Reader's Choice

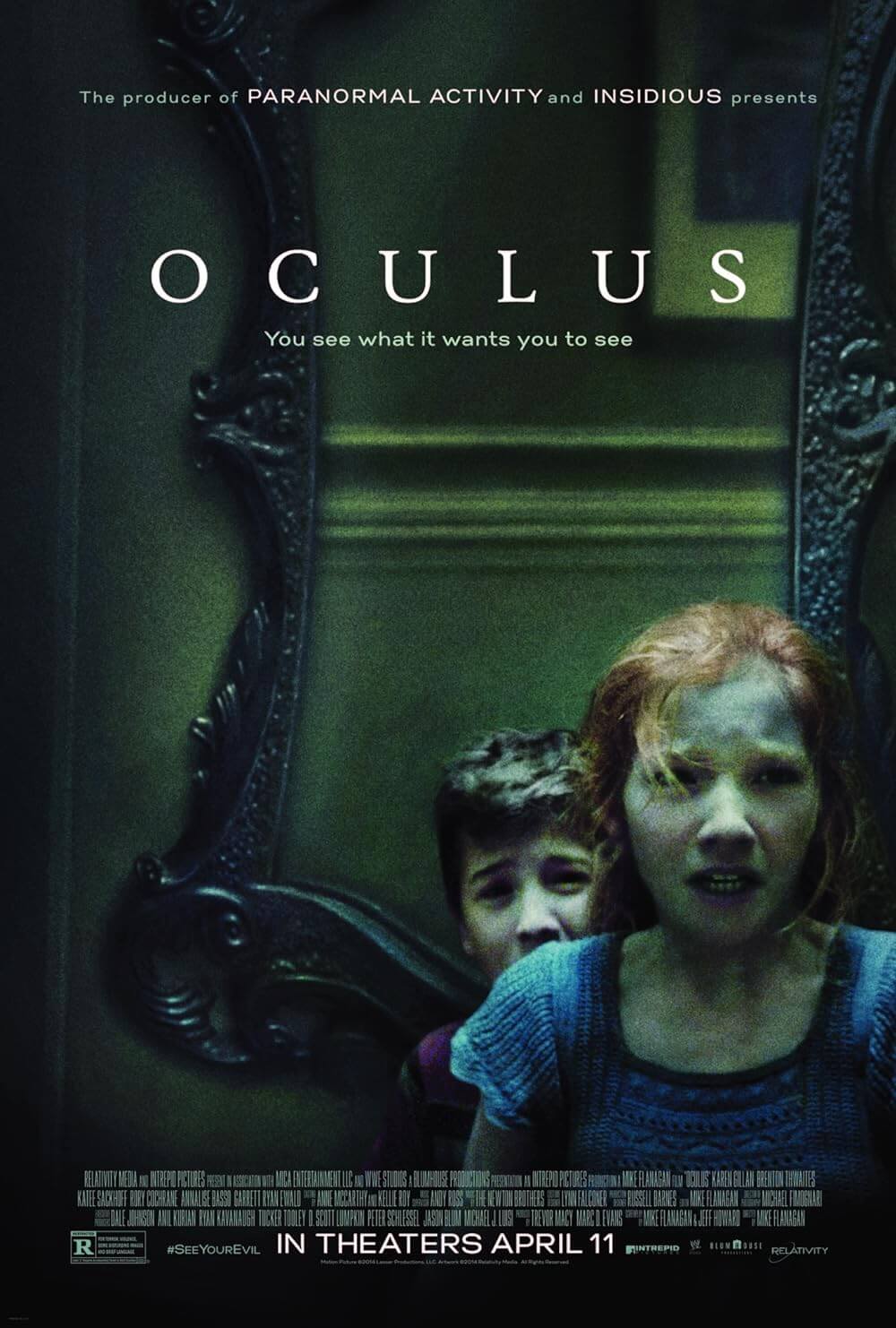

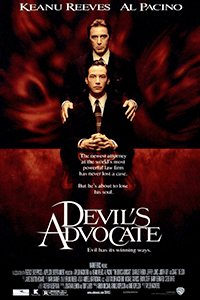

The Devil’s Advocate

By Brian Eggert |

The Devil’s Advocate is a seductive, Faustian tale of temptation and vanity masquerading as a legal thriller. Keanu Reeves plays Kevin Lomax, a defense attorney from Gainesville, Florida, where, in the opening scene, he defends a pedophile whom he knows to be guilty because he wants to win the case. For Kevin, a flawless win rate is more important than everything else—his morality, his wife, even his eternal soul. But he doesn’t know this about himself yet. Directed by Taylor Hackford, the film tells the story of the naive but talented attorney who’s talked into uprooting his life and moving to the Big Apple, where he serves under the resident Mephistopheles. More accurately, Kevin is tempted by the head of an all-powerful law firm, winkingly named John Milton (as in the author of Paradise Lost, 1667) and played by Al Pacino. Milton later announces, “I have so many names,” with a playful inflection, emphasizing what the title already reveals. Although Pacino’s wily and delicious performance eventually leads to an over-the-top climax that threatens to derail the entire picture, The Devil’s Advocate develops patiently and effectively over 143 minutes. Given its concern with the gradual degradation of well-drawn characters in the preceding two hours, the late-film silliness is forgivable.

Hackford’s project arrived in 1997 amid Hollywood’s obsession with John Grisham fiction. The bestselling novelist’s first major success, The Firm, was adapted in 1993 by Sidney Pollack, starred Tom Cruise and Gene Hackman, and became a major box-office hit over the summer. Later that year, Alan J. Pakula directed The Pelican Brief with Julia Roberts and Denzel Washington as the leads, resulting in another smash. In the subsequent years, several top-tier directors commanded all-star casts in various other Grisham adaptations, and most of them performed extraordinarily well in financial terms: Joel Schumacher directed Susan Sarandon and Tommy Lee Jones in The Client (1994), following that up with A Time to Kill (1996), featuring Sandra Bullock, Samuel L. Jackson, and Matthew McConaughey. James Foley helmed The Chamber (1996), starring Chris O’Donnell and Hackman, delivering the sole critical and commercial loser in the bunch. And a month after The Devil’s Advocate hit theaters, Francis Ford Coppola released The Rainmaker, featuring a breakout performance from Matt Damon one month before Good Will Hunting arrived in theaters.

