The Double

By Brian Eggert |

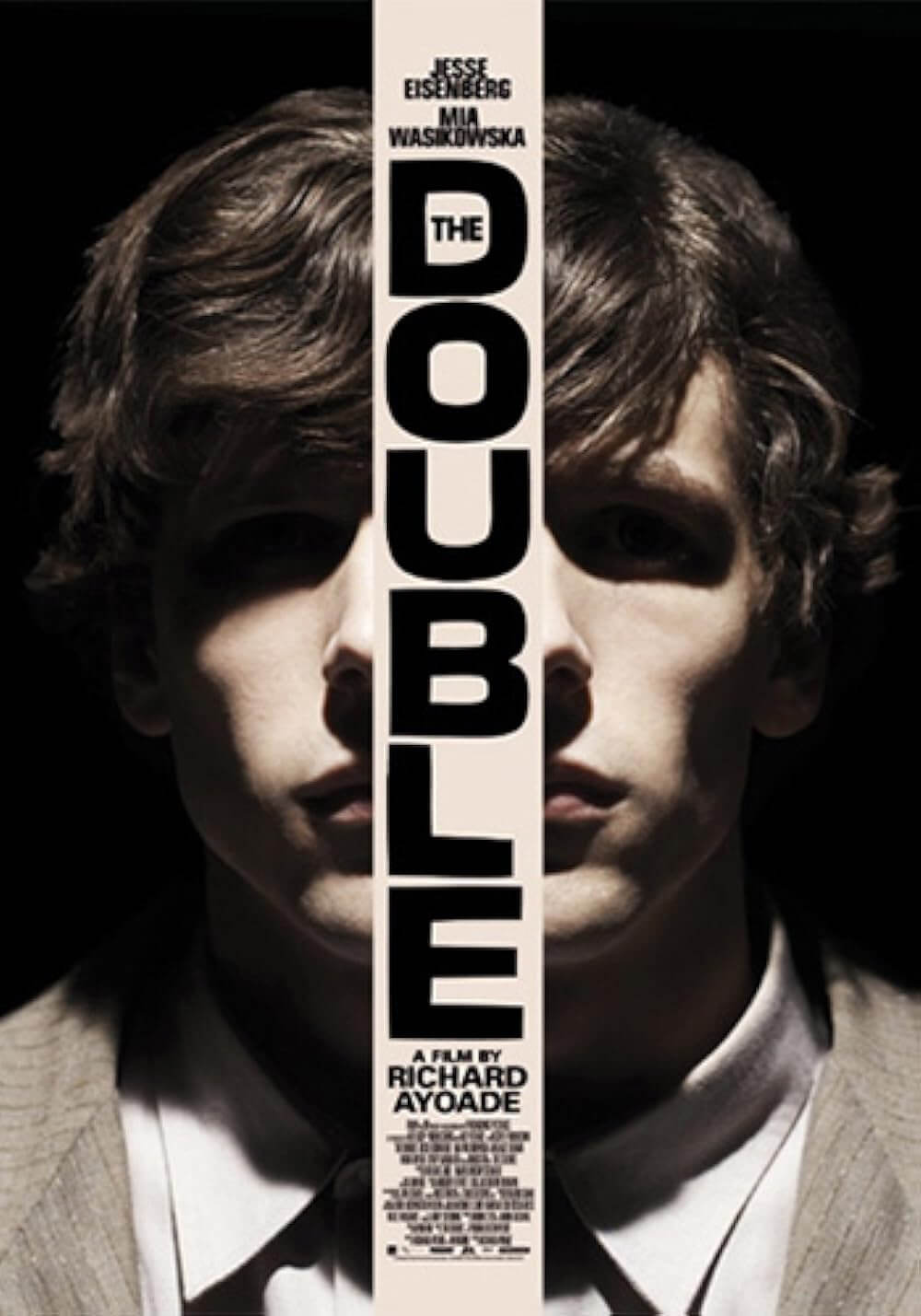

Though at times overwhelmed by its own influences, Richard Ayoade’s second feature, The Double, nonetheless proves itself an inspired amalgamation of some very brainy motion pictures, offering an introspective nightmare-comedy saturated in arthouse stylization. Ayoade, the British actor from The IT Crowd and now sophomore filmmaker, who debuted his considerable talents on his outstanding coming-of-age comedy Submarine in 2010, demonstrates his extensive artistic scope in this tale of paranoia and social anxiety. Inspired by the great Fyodor Dostoyevsky novella (a personal favorite of this critic), Ayoade’s film has more in common with Orson Welles’ version of Kafka’s The Trial, or Terry Gilliam’s Brazil—and about a dozen other analogous sources from literary and film history—complete with pervading senses of helplessness and inescapability in a claustrophobic, pseudo-modern bureaucracy. Rather than a faithful modernization of Dostoyevsky, the source material is a springboard for this creative young director to engage in some very ambitious, very intellectual filmmaking.

