Scott and screenwriter Gerald Vaughan-Hughes. Made for about one-tenth the budget of Kubrick’s project, Scott’s picture embodies a kind of minimalism that takes natural wonders and makes them seem like elaborately constructed sets. In reality, scouting of actual locations and structures, and a meticulously detailed pre-production, ensured this low-budget Napoleonic Era piece stretched every dollar. Scott’s efforts are so convincing that the façade rarely shows signs of his budget’s limitations, while his command of the narrative’s themes of obsession and class conflicts are carefully balanced alongside his production’s visual luster and historical precision.

Before making celebrated classics like Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), or even this little-seen period piece for Paramount Pictures, Scott already had much technical experience and confidence behind the camera. After graduating from both the West Hartlepool College of Art and Royal College of Art, where he made his first short film (Boy and Bicycle, 1962) as a photography student, Scott became a set designer and briefly a director for the BBC. In 1968, Scott founded his advertising and commercial company Ridley Scott Associates (RSA) along with his late brother Tony, and together they flourished, making hundreds of commercials over the next few years. At the same time, Scott wanted to make his first feature film, and several unrealized projects were explored, including a heist vehicle for Michael York entitled “Running in Place,” and a Medieval horror-themed project called “Castle X.” Only when Scott began collaborating with writer Vaughan-Hughes did a film develop. Their initial idea was “The Gunpowder Plot,” a film about Guy Fawkes’ scheme to blow up Parliament in 1605. But Scott soon became interested in a Joseph Conrad short story that was based on two actual French Hussar officers, Pierre Dupont and François Fournier-Sarlovèze, and their upwards of 30 duels over 20 years, starting in 1794. Conrad’s story, called The Duel or sometimes A Point of Honor, fictionalized the real-life figures through his Lieutenants D’Hubert and Feraud.

Before making celebrated classics like Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), or even this little-seen period piece for Paramount Pictures, Scott already had much technical experience and confidence behind the camera. After graduating from both the West Hartlepool College of Art and Royal College of Art, where he made his first short film (Boy and Bicycle, 1962) as a photography student, Scott became a set designer and briefly a director for the BBC. In 1968, Scott founded his advertising and commercial company Ridley Scott Associates (RSA) along with his late brother Tony, and together they flourished, making hundreds of commercials over the next few years. At the same time, Scott wanted to make his first feature film, and several unrealized projects were explored, including a heist vehicle for Michael York entitled “Running in Place,” and a Medieval horror-themed project called “Castle X.” Only when Scott began collaborating with writer Vaughan-Hughes did a film develop. Their initial idea was “The Gunpowder Plot,” a film about Guy Fawkes’ scheme to blow up Parliament in 1605. But Scott soon became interested in a Joseph Conrad short story that was based on two actual French Hussar officers, Pierre Dupont and François Fournier-Sarlovèze, and their upwards of 30 duels over 20 years, starting in 1794. Conrad’s story, called The Duel or sometimes A Point of Honor, fictionalized the real-life figures through his Lieutenants D’Hubert and Feraud.

The film opens in Strasbourg in 1800 and lasts through the Napoleonic Wars, ending in Tours in 1814. When Feraud (Harvey Keitel) wounds the mayor’s nephew in a duel, the Brigadier-General orders D’Hubert (Keith Carradine) to place Feraud under house arrest, which Feraud takes as a personal insult from D’Hubert. He challenges his fellow Lieutenant to a duel with sabers, and both men survive after D’Hubert strikes a blow to Feraud’s arm that prevents his opponent from continuing. Feraud’s wild rancor returns in a series of chance encounters over the years, and their ongoing conflict earns a fabled reputation throughout the ranks. Their enduring quarrel is called “fighting on parade,” and in Lubeck, it’s greeted by a breakfast party, like an audience seated in bleachers for the show. But years pass, and history “rolls over” their reasons. Friends suggest the two were enemies in a previous life, and their “quarrel obscura” has been predestined. Each man keeps going out of honor, which reaches almost absurd levels. Consider the duel where D’Hubert raises his hand to pause, turns to sneeze, and then returns to the duel. The kind of etiquette that allows for sneezing but no sense of understanding or forgiveness between soldiers becomes one of the film’s great ironies.