Given the compressed timeframe of these films and Grisham’s ubiquity in 1990s popular culture, the author’s influence on The Devil’s Advocate cannot be overstated. Based on a 1990 novel by Andrew Neiderman, his biggest success, the screenplay was adapted by Jonathan Lemkin for Joel Schumacher to direct. The project under Schumacher stalled. only to be picked up by Hackford, who oversaw a rewrite by his Dolores Claiborne (1995) screenwriter Tony Gilroy. Given the omnipresence of legal thrillers and their proven track record for big business, the project warranted a $57 million budget from Warner Bros., the studio behind The Pelican Brief, The Client, and A Time to Kill. Each had earned over $100 million in global box-office receipts, making legal thrillers a proven commodity—at least, until audiences lost interest after Robert Altman’s underrated The Gingerbread Man (1998) bombed and Gary Fleder’s Runaway Jury (2003) underperformed. But Hackford’s project seemed like a clear winner, especially after casting the bankable Pacino and Reeves. Indeed, the film broke even domestically but earned a profit with its international take.

Given the compressed timeframe of these films and Grisham’s ubiquity in 1990s popular culture, the author’s influence on The Devil’s Advocate cannot be overstated. Based on a 1990 novel by Andrew Neiderman, his biggest success, the screenplay was adapted by Jonathan Lemkin for Joel Schumacher to direct. The project under Schumacher stalled. only to be picked up by Hackford, who oversaw a rewrite by his Dolores Claiborne (1995) screenwriter Tony Gilroy. Given the omnipresence of legal thrillers and their proven track record for big business, the project warranted a $57 million budget from Warner Bros., the studio behind The Pelican Brief, The Client, and A Time to Kill. Each had earned over $100 million in global box-office receipts, making legal thrillers a proven commodity—at least, until audiences lost interest after Robert Altman’s underrated The Gingerbread Man (1998) bombed and Gary Fleder’s Runaway Jury (2003) underperformed. But Hackford’s project seemed like a clear winner, especially after casting the bankable Pacino and Reeves. Indeed, the film broke even domestically but earned a profit with its international take.

