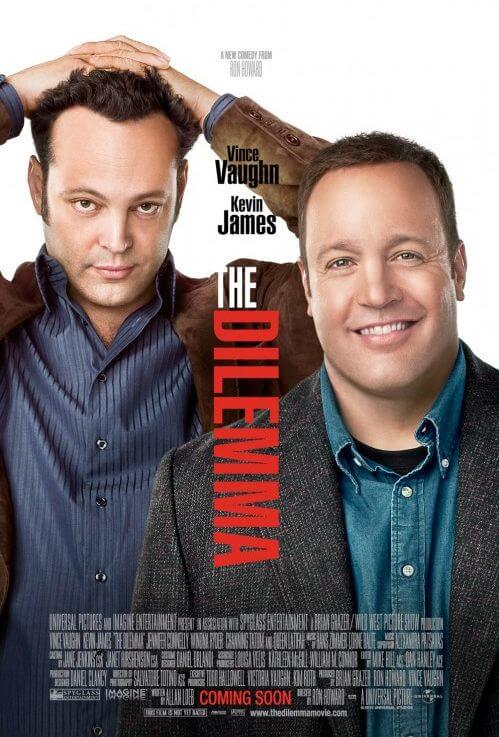

The Dilemma

By Brian Eggert |

Vince Vaughn and Kevin James star in The Dilemma, a “bromance” seemingly written with their respective typecast characters in mind. Vaughn’s fast-talking, overconfident guy’s guy comes equipped with equal parts dirty-mindedness and sentimentality; it’s the same performance Vaughn gave in Wedding Crashers and many other titles. James (Grown Ups) has only one character; he fills the quota for a “husky” and loveable best friend type, sorta pathetic but with plenty of personality. Together, they man-hug and declare their best friendship, playing roles that for them are so cliché they seem like impersonations.

Vaughn and James are Ronny and Nick, best friends and co-founders of a specialty engine shop in Chicago, with Ronny using his skills as a loudmouth to sell Nick’s designs. Ronny dates Beth (Jennifer Connelly), a successful chef who was patient as he overcame his gambling addiction. Nick is married to Geneva (Winona Ryder), his college sweetheart. Both men look physically oversized to their respective mates, Vaughn’s massive head making Connelly look like a twelve-year-old by comparison, and James at risk of crushing Ryder’s petite frame. Anyway, Ronny and Nick are about to close a major deal with Chrysler to design a special electric engine for muscle cars. In the midst of their planning, Ronny spies Nick’s wife locking lips with another man. As the film’s advertising asks, how does a man tell his best friend that his wife is cheating?

But before such questions are answered, there are things to consider. Ronny and Nick have to make good on the “Big Deal” with Chrysler, which comes into jeopardy if Nick is too stressed about his marriage to think about designing an engine. And when Ronny confronts Geneva, she threatens to lie and say that Ronny made a pass at her; after all, they have a secret history from before she and Nick fell in love. You can bet Ronny attempts to get photographic proof of the affair with wacky results. And you shouldn’t forget about Ronny’s former gambling problem, because that causes a whole slew of misunderstandings. What the story amounts to is an episode of a bad sitcom dragged out into a feature film, except messier. Everyone involved can do better. I wish they would have.

Curiously, Ron Howard directed the film, stepping down from his A-list throne for a low-grade relationship comedy between award-hungry projects. He reverts to a style not implemented since the early part of his career, with titles like Splash and later EdTV. And just when Cinderella Man and Frost/Nixon showed so much promise. He’s a hit-or-miss filmmaker with more misses than hits, and with any luck, The Dilemma will send moviegoers perusing Howard’s filmography, where they’ll find a list of disappointments directed without much personal style to speak of. Howard’s overrated stature has gone on long enough; the film community’s love of his work remains inexplicable, at least from a critical point of view. But this is a minority opinion, as America seems to love bland filmmaking more and more.

There’s plenty bland about the screenplay by Alan Loeb, writer of The Switch and Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. Loeb keeps the majority of characters and their relationship troubles feeling real; this is most true with Geneva’s conniving duplicity, which Ryder plays to effective degrees of despicable. Vaughn, playing to expectations, deviates from the script for a number of his trademarked rants (there’s an excruciating speech at a wedding anniversary party that will have you cringing from its social faux pas). The most baffling aspect of the story, however, must be co-adulterer Zip, played by “hunk” Channing Tatum. The tattooed punk shows up among these comparatively “normal” people with his drugs and guns and makes us wonder, Why is he in this movie? There’s no reasonable explanation for why Tatum’s character is such an oddball, except maybe the filmmakers thought everyone else was too predictable. They would be right.

You might also wonder what Oscar-winners Connelly and Queen Latifa are doing in The Dilemma. Connelly doesn’t do much at all except play the at-first-suspicious-then-later apologetic-but-“always there” girlfriend. Latifa has a token role as Ronny and Nick’s filthy-mouthed contact at Chrysler (buy Chrysler cars, by the way—the movie wants you too, so bad) and embarrasses herself in the process. Everyone seems miscast in a movie that could work, perhaps even well, if the director knew where to trim the fat. Loeb’s script occasionally touches a chord, but at two hours, Howard’s refusal to delete even one pointless subplot (there are many) taxes the viewer after the third or fourth change in tone. When it’s all over, the viewer has trouble making sense of why some scenes were included or how the dilemma was resolved. Question is, does it matter?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review