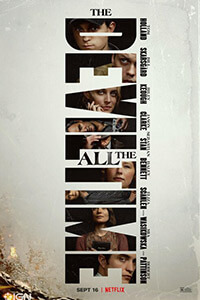

The Devil All the Time

By Brian Eggert |

A grim take on the banality of evil, The Devil All the Time looks at humanity and sees little else besides misguided beliefs, twisted impulses, and corrupted systems of power. It’s a miserablist’s dream. It’s also a steadily paced, quiet epic of pain, featuring a theme about those who use God to justify their actions and explain away their own terrible behavior. The film unfolds in a novelistic fashion, leaping back and forth in time to explain some important detail that clarifies some other plot element. Along the way, moments of merciless, callous violence result from the characters’ delusions: The Lord likes this, the Lord doesn’t like that, or the Lord is testing me. And for every lesson in human awfulness compelled by the warped interpretation of God’s will, there’s a talented actor behind the episode. The Devil All the Time is one of the best-cast films in recent memory. But all the talent and craft behind the picture cannot overcome the story’s overbearing unpleasantness, which is, frankly, exhausting. And this is coming from a card-carrying cynic.

Co-writer and director Antonio Campos adapts the 2011 novel by Donald Ray Pollock, and the viewer can feel his screenplay, written alongside his brother Paulo Campos, struggling to contain every detail. Running just under two hours and twenty minutes, the film contains a lot of plot and perhaps not enough time to bond with more than one or two characters. The story begins just after World War II, when Willard Russell, played by Bill Skarsgård, returns home with PTSD to his small Ohio town called Knockemstiff. Despite his nightmarish experiences overseas, he maintains war “wasn’t dat bad” and keeps a tough upper lip. Eventually, he finds God, whom he prays to out in the woods, kneeling at a makeshift crucifix erected by a log. When his wife (Haley Bennett) contracts cancer, Willard resorts to all manner of extremes to keep her alive, not the least of which is crucifying the family dog, the best friend to his 9-year-old son, Arvin (Michael Banks Repeta). But this is just one such passage in a film overrun with subplots about people who do horrible things to one another, usually in the name of a higher power.

Take the evangelical preacher named Roy (Harry Melling), whose act, rather than taming snakes, involves dumping a jar of poisonous spiders on his head to demonstrate that his piousness has earned the protection of God. When Roy is inevitably bitten (it tends to happen when pouring a jar of spiders on one’s head) and near death, he convinces himself that he has been imbued with holy powers. So he stabs his wife, Helen (Mia Wasikowska), with a screwdriver to prove that he can resurrect her. The Devil All the Time carries on this way for much of the runtime, one horrific story connecting to another. “There’s a lot of no-good sons-of-bitches out there,” says Willard to his son, a line that the older Arvin, now played by Tom Holland, repeats in the 1960s. And based on everything we see in the film, it’s a difficult point to argue against. Violence has passed from one generation to the next, and there’s not a pleasant minute in the whole damn film.

The story follows two intersecting storylines. One tracks the adult Arvin as he realizes his step-sister, Lenora (Eliza Scanlen), the orphaned daughter of Roy and Helen, has fallen victim to the sexual predations of the flashy new Reverend Preston Teagardin (Robert Pattinson, excellent). The other follows a couple, Sandy and Carl (Riley Keough and Jason Clarke), who perform serial murders before there was even a name for such things. The couple picks up wayward hitchhikers, always young men they call “models,” and then forces them to pose with Sandy for nude photos before Roy kills them. Given the sheer amount of screentime given to these perpendicular storylines, you just know both Sandy and Carl will eventually cross paths with Arvin. But even though the story plays out in predictable ways, the cast and directorial choices make The Devil All the Time continuously engaging, even though a major bummer remains unavoidable.

The story follows two intersecting storylines. One tracks the adult Arvin as he realizes his step-sister, Lenora (Eliza Scanlen), the orphaned daughter of Roy and Helen, has fallen victim to the sexual predations of the flashy new Reverend Preston Teagardin (Robert Pattinson, excellent). The other follows a couple, Sandy and Carl (Riley Keough and Jason Clarke), who perform serial murders before there was even a name for such things. The couple picks up wayward hitchhikers, always young men they call “models,” and then forces them to pose with Sandy for nude photos before Roy kills them. Given the sheer amount of screentime given to these perpendicular storylines, you just know both Sandy and Carl will eventually cross paths with Arvin. But even though the story plays out in predictable ways, the cast and directorial choices make The Devil All the Time continuously engaging, even though a major bummer remains unavoidable.

Shooting on actual film stock in various locations throughout Alabama—though the story takes place primarily in Ohio and West Virginia—cinematographer Lol Crawley gives the images a texture that makes them a joy to watch. The colors appear far from muted, but everything has a 1940s appearance, as though the downtrodden characters have dressed in last decade’s fashions. The sole exception is Pattinson’s Reverend Teagardin, who anticipates Elvis with his ruffled shirt and angel-white car with winglike tailfins no less. Elsewhere, the director makes several curious choices that reveal his overdependence on the novel. The persistent narration, performed by Pollock, turns The Devil All the Time into an unsatisfying blend of film and literature. Pollack’s voiceover often explains his characters’ motivations, breaking the somewhat overstated rule of show don’t tell. It’s not a rule that I always believe in; however, it would have been preferable here. Pollack’s commentary supplies the voice of an omniscient witness who seems to be from the area. He refers to the ill-fated Helen as “poor thing” and describes one character as smelling “worse than a truckstop shitter.”

Pollack’s narration and the omnipresent violence working its way through these characters become rather daunting and repetitive by halfway through The Devil All the Time. A dull pattern emerges: Whenever you get an inkling that a character might be murdered, commit a horrendous crime, or sexually assault someone, the chances are that’s exactly what will happen. Although the viewer might grow numb to this routine, the performances elevate the material. Holland is terrific as a young man grappling with the violent lessons his father passed down, whereas Pattinson disappears into his role as the creepy preacher. Scanlen and Wasikowska barely have enough screen time for their considerable talent. But by the end, you may wonder why you just endured this Southern Gothic tableau, which only superficially captures the events as they occur. The emotions and greater meaning might be locked inside Pollack’s novel, where his characters’ inner thoughts and feelings have room to maneuver and bloom. Campos seems so concerned with portraying major events from the book that he forgets to adapt the material for the screen, leaving it to feel rather punishing and lifeless in a superficial way.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review