The Grisham mode is evident from the outset of The Devil’s Advocate, complete with a promising young lawyer from humble Southern roots taking a corruptive job with a high-powered, big-city practice, only to discover they’re into some shady dealings. The Firm establishes this narrative trajectory exactly, with Cruise’s recent Harvard graduate from Tennessee wooed by a conniving Hackman; he moves to Chicago with his wife, only to be tempted by a seductress before learning of the firm’s amorality. The difference between the two narratives is the religious and stark moral underpinnings in Hackford’s film, which finds Kevin and his wife Mary Ann (Charlize Theron) moving from Gainesville to New York, a fiery sexpot attorney Christabella (Connie Nielsen) tempting Kevin, and both being exploited by none other than Old Scratch himself. If the setup is familiar, the texture of the storytelling enriches the material, with the terrific headlining cast giving committed performances that sell the increasingly ridiculous events. All the while, Hackford enjoys alluding to but not altogether revealing Milton’s identity as Satan, while the audience remains several steps ahead in discovering this. Whether it’s Pacino’s yellow teeth, rotten nails, increasingly unhinged hair, or the way he seems to be smoking in one scene as though his body is blazing hot—the hints are not subtle. To be sure, the original trailers spoil the twist, and the viewer waits for Kevin to catch up.

The story unfolds as Milton seduces Kevin, who has been thoroughly warned about the temptations of Babylon by his Bible-thumping mother (Judith Ivey). Kevin undergoes a series of trials—legal tests arranged by Milton. The first involves a case of animal sacrifice by a cultist (Delroy Lindo), whom Kevin defends on the basis of religious freedom. The next case entails a high-profile triple-murder involving an accused land developer, the well-connected Cullen (Craig T. Nelson). While Kevin acclimates himself to Milton’s firm, Mary Ann has trouble settling into their lavish new apartment in a veritable Tower of Babel, where Milton occupies the penthouse. She busies herself with plans for starting a family, the apartment’s décor, and paint colors. But she can’t seem to find the right green. One of them is too “institutional,” according to Jackie (Tamara Tunie), one of the vapid firm wives. Over the ensuing weeks, Mary Ann slowly loses her mind after seeing demonic and disturbing hallucinations. The character seems underserved in the first half. Still, Theron’s committed performance renders Kevin’s eventual choice to have her committed—in an institution with the same green hue, no less—as tragic. Reeves’ performance when Mary Ann kills herself in the hospital is also quite convincing.

The production spared no expense, evidenced by pricey on-location shooting in New York, including a scene where the production shut down several blocks to film Reeves alone on 57th Street, the vacant road extending to the horizon, capturing Kevin’s isolation. Familiar locations throughout the city appear, often shot with bizarre angles and sped-up photography to give them an uncanny appearance. But the interiors prove just as otherworldly. Bruno Rubeo’s sublime production design conceives Milton’s apartment as though the devil were Gordon Gekko, including a vast fireplace, a walk-out balcony with a pool and no railing, and a wall sculpture resembling either heavenly clouds or the detached wings of a fallen angel. With some historical irony, the production cast Donald Trump’s golden penthouse from Trump Tower as the home of the duplicitous Cullen, the high-powered liar, pedophile, and murderer who has Satan in his corner. Throughout the production, Andrzej Bartkowiak’s cinematography captures the proceedings in rich, painterly colors that hint at the vast Biblical stakes between good and evil.

The production spared no expense, evidenced by pricey on-location shooting in New York, including a scene where the production shut down several blocks to film Reeves alone on 57th Street, the vacant road extending to the horizon, capturing Kevin’s isolation. Familiar locations throughout the city appear, often shot with bizarre angles and sped-up photography to give them an uncanny appearance. But the interiors prove just as otherworldly. Bruno Rubeo’s sublime production design conceives Milton’s apartment as though the devil were Gordon Gekko, including a vast fireplace, a walk-out balcony with a pool and no railing, and a wall sculpture resembling either heavenly clouds or the detached wings of a fallen angel. With some historical irony, the production cast Donald Trump’s golden penthouse from Trump Tower as the home of the duplicitous Cullen, the high-powered liar, pedophile, and murderer who has Satan in his corner. Throughout the production, Andrzej Bartkowiak’s cinematography captures the proceedings in rich, painterly colors that hint at the vast Biblical stakes between good and evil.

Where the film falls—and falls hard—are the last twenty or so minutes. While the story builds gradually for two hours, the final sequence, where Milton reveals himself not only as Satan but Kevin’s father, plays out in a hackneyed fashion. The ‘90s-era CGI used to render hellfire, contorted demon faces (designed by Rick Baker, no less), and Milton’s tortured soul sculptures with copulating figures looked laughable in 1997 and has aged even worse. Moreover, Pacino’s mischievous presence earlier in the movie gives way to an insidious but tongue-in-cheek figure who, in the last moments, breaks the Fourth Wall and remarks to the viewer about his favorite sin—vanity. This isn’t the only time Hackford has Milton break from the drama to confront the viewer. Note an earlier sequence featuring Milton in church, attending the funeral of a firm executive (Jeffrey Jones) whom he had killed. When no one’s watching but the viewer, Milton playfully holds his finger above some holy water. The camera looks down from above, taking a God’s eye view. Suddenly Milton looks into the camera with a gleeful smile, then dips his finger, prompting the water to boil at his touch.