D’Hubert would seem to be the film’s hero, pestered by Feraud’s relentless demand for satisfaction. His personal life is offset by his obligation to duel when his mistress Laura (Diana Quick) leaves him by writing “goodbye” on his saber in red lip rouge. Often reluctant to fight but compelled by honor to do so, D’Hubert makes attempts to reconcile his conflict with Feraud, offering apologies, a friendly drink of Schnapps, and even a pardon to satisfy his enemy, all of which are rejected courtesies. Feraud’s ceaseless pride matches that of Napoleon’s lust for power, in that his frantic need to prove himself and his peasant class as the equal of, if not better than D’Hubert’s nobility, ultimately leads to overzealous self-destruction. Most poetic is how The Duellists does not require one of these characters to die by the hand of the other. In time, Napoleon is defeated, and his loyalists are branded criminals. Feraud would be executed if D’Hubert did not use his enduring influence to earn his opponent clemency; nevertheless, Feraud still demands satisfaction. During the final duel with pistols on D’Hubert’s estate, amid stunning ruins Scott found in the French countryside, D’Hubert has the opportunity to finally kill Feraud and instead declares their quarrel has ended. Much like Napoleon after Waterloo, Feraud is left alive either to dwindle like his former ruler or, as the sunlight emerging from behind the clouds suggests, accept his defeat and move on as France has done.

Scott secured a mere $900,000 budget after bringing the project to British producer David Puttnam, who agreed to produce the film at Paramount. The director originally wanted Michael York and Oliver Reed to star as D’Hubert and Feraud, but their salaries proved too expensive; among the affordable actors were Carradine and Keitel, both of whom took convincing. And Scott was forced to delay shooting while Carradine finished a musical tour for his Oscar-winning hit “I’m Easy,” the song Carradine wrote for Robert Altman’s film Nashville (1975). Keitel was coaxed by Scott, who told the actor that shooting in France would be tantamount to a vacation of extravagant wine and cigars. Filming lasted just over two months in France, England, and Scotland, and Scott used only existing structures and interiors; his meager budget wouldn’t allow for set construction. In total, Scott had no more than a few dozen extras at his disposal, and yet in every frame, his use of clever angles and blocking hide his budgetary constraints. As suggested earlier, with the final shot of the Sun peeking from behind the clouds, Scott’s production was graced with unexpected moments where the camera captured Nature performing. Take the scene where D’Hubert proposes to his future wife Adele (Cristina Raine, Carradine’s then-lover). Raines’ horse was in heat, and so we see both horses “flirt” with one another as the actors try to perform their lines. Raines giggles throughout the proposal as the horses touch noses, and Carradine cracks a smile. Offscreen, the erection on Carradine’s horse caused Raines to break character, but onscreen, the moment seems like an authentic touch of romance between two people who have just fallen in love.

Most memorable is the film’s series of duels, orchestrated by Bill Hobbs and shot with a diversity of styles by its director. A blend of handheld camerawork and tripod shots both place the viewer in the action and establish the formality of the dueling ritual. Violent, clanging swordplay performed with steel blades is jarringly real, as the actors carried out these scenes not with artificial weapons but with blunted edges on actual swords and no button to dull the point. Hobbs’ choreography ensured the actors didn’t kill each other, but the very real threat of death in a possible accident enhanced both central performances. Carradine was versed in fencing, but Keitel had never held a sword; as a result, the intense Mean Streets (1973) actor often lost himself in the moment and stepped outside of his marks, forcing Carradine to improvise his swordplay within the scene if only out of self-preservation. Hobbs’ attention to detail and historical research into the art of dueling offers battles that look unlike any other screen duels, with actors wearing the period’s long braids of hair down their cheeks to protect their faces from their opponent’s blade. D’Hubert and Feraud occupy stances authentic to the period, but to viewers accustomed to typical movie duels that use a more rigid formal posture, the bending martial arts poses held by Carradine and Keitel may look strange. Consequently, each distinct duel is more fascinating than the last.