From the film’s first moments, it becomes readily apparent that at least part of this picture exists in the headspace of its protagonist, lowly office worker Simon James (Jesse Eisenberg). Even so, David Crank’s deceptively minimal production design creates a world that looks like the 1940s’ view of a not-too-distant dystopian future, where cumbersome technology, exposed wires, massive copy machines, and tiny living spaces hum along in dim amber-toned light. Drab yet filled with fascinating details, the setting is also enlivened by what’s apparently permanent nighttime and a rich helping of high-contrast shadows thanks to the stark overhead lighting by cinematographer Erik Alexander. This industrial space is made even more surreal by Andrew Hewitt’s score, which in one sequence finds a tempo inside a computer clicking (indeed, the nods to Brazil are unsubtle); elsewhere, the aural presentation feels ripped from the oeuvre of David Lynch with the sound of machinery dissonance, and elsewhere still Hewitt’s music booms with a hugely dramatic orchestra.

Simon is a “non-person” who toils for a company that does who-knows-what involving cubicles and cramped workspaces. His fast-talking, fast-moving boss (Wallace Shawn) doesn’t even recognize him, despite Simon having worked there for 7 years. Even the security guard to his building (Kobna Holdbrook-Smith) requires him to show his ID each day, a look of suspicion on his face as if they’ve never met, while other employees enter with a friendly nod of recognition. And those who do acknowledge Simon, for example his mother (Phyllis Somerville), do so with indifference if not outright contempt. But all Simon cares about is getting the attention of Hannah (Mia Wasikowska), the coworker and neighbor across the way to whom he cannot form the courage to speak and on whom he spies with a telescope. His miserable existence becomes even worse when Simon’s doppelganger, named James Simon (also Eisenberg), arrives at the office and proves to be everything he’s not—confident, popular with women, successful in his work, and quit witted. Although they’re virtual facsimiles, no one sees the similarities between the two because they’ve never really looked at Simon.

Simon and James are the only ones who realize they look exactly alike, and at first the more confident James agrees to help his weedier counterpart get together with Hannah (in a Cyrano de Bergerac strain) in exchange for Simon’s help at the office. Their amiable, if stressful, collaboration ends quickly after Hannah confesses she’s fallen for James, while James blackmails Simon for all manner of seedy exploits involving the use of Simon’s apartment. There’s an ever-present tension that escalates from start to finish in The Double, making it a kind of paranoid thriller that borrows elements from Alfred Hitchcock (specifically Rear Window) and Fritz Lang (namely M). But there are also deftly comic sequences, such as the momentary glances into this world’s television—Simon’s favorite show being a cornball sci-fi adventure starring a laser-wielding hero (Paddy Considine, hilarious). And there are countless obscure and deadpan responses from unbending administrative types who Simon runs into along the way. In one scene, Sally Hawkins refuses Simon’s entry into the company ball and asks him, “Do you think you know me?” To this, he’s as confused as we are, except he’s not laughing.

One of the joys of The Double is watching how magnificently Eisenberg embodies two very different personalities through body language, vocalized pauses or lack thereof, and simple expressions. Eisenberg’s heavy brow and mopish hair supply his character with optimal shadows to enhance the character’s distorted perceptions and our perceptions of him, whichever version it may be. Wasikowska, rather lovely in a small way, is also a delight as a complicated character. But how this unease-ridden scenario plays out may mystify some as to its meaning, and brings into question the film’s debatable balance between its unyielding style and the emotional resonance of the story. Certainly, it’s easy to feel consumed by Ayoade’s hyper-stylization and effective use of a million influences ranging from Welles to Gilliam, and also from Jean-Luc Godard to Aki Kaurismaki. Perhaps, like the filmmakers he wishes to emulate, it takes more than one viewing to take in everything in The Double’s inundating visual and aural presentation.

Overcome by a routine of maddening hindrances to keep Simon wrapped up in the bureaucratic nightmare, The Double is stressful viewing, full of exhausting repetition and feelings of alienation throughout. The audience is put through the wringer along with Simon, thrust into a miserable world that’s never quite as downright frightening as Welles’ The Trial or Gilliam’s Brazil, but its dystopian trademarks are firmly established and wear on us during the short-but-feels-longer 90-minute runtime. However, these feelings are all very intentionally placed by their director, and that’s the film’s minor genius. Ayoade has carefully considered his subject and influences, and he’s used them in a discerning manner to create a picture that, while an offshoot, never feels plagiaristic. For a second film, The Double is a huge leap forward from Submarine both thematically and stylistically, and establishes Ayoade as a serious and unique filmmaker who’s taking comedy into a film-savvy realm not explored since the arrival of Wes Anderson. Here’s hoping Ayoade’s career is on the same trajectory.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review