Pacino’s hamminess when Milton goes full-devil spoils the dramatic integrity of The Devil’s Advocate. Though later scenes where Milton gives grand speeches about God being “a sadist” and “absentee landlord” prove inspired, with Pacino lending his theatrical performative style to their delivery, the plot contrivance and the computery execution leave much to be desired. Still, Pacino belongs on a list of great actors who have played Satan, including Walter Huston, Jack Nicholson, Robert DeNiro, Viggo Mortensen, Gabriel Byrne, and Tom Waits. Yet, Pacino’s performance is both the film’s clear selling point and an element that cheapens the legal drama. But much of the fault lies in the script, which resorts to a B-movie development when Milton attempts to talk Kevin into impregnating Christabella, revealed as Kevin’s half-sister and, therein, father the Antichrist. Certainly, films such as Rosemary’s Baby (1968) have successfully injected the supernatural into an otherwise grounded scenario, but Hackford mishandles the finale and indulges the concept too much. A more restrained, perhaps even entirely metaphoric, approach may have better preserved our investment in the story.

Instead, we’re left with a conclusion that feels like a cheat: Kevin resolves to commit suicide rather than sleep with his sibling and bring about the apocalypse (a good call). But after a hodgepodge of animated fire and a young, winged Satan, played by Reeves, screams into the air, Kevin wakes up back in Gainesville at the trial where he knowingly defended a pedophile. Apparently unaware that he has respawned, he resolves to do the right thing this time. In a move that could leave him disbarred, he announces in court that he will no longer represent his client, only to be tempted once again by a journalist, Milton in disguise, looking to interview Kevin about his career-destroying choice and make him a celebrity. Milton has reset the game to once more test his son. How many variations of this Faustian bargain have there been or will there be? Will they continue for eternity until Milton convinces Kevin to bed his half-sister? In the end, Hackford’s film almost appears to be on Satan’s side, indulgently watching as the cartoonish trickster proclaims he’s at it again. It’s neither dramatically satisfying nor particularly well executed.

Instead, we’re left with a conclusion that feels like a cheat: Kevin resolves to commit suicide rather than sleep with his sibling and bring about the apocalypse (a good call). But after a hodgepodge of animated fire and a young, winged Satan, played by Reeves, screams into the air, Kevin wakes up back in Gainesville at the trial where he knowingly defended a pedophile. Apparently unaware that he has respawned, he resolves to do the right thing this time. In a move that could leave him disbarred, he announces in court that he will no longer represent his client, only to be tempted once again by a journalist, Milton in disguise, looking to interview Kevin about his career-destroying choice and make him a celebrity. Milton has reset the game to once more test his son. How many variations of this Faustian bargain have there been or will there be? Will they continue for eternity until Milton convinces Kevin to bed his half-sister? In the end, Hackford’s film almost appears to be on Satan’s side, indulgently watching as the cartoonish trickster proclaims he’s at it again. It’s neither dramatically satisfying nor particularly well executed.

Even with a ham-fisted ending and some unsubtle Biblical references throughout, even with Reeves and Theron’s inconsistent Southern accents, and even with the obvious horror-inflected Grisham structure, The Devil’s Advocate works. It shouldn’t, but it does, leaving you with a sense of goodwill toward this messy movie and its remarks about elitist hedonism—ironic, coming from Hollywood. Although the whole movie might be an elaborate jab at lawyers, it’s surprisingly free of lawyer jokes (so here’s an appropriate one: What’s the difference between a lawyer and God? God doesn’t think he’s a lawyer.). Perhaps because the central conceit takes itself so seriously for much of the film, the impressive cast and Hackford’s assured direction stick the landing, regardless of its later faults. Like Grisham’s novels, Hackford and his screenwriters show the corruptive power of high-powered law firms and how lawyers are susceptible to temptation like anyone else, despite taking their oath of attorney. It’s an old story, and the supernatural elements rob the material of subtext, even while giving Pacino ample room to showboat.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on May 3, 2023. Thanks for your patronage and continued support, Cooper!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review