Of course, one cannot avoid comparing his film to Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, released two years earlier, given Scott’s visual treatment throughout and the narrative structure. Both pictures are set on similar landscapes and recounted by a British-voiced narrator who seems to regard the material from a third-party historical perspective, though the narrator of Scott’s film has a less intrusive and manipulative modus operandi than Kubrick’s. Howard Blake’s original score for The Duellists is a persistent, winding, haunting, and melancholy theme that recalls Kubrick’s composer Leonard Rosenman’s use of Handel’s similar piece, “Sarabande.” The opening shot of Kubrick’s film is a gun duel. Scott’s opening shot also leads us to a duel, following a young girl and her gaggle of geese into a master shot of Feraud and his opponent, an image framed much the same as Kubrick’s. Frank Tidy, Scott’s longtime cinematographer on hundreds of commercials for RSA, uses natural lighting, often relying on an open window for Vermeer-esque luminosity or candlelight to provide a glowing light source, the same sort of approach that won Kubrick’s cinematographer John Alcott the Oscar. Much like Alcott’s work, Tidy’s compositions are painterly and vast; on a few occasions, he even uses the same technique employed by Kubrick throughout Barry Lyndon: the frame begins tight on an isolated and intimate subject, often comparable to a still life, but then pulls back for a larger view. Scott even uses actress Gay Hamilton as Feraud’s mistress, the actress who played Barry’s first love and cousin in Kubrick’s film.

Despite the similarities to Barry Lyndon, which should be considered inspired homage versus artistic pilfering, The Duellists is a ceaselessly gorgeous motion picture that nonetheless bears Scott’s personal touch. From the meticulously researched costumes by Tom Rand and production design by Peter J. Hampton, Scott’s film has many of the same qualities that made his later historical epics, such as Gladiator (2000), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), and Robin Hood (2010) so exceptional. Far different from Kubrick is the director’s use of short bursts in editing, also used later in Alien and other actionized Scott projects. Most of his first film is shot with long takes, each shot carefully pre-planned with storyboards, allowing for very little improvisation in terms of his shot list. For one sequence, however, Scott breaks this method to enhance the emotional experience for the viewer. During the duel on horseback, D’Hubert believes he may finally die. Scott interrupts the action with shots of Laura warning him of his impending death and Feraud’s lunging battle cry “la!” The staccato montage shows D’Hubert’s life flashing before his eyes as he rides his horse into the duel, and by chance, he prevails, striking a caustic blow to Feraud’s head, a bloody image seen for a fraction of a second. Scott’s vision earned his picture two BAFTA nominations for Cinematography and Costume Design, as well as a nomination for the Palme d’Or and a win for the Caméra d’Or (best first film) at the Cannes Film Festival.

Despite the similarities to Barry Lyndon, which should be considered inspired homage versus artistic pilfering, The Duellists is a ceaselessly gorgeous motion picture that nonetheless bears Scott’s personal touch. From the meticulously researched costumes by Tom Rand and production design by Peter J. Hampton, Scott’s film has many of the same qualities that made his later historical epics, such as Gladiator (2000), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), and Robin Hood (2010) so exceptional. Far different from Kubrick is the director’s use of short bursts in editing, also used later in Alien and other actionized Scott projects. Most of his first film is shot with long takes, each shot carefully pre-planned with storyboards, allowing for very little improvisation in terms of his shot list. For one sequence, however, Scott breaks this method to enhance the emotional experience for the viewer. During the duel on horseback, D’Hubert believes he may finally die. Scott interrupts the action with shots of Laura warning him of his impending death and Feraud’s lunging battle cry “la!” The staccato montage shows D’Hubert’s life flashing before his eyes as he rides his horse into the duel, and by chance, he prevails, striking a caustic blow to Feraud’s head, a bloody image seen for a fraction of a second. Scott’s vision earned his picture two BAFTA nominations for Cinematography and Costume Design, as well as a nomination for the Palme d’Or and a win for the Caméra d’Or (best first film) at the Cannes Film Festival.

Having a background in commercials or music videos has become something of a standard for young filmmakers to break into features, though few of today’s directors exhibit the level of craftsmanship and artistry Ridley Scott did with his first film. With hundreds of commercials to his name by the time he made The Duellists, his experience and control of the medium were vast and have only grown into mastery in the years since. This is an astonishingly assured motion picture that foretells a magnificent career in commercial cinema, where he makes films that, though occasionally their stories may sometimes be hit or miss, always have something interesting onscreen. In cases like this one, and several more in the 35 years since its release, Scott has proven himself a genius-level visualist and a superb storyteller whose best works often take us far into humanity’s future or deep into our past. With The Duellists, his look at this Napoleon-era setting represents a wholly unique story for the period on film, and an unconventional treatment of the honor-bound conflict between two men. That it is perhaps Scott’s most underseen film is one of cinema history’s little tragedies, as it certainly ranks among his very best.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review